Bates debates Harvard at City Hall

February 1920: Bates debates Harvard at City Hall

Like an up-and-coming prizefighter, Bates debate in the early 20th century craved a shot at the best. In 1920, that meant a match versus Harvard, “the mecca of Bates’ debating hopes,” in the words of the Mirror. Weary of beating up on “institutions inferior to her standard,” Bates finally lured Harvard to Lewiston in February 1920. The debate was set for Lewiston’s City Hall, and though enjoying home-field advantage, Bates otherwise had to accept “onerous” conditions.

The Crimson, debating for only the second time outside its traditional “triangular” competition of Princeton and Yale, got to choose the topic (whether the federal government should take ownership of the railroads), the side (negative, which Harvard had already successfully argued versus Dartmouth) and an early date (Feb. 23, giving Bates just three weeks to prepare).

Bates was also handicapped by coach Craig Baird’s bout with the flu in the days leading up to the match. Professor of Economics John Carroll ’09 stepped in to help, as did Debating Council president Benjamin Mays ’20, who had “a large corps of assistants at work, and promise[d] that not a detail will be lacking to make the ‘scrap’ a success.”

Signaling the match’s significance for both Bates and the state, Maine Gov. Carl E. Milliken, Class of 1897, agreed to preside. “The Governor is giving up important engagements to be at the debate,” noted The Bates Student of Feb. 20, 1920, “sufficient proof that alumni are watching the affair.” Following selections from the Bates orchestra, a prayer from an Episcopal priest and cheers for both teams ending with “the old Bates yell,” the debate commenced before an audience of 1,000.

The full debate topic was “Resolved: That the United States should adopt the Plumb Plan for the operation of its railroads, as embodied in the Sims Bill (constitutionality waived).” This was 50 years before the example of Amtrak, but even in 1920 supporting federal ownership was considered the weaker proposition.

So while Bates set out to prove that federal ownership would be more efficient and less costly than private ownership, Harvard, in its rebuttals, tried to demonize the notion of government ownership. “Only 11 times during his presentation did [Harvard] call the Plumb Plan a revolutionistic, a drastic, a socialist, a dangerous, a pernicious plan which would be found nowhere unless in lowest Russia,” noted the Student.

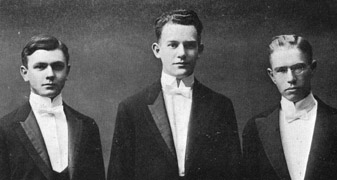

Yet the Bates team of Charles Starbird ’21, Robert Watts ’22 and Arthur Lucas ’20 was unflustered. Arguing the affirmative, they’d just beaten Cornell a few weeks prior in a question over whether the federal government should require “the Shop Committee System,” that is, a method for workers to organize themselves within a company, in larger U.S. industries.

The Student lavished high praise on Robert Watts, the third affirmative and final rebuttalist, for stripping the negative “of their camouflage coat of oratory and [laying] bare the straight facts.” Watts’ passion perhaps foreshadowed a career: He would earn an honorary degree from Bates in 1957 for his work in another transportation field, as counsel to General Dynamics’ aerospace division, Convair.

Another musical interlude preceded a unanimous decision for Bates by the three judges, two from the Bowdoin faculty and one from the Supreme Judicial Court of Maine. “The Harvard men were polished speakers,” noted the Student in its post-debate story. “But they could not come up to the Bates speakers either in delivery or subject matter.”

The victory was followed by another win over Harvard, at Cambridge, and over Yale at New Haven. In 1921, Bates held the first intercontinental debate, against Oxford. By 1922, The New York Times would proclaim Bates “the power centre of college debating in America.”