News from the Harward Center for Community Partnerships – Summer 2017

In This Issue

- Building Faculty Capacity: The 2016 Publicly-Engaged Pedagogy Learning Community

- Student Voices: Short Term Action/Research Team

- Faculty Spotlight: Professor Bev Johnson

- Student Voices: Community-Engaged Research Fellows

- Faculty Spotlight: Professor Mara Tieken

- In The News

Dear Friends,

Summer greetings from Maine! I am delighted to share the Harward Center’s biannual newsletter, which offers a window onto some of the exciting publicly-engaged work happening at Bates College in recent months. This edition of the newsletter highlights student and faculty voices, a new faculty development initiative, and a range of compelling questions and topics. You’ll hear from two distinguished faculty members, including the 2016 winner of the nationally competitive Ernest A. Lynton Award for the Scholarship of Engagement for Early Career Faculty, and four fantastic students. There are many additional stories we could share. . . If you want to know more, please be in touch, and feel free to share the newsletter far and wide.

With appreciation for your interest and support,

Darby Ray

Harward Center Director

Donald W. and Ann M. Harward Professor of Civic Engagement

Building Faculty Capacity: The 2016 Publicly-Engaged Pedagogy Learning Community

Did you know that in a typical year at Bates, around 800 students take at least one community-engaged learning (CEL) course? Almost every academic department and program offers one or more CEL course. However, developing a CEL course takes time, expertise, and strong working relationships with prospective community partners. How can busy faculty members fit such things in while maintaining their commitment to excellence in the classroom and their discipline? We might assume that the prudent course of action would be to earn tenure before venturing into the sometimes unpredictable waters of community-engaged teaching, but a strong argument can be made that the ideal time to integrate CEL into a course is during the initial phase of course design and implementation. At Bates, where the Harward Center provides comprehensive support for CEL, increasing numbers of pre-tenure faculty are successfully integrating community-engaged work into their courses, producing enhanced learning experiences for students, positive benefit for community partners, and gratifying teaching experiences for faculty.

One new avenue of support for both pre-tenure and tenured faculty is the Publicly-Engaged Pedagogy (PEP!) Learning Community, which saw a successful launch during the fall semester of 2016 and whose fruits were abundantly evident during the subsequent winter and spring terms. The PEP Learning Community was open to all interested faculty members, with an emphasis on pre-tenure faculty. Originally designed for a cohort of six faculty, the program was expanded to ten to meet faculty demand from across the disciplines. Those ten faculty members met together once a month during the fall semester — joined by Harward Center staff members and buoyed by dinner from a local restaurant — to develop a new community-engaged learning course. Attention was paid to diverse topics and tasks, including student learning outcomes, syllabus language, course assignments, community engagement ethics, logistics like transportation, and the all-important question of community reciprocity and benefit. In addition to the monthly cohort gatherings, PEP faculty had one-on-one consultations with Harward Center staff to support their course design and partnership building.

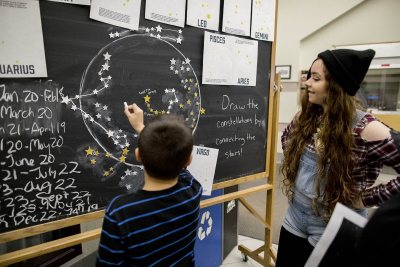

As a result of the PEP Learning Community, six new community-engaged learning courses were taught for the first time during the subsequent winter and spring terms. These courses featured diverse community-engaged projects in Politics, Environmental Studies, Dance, Religious Studies, Physics and Astronomy, and Biology. For example, in a Religious Studies course on Death, Dying, and Afterlife, professor Alison Melnick’s students complemented their learning about Asian religious traditions with class visits from local leaders of Western traditions such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. At the end of the semester, these leaders and others from their congregations joined the Bates students for a Community Teach-In. The Teach-In featured interactive poster presentations by Bates students to convey their learning about Asian traditions, followed by a dessert reception and small-group discussions, facilitated by Bates students, during which members of the different Western religious traditions were invited to share insights and practices from their own traditions while learning about traditions different than their own. In a large introductory course in Astronomy, professor Aleks Diamond-Stanic gave his students the option of doing a community-engaged project, and 77 out of 83 of them jumped at the chance, working together to produce a wildly successful “Astronomy Extravaganza” for local school children and their families. In Biology, professor Andrew Mountcastle challenged students in his Science Communication course to develop skits and interactive presentations to engage Lewiston Middle School students in learning about contemporary issues is science. The middle schoolers came to Bates on two different days to enjoy creative and compelling lessons about a range of topics from ocean acidification (featuring a memorable Nemo skit) to bee colony collapse (with an audience-participation activity featuring Queen Bey). At the end of each presentation, middle school students took a moment to jot down their learning and questions, and these reflections eventually formed the basis for small-group discussion with Bates students over lunch. In Literatures of Agriculture, professor Misty Beck’s students enjoyed a range of community-engaged experiences, including volunteer placements at Whiting Farm in Auburn, the Somali Bantu Community Association, and the New Roots Cooperative farm. Based on these immersive experiences, students created written and photographic portraits of their experiences with agriculture, some of which they shared at the end of the semester when they visited an active Grange Hall in Vassalboro, where they learned about the traditions of the grange and shared their findings about the trends and developments they observed in their fieldwork. In professor Jacob Longaker’s Experiences in Policy Process course, students complemented classroom learning about the behind-the-scenes negotiations, maneuvering, and strategy that shape policy by engaging in hands-on work with community partners advancing legislative initiatives at the state level. Some of the projects were primarily research-based, with students collecting information to help with education and advocacy efforts; other projects were more advocacy focused, with students communicating directly with members of the voting public about specific issues. Partners included the Maine Prisoner’s Advocacy Coalition, the Prevent Harm environmental advocacy group, the Maine People’s Alliance, Equality Maine, and the American Cancer Association.

Andrew Mountcastle challenged students in his Science Communication course to develop skits and interactive presentations to engage Lewiston Middle School students in learning about contemporary issues is science. The middle schoolers came to Bates on two different days to enjoy creative and compelling lessons about a range of topics from ocean acidification (featuring a memorable Nemo skit) to bee colony collapse (with an audience-participation activity featuring Queen Bey). At the end of each presentation, middle school students took a moment to jot down their learning and questions, and these reflections eventually formed the basis for small-group discussion with Bates students over lunch. In Literatures of Agriculture, professor Misty Beck’s students enjoyed a range of community-engaged experiences, including volunteer placements at Whiting Farm in Auburn, the Somali Bantu Community Association, and the New Roots Cooperative farm. Based on these immersive experiences, students created written and photographic portraits of their experiences with agriculture, some of which they shared at the end of the semester when they visited an active Grange Hall in Vassalboro, where they learned about the traditions of the grange and shared their findings about the trends and developments they observed in their fieldwork. In professor Jacob Longaker’s Experiences in Policy Process course, students complemented classroom learning about the behind-the-scenes negotiations, maneuvering, and strategy that shape policy by engaging in hands-on work with community partners advancing legislative initiatives at the state level. Some of the projects were primarily research-based, with students collecting information to help with education and advocacy efforts; other projects were more advocacy focused, with students communicating directly with members of the voting public about specific issues. Partners included the Maine Prisoner’s Advocacy Coalition, the Prevent Harm environmental advocacy group, the Maine People’s Alliance, Equality Maine, and the American Cancer Association.

“This has been the richest teaching experience I’ve had in 25 years. Truly. Straight up.” Such was the testimony of one of the PEP faculty participants who reflected on this first foray into community-engaged teaching. While there were certainly bumps along the way, the inaugural PEP cohort members were unanimous in their appreciation for the opportunity to journey with each other, with Harward Center staff, and with their students and community partners into the land of publicly-engaged pedagogy. Feedback from students and partners was equally positive (perhaps a story for another day).

Student Voices: Short Term Action/Research Team

Spring time at Bates means, among other things, the Harward Center’s Short Term Action/Research Team (START). This year’s program featured ten students, each of whom worked twenty hours per week during the five-week Short Term to complete a project for a local nonprofit or social entrepreneur partner. Community partners included Healthy Androscoggin, Museum L-A, the Immigrant and Refugee Integration and Policy Development Working Group, Tri-County Mental Health, Montello Elementary School, Health Equity Alliance, and Lewiston Middle School. Two other partnerships are described below by START participants Sean Antonuccio (Economics major) and Emily Halford (Biology and Environmental Studies double major).

Sean Antonuccio

I first met Amy Smith, the founder and director of Healthy Homeworks, at the START kickoff organized by the Harward Center in late March. After speaking with her for nearly an hour, I had a good sense of the inner workings of Healthy Homeworks. In short, Healthy Homeworks is a non-profit agency that aims to provide suitable sleeping arrangements to those without them. The cornerstone initiative is the Earn-a-Bed program, which offers a bed (frame, bed cover, and mattress included) to those with an inadequate sleeping situation in exchange for 20 hours of volunteer work. During those 20 hours, the volunteer builds not only their own bed, but two to three other beds as well. Amy then tries to sell this surplus, either wholesale or retail, in hopes of subsidizing the program’s cost. You can read more about the program in this recent Portland Press Herald story.

I first met Amy Smith, the founder and director of Healthy Homeworks, at the START kickoff organized by the Harward Center in late March. After speaking with her for nearly an hour, I had a good sense of the inner workings of Healthy Homeworks. In short, Healthy Homeworks is a non-profit agency that aims to provide suitable sleeping arrangements to those without them. The cornerstone initiative is the Earn-a-Bed program, which offers a bed (frame, bed cover, and mattress included) to those with an inadequate sleeping situation in exchange for 20 hours of volunteer work. During those 20 hours, the volunteer builds not only their own bed, but two to three other beds as well. Amy then tries to sell this surplus, either wholesale or retail, in hopes of subsidizing the program’s cost. You can read more about the program in this recent Portland Press Herald story.

During my five weeks as a START Fellow, I could be found making profitability excel sheets or on my hands and knees sanding down bed posts. At the moment, Healthy Homeworks relies on grants to stay afloat; however, Amy hopes the non-profit will be self-sustainable in the next three to five years. To accomplish this, she “simply” has to sell more beds. Thus, a good deal of my time was spent making profitability and forecasting tools, as well as figuring out the logistics of shipping the 100+ pound bed frames made of Maine lumber. On my final day, Amy and I shipped our first bed frame (in a container made out of old bicycle boxes that were jury-rigged) to South Carolina. I later learned the frame arrived safe and sound.

As an Economics major with scant volunteer experience, I was originally primarily interested in the business side of Healthy Homeworks. Well, at least at first. It was hard not to notice how passionate Amy is about her agency’s social mission and her hope to help improve Lewiston. Numerous times I would come in at 9:00 am to later find out Amy had been there since 4:00 am. Amy’s passion, in addition to my interactions with countless volunteers, made this a truly worthwhile experience.

Emily Halford

My START project was to explore the feasibility of implementing a health coaching program that would link Bates College students and local healthcare providers. The term “health coaching program” refers to a program where trained students provide non-clinical supportive care to patients identified by a partner hospital, assisted living facility, or health clinic. This supportive care can take a variety of forms, but it most commonly entails either connecting patients with the resources they need to maximize health or coaching patients through the lifestyle changes necessary to confront certain common chronic diseases.

Health coaching programs are beneficial because they offer the opportunity for students to gain valuable healthcare experience while confronting major issues like poor health literacy, high hospital readmission rates, and social determinants of health. A handful of undergraduate schools have successfully implemented such programs, and it appears there might be a place for a program of this sort at Bates and in the Lewiston community. This uncommon program would set Bates apart from other similar schools for any student interested in the health sciences, and in turn would set participating students apart in graduate school application pools.

I have spent the past few weeks exploring the challenges and considerations entailed in starting a health coaching program at Bates, and although there are many factors to take into account, something along these lines might be feasible. If further exploration into this idea is undertaken, Bates and its healthcare partner would need to consider numerous issues, including methods of training students, the kinds of patients to target, liability and student safety, funding, staffing, and transportation. However, all of these considerations are manageable. Most importantly, a health coaching program at Bates would help maximize the community’s health while filling the gap created by diminishing shadowing and clinical experience opportunities for pre-health students.

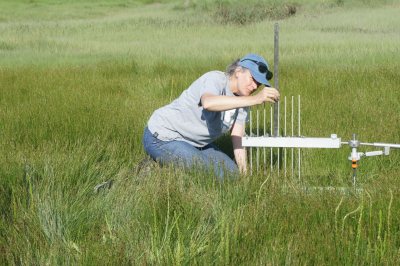

Faculty Spotlight: Professor Bev Johnson

A recent Portland Press Herald article featured Geology professor Bev Johnson for her efforts to identify large and invisible influences on climate. The article is perfectly titled: “At Bates-Morse Mountain, there is a lot more going on than sun-bathing: Students and professors dig in deep for lessons on climate change.”

The lessons are mostly buried below the surface and hidden as “blue carbon”—referring to the carbon that is sequestered and stored in coastal wetlands, or salt marshes, seagrass meadows, and mangroves. Johnson and her students began their research on blue carbon by developing a clever method for estimating how much carbon is stored in the Sprague Marsh, at Bates-Morse Mountain. Working with Margaret Pickoff ’13, Johnson mapped the underground depth or topography of the peat layer of the marsh, and then analyzed the carbon density of the peat they pulled up in core samples. By adding up volumes and densities, early estimates suggested that the Sprague Marsh sequesters and then stores something on the order of what 30,000 cars emit in a year’s time. More recent calculations have honed the number to 900 metric tons per year. The method was included in a manual developed by the international group, The Blue Carbon Initiative in 2014, and has since been reported on at regional, national, and international conferences, and in additional publications. This early work on blue carbon sets the stage for evaluating carbon storage as a quantifiable ecosystem service, providing opportunities for carbon offsets and carbon markets. This, of course, adds to an already compelling case for the conservation of coastal wetlands.

Johnson’s work is clearly notable not just for its determination to identify significant factors in the global carbon equation. The work is additionally notable for its seamless stretch between pure science and critically relevant applications to a global-scale problem—the problem of climate change.

And furthermore, Johnson has not rested on laurels or concluded her research with carbon. In Johnson’s most recent work, she and students have studied salt marsh conditions that amplify methane emissions, or conversely, support the underground and natural storage capacity of salt marshes. For starters, they have confirmed earlier findings that more saline systems, meaning those that are open to the natural tidal flow (or not limited by tidal restrictions), provide the very best conditions for keeping methane in the ground. Again, the take home, “deep dig” lesson is that coastal conservation matters a great deal—for the sake of all planetary life. For that, we can thank Johnson and her students for their good science.

And furthermore, Johnson has not rested on laurels or concluded her research with carbon. In Johnson’s most recent work, she and students have studied salt marsh conditions that amplify methane emissions, or conversely, support the underground and natural storage capacity of salt marshes. For starters, they have confirmed earlier findings that more saline systems, meaning those that are open to the natural tidal flow (or not limited by tidal restrictions), provide the very best conditions for keeping methane in the ground. Again, the take home, “deep dig” lesson is that coastal conservation matters a great deal—for the sake of all planetary life. For that, we can thank Johnson and her students for their good science.

In coursework, Prof. Johnson has asked her students to identify effective ways to communicate climate science. Johnson’s Global Change course had students focus on the impact of climate change on different areas of the environment. As part of the course, Johnson asked students to put together information sheets for policy makers, distilling the science they had learned into language the general public could understand. She invited Bates alumna and freelance science journalist Laura Poppick into class to give students professional advice on the first draft of their information sheets. At the end of the course, students shared their fact sheets with and made presentations to former Maine state legislator and Harward Center staff member, Peggy Rotundo, who gave tips on how to advocate effectively for policy change.

Student Voices: Community-Engaged Research Fellows

During Winter Term each year, the Harward Center welcomes a small but talented group of students as Community-Engaged Research Fellows. These are students from a range of disciplines who develop a community of shared inquiry and support as they pursue diverse research projects in partnership with off-campus community members and with guidance from Harward Center staff members and faculty advisors. In this section, two of this year’s CER Fellows, Katie Stevenson and Isobel Curtis, share their community-engaged research stories. In addition, here is a link to a brief radio interview featuring Katie and her work. A third CER Fellow, Claire Brown, is featured in this BatesNews story.

Katie Stevenson

Walking through downtown Auburn, few notice the large, nondescript grey building hidden between the County Courthouse and the Auburn YMCA. This building is the Androscoggin County Jail. On any given night, over 70% of the individuals incarcerated there suffer from a substance use disorder and/or another mental illness. Like other correctional facilities across the country, the patients (traditionally referred to as inmates) at ACJ are often trapped in cycles of poverty, incarceration, and mental illness. In Androscoggin County, these cycles are exacerbated by public policy changes that lead correctional facilities, rather than mental health agencies, to act as the default mental health “treatment” facility in the county, a trend that has been seen nationally. I worked with Androscoggin County Jail (ACJ), in partnership with Tri County Mental Health Services, for my senior thesis, through which I became connected with the Harward Center’s Community-Engaged Research Fellows program. My research focused on quantifying the prevalence of mental illness among inmates at the jail and analyzing those prevalence rates within the context of recent changes in MaineCare and other public policies.

Walking through downtown Auburn, few notice the large, nondescript grey building hidden between the County Courthouse and the Auburn YMCA. This building is the Androscoggin County Jail. On any given night, over 70% of the individuals incarcerated there suffer from a substance use disorder and/or another mental illness. Like other correctional facilities across the country, the patients (traditionally referred to as inmates) at ACJ are often trapped in cycles of poverty, incarceration, and mental illness. In Androscoggin County, these cycles are exacerbated by public policy changes that lead correctional facilities, rather than mental health agencies, to act as the default mental health “treatment” facility in the county, a trend that has been seen nationally. I worked with Androscoggin County Jail (ACJ), in partnership with Tri County Mental Health Services, for my senior thesis, through which I became connected with the Harward Center’s Community-Engaged Research Fellows program. My research focused on quantifying the prevalence of mental illness among inmates at the jail and analyzing those prevalence rates within the context of recent changes in MaineCare and other public policies.

When I first heard about the Community-Engaged Research Fellows program, I thought it would be an exciting opportunity to bounce some research ideas off of other students. However, working with the Fellows gave me the opportunity not only to receive feedback and find support for my research, but also to connect with other seniors on their work. Over the course of the semester, I found that I loved hearing about the other Fellows’ research just as much as I enjoyed engaging in my own. As a self-designed major at Bates, I never participated in a Capstone or Senior Seminar class. Being a CER Fellow ended up providing me with a sense of academic community that I hadn’t realized I was missing until I became part of the program.

I initially chose to attend Bates because of the intentional relationships the college seemed to be building with its surrounding community. The Fellows program managed to combine academic passion that Bates is known for with an excitement for community connections within Bates and the greater Lewiston/Auburn area that had appealed to me from the start. As my senior year drew to a close, finishing my time at Bates as a Community-Engaged Research Fellow was the perfect concluding piece to my experience over the past four years.

Isobel Curtis

This past winter semester the Harward Center supported six Community-Engaged Research (CER) Fellows, varying widely in the topic and nature of their research. Our individual work was complimented by bi-weekly meetings where advice was exchanged over home-cooked meals. In this unconventional and intimate setting we discussed community research pedagogy as it applied to the challenging and rewarding aspects of our own work. What began as a collection of independent projects evolved into a support network– a collaborative initiative to strengthen the communities we were a part of. Each individual’s efforts were enhanced by the insight of their peers, who provided perspectives from fields of study completely different than their own.

My experience as a Harward Center CER Fellow helped me identify the underlying elements common to all work I have found most gratifying throughout my studies at Bates. I learned that personal connection to the people and places my efforts aim to benefit is fundamental to my definition of meaningful work. By forming these personal connections, I am able to realize the larger context of my work and frame the implications of my findings. For me this is the most motivating part of science and holds me accountable for the quality of work I produce. The act of forming connections becomes the foundation for the process of community building. Reflecting on my four years at Bates and our CER group in particular, it struck me that forming communities of individuals with similar goals allows for more dynamic problem solving and creative solutions. Though the scientific process is often seen as rigid and impersonal, in reality it is a very collaborative community that fosters connections among scholars. At the end of my junior year, I had become disheartened by the dry and formal research process and had trouble visualizing a future for myself in the field of research. I had not yet encountered the networks and communities that balance and give life to the scientific method.

In my final year at Bates I was fortunate enough to take part in many such communities, all different yet vibrant and resilient in their own right. I began working at Whiting Farm located in Auburn, ME my junior year through the Environmental Studies capstone in Community Engaged Research. Though I knew little about renewable energy prior to the project, I quickly became enthralled with geothermal energy and its potential to help farmers save money. As my time as a CER Fellow progressed, I found myself shifting from the familiar and expected role of researcher (i.e. operating behind a computer screen) to network builder. Progressive work was already happening on the renewable energy front, led both by farmers and renewable energy developers. Connecting Whiting Farm’s director, Kim Finnerty, to these human resources created a living network from which she could draw support after I graduated. At the end of the semester, Whiting had partnered with Shift Energy of Biddeford, ME to install Phase Change Material and temperature sensors in one of their many greenhouses. This technology works to lower heating and cooling costs by storing excess energy during the day and releasing it at night when the temperature drops. If quality data is collected, demonstrating the efficacy of this product, it can then be marketed to other farmers who struggle with the cost of greenhouse heating. Phase Change Material represents just one of many technologies being adapted from the residential market and tested in agricultural settings. By utilizing renewable energies to make year-round heated greenhouses a financially viable option, farmers in the northeast can provide their communities with a greater diversity of fresh food in the winter months.

In my final year at Bates I was fortunate enough to take part in many such communities, all different yet vibrant and resilient in their own right. I began working at Whiting Farm located in Auburn, ME my junior year through the Environmental Studies capstone in Community Engaged Research. Though I knew little about renewable energy prior to the project, I quickly became enthralled with geothermal energy and its potential to help farmers save money. As my time as a CER Fellow progressed, I found myself shifting from the familiar and expected role of researcher (i.e. operating behind a computer screen) to network builder. Progressive work was already happening on the renewable energy front, led both by farmers and renewable energy developers. Connecting Whiting Farm’s director, Kim Finnerty, to these human resources created a living network from which she could draw support after I graduated. At the end of the semester, Whiting had partnered with Shift Energy of Biddeford, ME to install Phase Change Material and temperature sensors in one of their many greenhouses. This technology works to lower heating and cooling costs by storing excess energy during the day and releasing it at night when the temperature drops. If quality data is collected, demonstrating the efficacy of this product, it can then be marketed to other farmers who struggle with the cost of greenhouse heating. Phase Change Material represents just one of many technologies being adapted from the residential market and tested in agricultural settings. By utilizing renewable energies to make year-round heated greenhouses a financially viable option, farmers in the northeast can provide their communities with a greater diversity of fresh food in the winter months.

Just as the Harward Center strives to root student research in the surrounding community, I believe fieldwork is necessary to ground students in the place or subject of their research. There is a depth of information that can only be obtained from an intimate understanding of the system you are attempting to study. Community-engaged research emphasizes working with community members for this same reason—because they have a far richer understanding of the problems at hand due to their lived experience. To draw a parallel to fieldwork, the researcher gains a better understanding of the system as a whole from direct observation, rather than simply analyzing select variables with little knowledge of the system they attempt to represent/reconstruct.

I argue that the process of data collection in the field is important because the researcher becomes familiar with the other variables present that may exert influence, thus creating capacity for intuitive insight. It is especially important for young researchers to engage in field work or analogous hands-on laboratory work. I view it as an exercise in active observation: What variables could I be missing? What alternative explanations could be explored? This past May I had the privilege of working with Laura Sewall, the director of the Bates-Morse Mountain Conservation Area (BMMCA), to plan and execute a habitat mapping initiative of the 600 acre property located in Phippsburg, ME. For those not familiar, Bates College manages BMMCA with the goal of furthering research and education efforts. Each year students take to the beaches and marshes to study topics ranging from dune migration to carbon sequestration. By providing a habitat map of the property, I hope to extend student research to the forested regions that cover roughly 70% of the property and create more opportunities for hands-on research.

While my work at BMMCA and Whiting Farm occupy different fields entirely, they are both deeply concerned with the concept of community resilience. In ecology, community resilience is defined as the ability to incur and recover from disturbance and is strengthened by community diversity and connectivity. Quite literally, BMMCA represents an ecologically resilient community composed of highly diverse habitat types. Yet, behind this pristine land is the network of passionate people responsible for its conservation. This group includes members of the St. John family, who originally owned the land and generously placed it under a conservation easement in 1976. At Whiting Farm, resilience grew from tapping into the burgeoning renewable energy network. By increasing connectivity between farmers and renewable energy companies, a lasting partnership was made that will ideally yield creative new solutions.

Faculty Spotlight: Professor Mara Tieken

Does education research matter for education practice? The ivory tower world of evidence and data can sometimes seem far removed from real classrooms and schools, and theory often has little relevance for actual practice. What would it mean to more tightly connect the two?

During Short Term 2017, fifteen students and I worked with the leadership of the Lewiston Public Schools to bridge that gap. Collaborating with Superintendent Bill Webster, Longley Principal Kristie Clark, and Martel Principal Steve Whitfield, we designed a research project focused on the upcoming merger of Martel and Longley Elementary Schools. In the process, we also developed our qualitative research skills.

Set to open in September 2019, the new elementary school will be one of the state’s largest. It will also consolidate two schools with very different cultures and student demographics, and district leaders recognize the need for a thoughtful plan to support their integration. In particular, the principals and superintendent wondered about their faculty and staff’s concerns about the merger, as well as their hopes for the new facility. And so, when I approached Superintendent Webster about the possibility of collaborating on a research project, he welcomed the opportunity and asked us to explore these issues.

Set to open in September 2019, the new elementary school will be one of the state’s largest. It will also consolidate two schools with very different cultures and student demographics, and district leaders recognize the need for a thoughtful plan to support their integration. In particular, the principals and superintendent wondered about their faculty and staff’s concerns about the merger, as well as their hopes for the new facility. And so, when I approached Superintendent Webster about the possibility of collaborating on a research project, he welcomed the opportunity and asked us to explore these issues.

We began the project by meeting with Superintendent Webster and Principals Clark and Whitfield to find out details about the merger and to better understand their perceptions of staff concerns and hopes. They were generous with their time and eagerly engaged our questions, and we developed a plan to first begin volunteering and observing in Martel and Longley classrooms to learn more about the schools and later conduct in-depth interviews with teachers and staff.

One of the challenges of community-engaged research is its unpredictability, and we confronted a surprise from the start. To get the best, most useful data possible, it quickly became clear that we would also need to survey the entire staffs of both schools—and we only had five weeks.

So we got to work, functioning more like a research team than a traditional class. We began volunteering in classrooms in both schools and talking over our informal observations. We wrote the survey, discussed it with the superintendent and principals, and administered it. By week three, we had started interviews. Our fourth week was devoted to data analysis—identifying themes, coding the interview data, cross-referencing with our survey results—and the final week concluded with a written memo for the staffs of both schools and a presentation to Superintendent Webster, Principal Clark, and Principal Whitfield.

At the project’s end, students reported they had learned a lot about designing a research study, writing surveys and conducting interviews, analyzing data, and reporting findings. They grew more comfortable with the responsibilities of conducting ethical research—like, for example, what it means to really hear someone’s story or how to think through the power dynamics of a research project. More than anything else, students said they valued the authentic collaboration—with teachers, with school leaders, and with each other. Yes, qualitative research can be messy and unpredictable and time-consuming, but it can also be useful. My students were excited to take part in a project that just might contribute to the successful start of a new school.

In The News

- $10,000 grant helps Gift Pola Kiti ’18 bring clinic to Kenyan village

- Student’s social enterprise pitch wins $9k Bobcat Ventures competition

- With Bates’ help, young leaders show true colors in a mural project

- There’s a big part of rural America that everyone’s ignoring

- In one town, how Mainers and new immigrants learned to coexist – until Trump

- Reason for recent French speaking resurgence in Lewiston: African immigrants

Want to know more about something in this newsletter, or have questions about the Harward Center or the civic mission of Bates College? Please contact Kristen Cloutier or visit us online.