‘We got you. We got each other:’ Words of encouragement to the Class of 2020, from a millennial professor

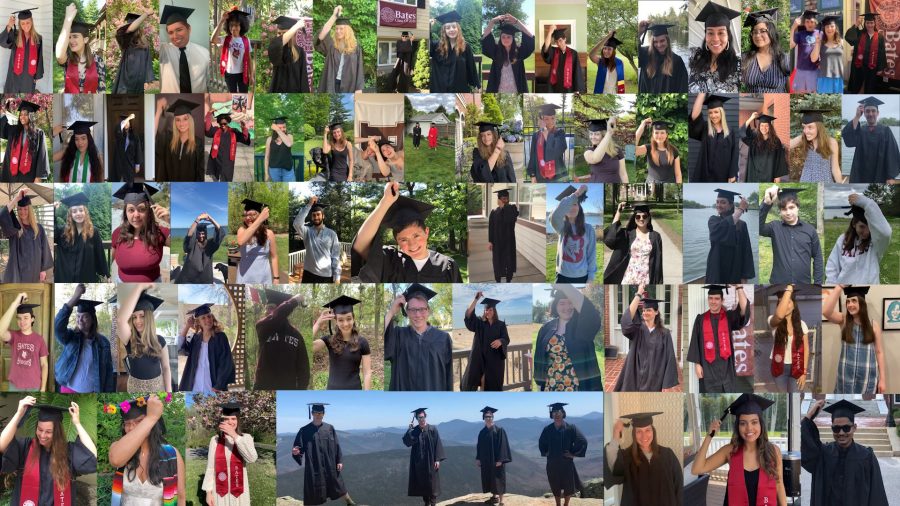

As some of you post videos of yourself walking across the camera in your regalia or have low key offline celebrations or participate in online shindigs, consider me one of your millennial sisters cheering you on. We are so excited for you. We remember clearly how it felt to graduate both high school and college: that breeze of completion, the smell of freedom, the disappearance of certain burdens.

Some of you entered school in 2016. Feeling the strange twinge of both pessimism and hope, you kept on. Again, you find yourselves in an unprecedented moment. Rightly so, folks are telling you that history has caught you, and that you have the opportunity to author your futures. They’ve talked about your contributions during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. They’ve told you that we’re still in the early days. Facts.

As a Black college professor of English and African American Studies (and a millennial), I want to tell you what I think might be an oddly comforting thought. You’re not unique. I know that flies in the face of much of what you’re hearing. True: a pandemic of this sort has not been seen since 1918 and the effects of it have been exacerbated by a globalizing world. Obviously, we’re not facing something easy. But, you’re not the first ones to face times of flagrant uncertainty. Some of us are still living. Some of us are not that much older than you.

Millennials get you. We will have lived through two recessions. We watched hope and change careen into hate and chaos. We saw the upsurge of the ugly underbelly of a nation. We watched the powder keg build up — racism, misogyny, ableism, classism, transphobia, homophobia — and then we saw COVID-19 help set it aflame. That disintegrated hope? We had it. Those shattered dreams? We’ve got those. That workforce? We’re in it. That debt to pay? We’re anxiously holding our chip cards, too. There’s the good news in not being unique. You’re not alone.

I spend most of my time reading and teaching Black novels: Danzy Senna’s collection of short fiction You Are Free, Alice Randall’s exploration of the inner life of a Black conservative Rebel Yell, Octavia E. Butler’s dystopian science fiction (all of it). The list continues. Each of the authors I mentioned before along with many others spend their time thinking of one character — sure — but that character is forged in the crucible of a community. Their foibles, their triumphs can certainly be called their own, but they are not going at it alone. And, when they try, the consequences of being alone usually include getting caught up, feeling bereft, and having a warped understanding of one’s place in history by either overstating or underselling. One of the abiding concerns of Black literature is its emphasis on how community works and when it fails. The tradition is suspicious of naked individualism. As it should be.

Therí Pickens

Therí A. Pickens is a professor of English at Bates. A specialist in African American, Arab American, and disability literatures and theories, she is the author two books, including the recently published Black Madness :: Mad Blackness (Duke University Press, 2019). This essay was originally published on Medium.

Take Alice Walker’s classic, The Color Purple. Celie’s journey to fully realize herself is not just about her marriage to Mr. ____ or her relationship with Shug Avery or her longing for her sister. She is a Black woman in the rural South who ekes out a space for herself among a community of relatives. Along the way, the community has to bend and change to create space for new members, new ideas, new circumstances. See? I told you that you weren’t alone.

By the novel’s end, Celie and the cast of characters understand each other, perhaps uneasily. (They don’t actually stand around watching Celie and Nettie hug like they do in the movie.) Some problems linger there, like ghosts. Here’s the thing: anyone who has read an Alice Walker novel knows that her books are gems for their humor, wit, and their clarity about one’s inner life. There’s joy in the telling.

I bet that is one word you didn’t expect to hear: joy. But, isn’t that the point of telling you that you’re not alone? If you look back on these past few months, you can remember the endless days inside, the fear about toilet paper, the frustration regarding leadership, but you should also remember the times you laughed, the times you found some hope. It isn’t a cliché to say you had a moment of being elated. It happens. No need to stand at an ironic distance and feel superior to those who found a silver lining. And, if you didn’t have one, know you’re not alone either. Even in the darkness, there’s hope in community as well.

But Wait! you say, not all Black literature has hope as its underlying theme. Good for you English and African American Studies majors. Your degree is already paying dividends. You’re right. Each story does not have hope or joy as its center, its foundation, or its end-game.

But, that’s not really the point.

The point is that you’re not alone.

One of the major components of Black literature is its intergenerational wisdom. It is how I, as a millennial, can tell you, Generation Z, that we’ve got this. Because I know what Gen X and the Boomers told me. You’re not alone. You’re not quite unique. We’ve seen these things before.

We been knowing.

We got you.

We got each other.