Japanese writer Jun Ishikawa faced censorship under two different regimes.

In the 1930s, the nationalist Japanese government fined him for publishing a story that criticized militarism. A decade later, U.S. forces occupying the country told him to remove parts of a short story depicting an American soldier fraternizing with a Japanese woman, rendering the story nonsensical.

In other words, censorship was a “trans-war phenomenon in Japan,” said Visiting Assistant Professor of Japanese Helen Weetman.

Weetman presented on censorship pre- and post-World War II Japan on Wednesday as part of Banned Books Week, a national campaign to protest censorship and promote the freedom to read. To mark the week, Bates Ladd Library held a series of presentations on censorship outside the United States in the 20th century.

It was a departure from last year’s series, which explored censorship in the United States and locally. Focusing on censorship around the world allowed the Bates community to consider a broader range of reasons why governments, organizations, and individuals try to prevent books from being published or read.

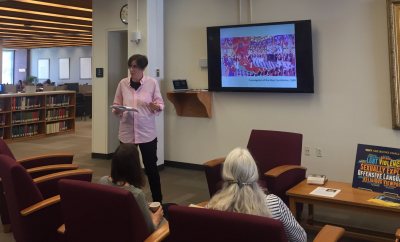

Stephanie Pridgeon, visiting assistant professor of Spanish, presents on censorship in Argentina in the 1970s and 80’s as part of Banned Books Week. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

“In the United States, it’s much more about sex and religion, and in other countries it has more to do with politics,” Juraska said. “It’s an interesting difference of what tends to get banned where. It tells you something about the culture that we live in.”

In Germany in the 1930s, the initiative to suppress certain books came not from the Nazi government but from student organizations, said Assistant Professor of German Jakub Kazecki. Students led the charge to collect and burn books by authors with an “un-German spirit,” many of whom were Jewish.

Book-burnings took place around the country on May 10, 1933. In Berlin, the students were encouraged by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

Assistant Professor of German Jakub Kazecki presents on book-burning in Nazi Germany on Sept. 28 as part of Banned Books Week (Emily McConville/Bates College)

“What always gets me when I look at the photographs of this event is the happy, smiling faces of the students,” Kazecki said. “They were so happy to participate in this event.”

In Argentina in the 1970s and 80’s, censorship also helped a military junta maintain power, said Visiting Assistant Professor of Spanish Stephanie Pridgeon.

Book burnings were also common there: At one point, in a quest to eradicate books that were not in keeping with nationalism and Catholicism, the regime collected and burned 1.5 million books from a single publisher, Pridgeon said. People suspected of subversion would often come home to find their bookshelves ransacked.

“At the same time books were being burned, they were also used as evidence of political activists’ subversion,” she said.

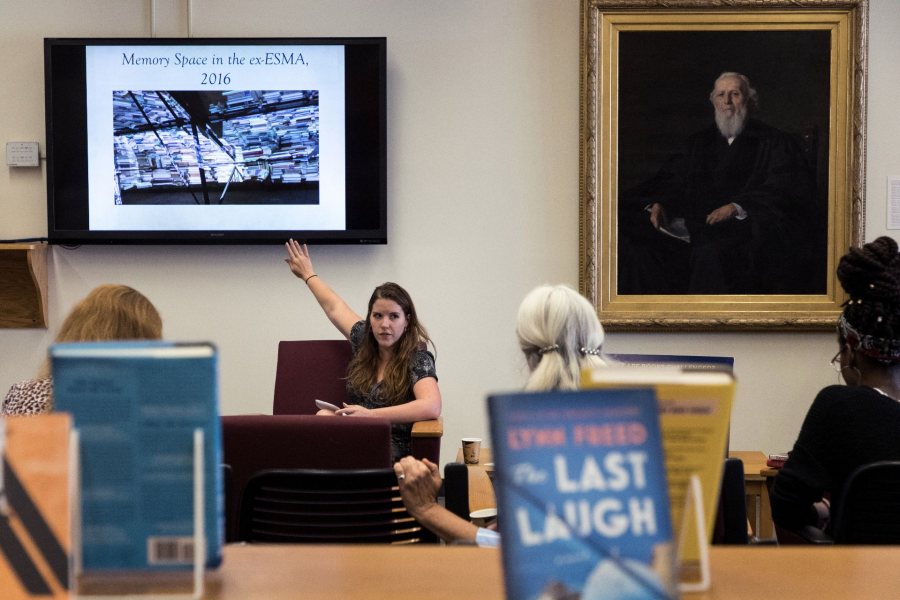

In Japan, in addition to censoring Ishikawa, the U.S. occupation government after World War II cracked down on materials that promoted militarism and nationalism, going so far as to have children black out parts of their textbooks with heavy ink, Weetman said.

Then, as Japanese political discourse tipped to the left, the occupation government began to censor suspected Communists, socialists, and unionists as well.

The censors were trying to suppress not only views the U.S. considered unfavorable, but also the existence of censorship itself.

“It’s essential that you make no reference to the fact that censorship is occurring, so you cannot refer to censorship,” Weetman said. “You also cannot largely refer to the occupation itself. It’s not that nobody does, but it’s discouraged.”

Visiting Assistant Professor of Japanese Helen Weetman discusses the history of censorship in Japan during Banned Books Week. (Emily McConville/Bates College)

The totalitarian regimes in Argentina, Germany, and Japan eventually fell, the U.S. occupation of Japan ended, and — as within the United States — censorship became less severe in the later 20th century. Each country is reckoning with its past, and censorship, or the memory of it, is a factor in those reckonings.

Pridgeon said one former detention center in Argentina, now a museum and memory center, projects images of confiscated books on its walls — an expression of memory that is still fraught.

“The superimposition of this image comes as part of a broader movement that is deliberately seeking to re-insert politics and ideology into what had previously been presented as an ostensibly depoliticized space of human rights and memory,” she said.

Many book-burning sites in Germany have also become spaces of commemoration, Kazecki said.

At the location of the infamous 1933 book burning in Berlin, a plate of glass allows passersby to look underground into a set of empty bookshelves, enough to hold the books that were burned. On May 10 of each year, a man in Munich blowtorches the grass over a spot where books were burned — “I think it is necessary to remember without covering history with grass,” he has said.

On many of the plaques marking book burnings throughout the country, there is a quote from Heinrich Heine, a 19th-century writer who protested a symbolic book-burning in 1817: “Where they burn books, they will in the end also burn people.”

A final presentation on LGBT and religious themes in international censorship by Visiting Assistant Professor of English Tiffany Slater will take place on Oct. 2.