Though her school had a rule against using cellphones during class, a teacher allowed a student to use his phone to show her something lesson-related.

Another teacher permitted students to record homework assignments on their phones.

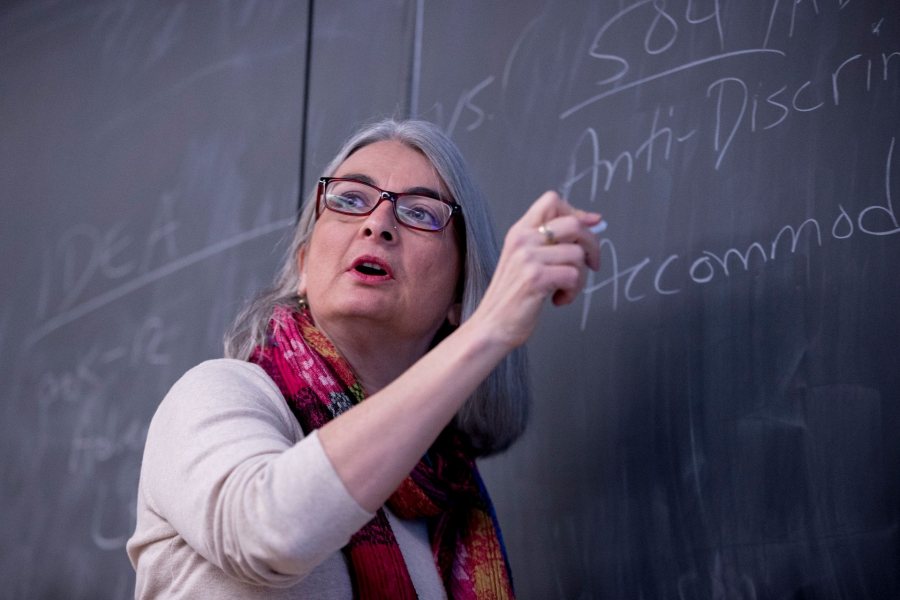

While the public often hears about “no phone” edicts in schools, the reality of cellphone use in schools tends to change from teacher to teacher and even from day to day, says Anita Charles, a lecturer in education at Bates who studies literacy and special education and who directs the college’s teacher education program for secondary teacher candidates.

In fact, says Charles, cellphones get at “the heart of rule-building” in the classroom: The best rules are built on trust and respect, and that respect is a two-way street.

Since 2008, Charles has been part of the scholarly discussion about cellphone use in schools. That year, she observed classrooms and interviewed high school students and English teachers for a paper that was published in the journal American Secondary Education in 2012.

In 2017, she contributed a chapter to Researching New Literacies: Design, Theory, and Data in Sociocultural Investigation, offering insights into technology in the classroom and the nature of trust between students and teachers.

What did you learn from interviewing students and teachers about rules about cellphones and enforceability?

I found that when schools attempted a blanket policy, invariably, it was unenforceable. Teachers and students developed work-arounds.

What I found, without people explicitly stating it, or even knowing that they were doing it, was that managing cellphone use was really about contextualized negotiation, happening classroom by classroom, teacher by teacher, group by group. Overwhelmingly, I found that standards around cellphone use were founded on how students and teachers were building relationships with each other.

Even when teachers said, “I have this rule,” there was always the “but.” “I have this rule, BUT then again there are these times…” or, “Well there was a day when….” Even a teacher who was working in a school which did not allow any of these items in the classroom said, “I’m the teacher they can come to if they need to call their mom or if they need to jot down their homework. I don’t care.” She said, “I just think it’s reasonable to do that.”

Overwhelmingly, the students recognized when teachers were working with them to develop a reasonable policy. When they knew that teachers were developing policies that made sense, they also were much more likely to respect and honor those policies.

Your initial interviews were a decade ago. How have cellphones and their roles in classrooms changed in the decade since?

Our technology is getting smarter and smarter, more intuitive, more sophisticated, more versatile, and also more prolific. It used to be easy enough to say, “Put away your cellphone,” when the only thing it did was make a phone call or text.

But now, it’s also your calendar, it may be your note-taker, you may be taking a picture of the board to get your homework assignments, it may be recording something you need. And there may be kids with differences or disabilities who prefer using these tools as a way to access schoolwork. Teachers also have their own devices in their hands.

We’re not turning back time, so we have to come up with a sensible way to say, “How do we engage with this in schools, and how do we develop rules?” Not even how do we develop rules, but how do we talk about reasonable guidelines?

What might a reasonable guideline be?

It’s not an all-or-nothing kind of thing. I think we need to have conversations. We can say to kids, “Have you thought about the pros and cons? How does a device work in your own life? How much time are you spending on your devices? What kind of time are you spending on them? What’s happening when you’re feeling that urge to get on it in the classroom?”

Students can articulate reasons, and I think we need to honor that and listen to that. I’d ask the participants in my study, “Are you texting in a classroom?” “Well, I’ll text in English, but not in math.” “Why?” “Well, in math, I have to pay attention more.” Or, “I never text in this particular class, because the teacher engages me, and I want to be learning.”

In my own Bates classes, I’ll start by saying that laptops and phones or devices may be used during class at their discretion, for class-related purposes. That gives a fair shot for people to be mature about the way in which they’re using them. It also allows for the fact that there are class-related purposes.

I don’t think we should shut down those processes, and it’s not for me to micromanage them either. I should not have to rotate through the back of the room and say, “Are those notes for this class? Are you enlarging that on your screen because you can’t see?” That’s not my business. I think we need to let go of our control a little bit.

What do you say to Bates students studying to be teachers about technology in the classroom?

I do observations with my student teachers who are placed in middle and high schools. One of the things I look for while scanning around the room is if any of those students are on devices.

Quite often, somebody does have one out, and they’re doing something quick with it. I then have a conversation with my student teacher: “Did you see it? What do you think about that? Is this becoming problematic?” I ask, “How are you thinking about this issue in your classroom?”

There’s something in teaching called “with-it-ness” and that can’t really be taught. It can be encouraged, but it can’t be taught. With-it-ness is having eyes in the back of your head, being aware of who has phones out. It’s positioning yourself in the classroom so you can do a scan. I think I’ve seen some pretty reasonable approaches with my student teachers who might say gently, “Put that away now,” or they go nearer to the student, tap on their desk, maybe give a reminder: “If I have to ask again, I’ll need to take it.”

You can’t become a monster in the classroom any more than you can for any other rule-breaking — and there are lots of ways that we can break rules. So what do we do? We gently redirect, we acknowledge it, we help students self-monitor. Self-monitoring is ultimately going to be a lot more successful than top-down monitoring.

It seems that managing cellphone use is more about relationships and trust.

The heart of rule-building in schools is about relationships. I’m not comfortable with someone saying, “What would you come up with for a rule?” We need to ask, “What’s the scenario?” and, “Let me talk with people, and let’s figure out what’s happening.”

In classrooms, we hear a lot about respect: Everyone needs to respect each other. But we don’t really talk about what that looks like or means. We’re all just supposed to know what respect is. Meanwhile, we can say that we believe in respect, but we also say, “Don’t touch your phones because I don’t trust you with them.” My take on that is that our actions certainly speak louder than words. If I say, “Let’s work through what we can all live with in terms of cellphone use in the classrooms,” that relationship helps us negotiate out what’s okay and what isn’t okay.

And if we respect, trust, like, and support each other, then we are engaging in an agreement. We can explicitly articulate some of that agreement. We could even have it up on the walls and all sign off on it. But some of it happens when we engage with each other. When a student asks if they can take a photo of the board so they have the homework assignment, then that might become a new protocol in the classroom. I think that’s a reasonable protocol.

And if someone abuses the trust then you can deal with it as an abuse of trust, not necessarily something specific to cellphones.

Right, just like any situation where somebody abuses trust. If I have a rule about food in the classroom and somebody decides to throw food all over the place, they’ve abused that trust. So we have to renegotiate, or we have to tighten up the reins or say, “Gosh, that really disappoints me.” If we’re in relationships, that sense of disappointment speaks more loudly than a hard and fast rule.

People can abuse any privilege, like driving a car or having a pen or pencil in your hand. We have to work with those cases as, “Gee, I was trusting you, and we were building a rapport, and you have really not abided by that expectation, and what do we do next?” That’s the way we should handle any of these things.

Teenagers have an uncanny sense of fairness and what’s reasonable. They appreciate being treated as young adults, but they also appreciate boundaries — they don’t actually want a free-for-all. Negotiation, when they feel that they’re being listened to, benefits everybody, because the teacher finds that students become more cooperative.

If we approach cellphone use as negotiating a relationship, it’s not all subversive. It’s not all under the current somewhere. It’s not kids sneaking out to the bathroom to use their phone.