Come together, right now

History professor John Cole strolled around the cramped Canham House seminar room, making quite excellent points about Voltaire. As Cole edged his way between the fireplace and the seminar table, where his students sat in various stages of alertness, he felt a sharp tug on his pants pocket and then heard a ripping sound. Looking down, the esteemed Thomas Hedley Reynolds Professor of History saw that his pants pocket had snagged on the fireplace damper handle, which jutted out from the wall.”I ruined a good pair of pants,” said Cole. “But I definitely got my students’ attention.”

Canham House, the home of the Bates history department, sits on a quiet section of Wood Street, which extends south from Campus Avenue toward downtown Lewiston. Like many of the spaces on campus occupied by the College’s social-science faculty, Canham House wasn’t designed as an academic building. It was a family home and served that purpose quite well until 1984, when Bates “recycled” the building for the history faculty. It was named for Erwin D. Canham ’25, former editor of the Christian Science Monitor and for forty-five years a Bates Trustee.

Like the other recycled academic spaces on campus, Canham House heaps petty and not-so-petty indignities upon its learned inhabitants and their students. Canham House, in fact, could be the poster child for one of the most ambitious construction projects in Bates history: a new academic building, a landmark structure to be built between Lane Hall and Smith Hall, overlooking Lake Andrews on the site of the present Maintenance Building, which will be torn down.

Groundbreaking is tentatively scheduled for 1997, with the College now reviewing architectural plans, and project bids scheduled for later in 1996. Bates is also discussing whether the $12.5-million project will be done in two phases (a five-year plan), or completed all at once (a two-year plan). Funding is one of the key issues: paying for a longer, two-phase approach is a less-daunting task.

Professor Cole’s torn pants, though an inflammatory incident, did not start the movement for a new academic building at Bates. The call first came in November 1989, when a campus group called the “Priorities Committee” identified Bates’s most pressing needs. Near the top of the wish list was a new building to house the social sciences (anthropology, economics, education, history, political science, psychology, and sociology) and four of the College’s interdisciplinary programs: African American studies, American cultural studies, classical and medieval studies, and women’s studies. In making the recommendation, the committee noted that available office and teaching spaces on campus were “exhausted.”

Professor Cole’s torn pants, though an inflammatory incident, did not start the movement for a new academic building at Bates. The call first came in November 1989, when a campus group called the “Priorities Committee” identified Bates’s most pressing needs. Near the top of the wish list was a new building to house the social sciences (anthropology, economics, education, history, political science, psychology, and sociology) and four of the College’s interdisciplinary programs: African American studies, American cultural studies, classical and medieval studies, and women’s studies. In making the recommendation, the committee noted that available office and teaching spaces on campus were “exhausted.”

If not for two other events, however, the academic building might still be on the wish list, not hurtling toward the schematic stage. The first was the completion of the Carnegie Science expansion and renovation in 1989. For the science faculty, the gleaming new space provided not only a great home for teaching and research, but it also attracted new science majors in droves.

The renovation of Carnegie created a glaring contrast between the haves (the science faculty) and the have-nots (the social-science faculty). Having toiled for years in a variety of renovated spaces on campus — from quirky Canham House to the labyrinthine basement of Libbey Forum — the social-science faculty began to grow increasingly aware of their hand-me-down status.

The other event that put the academic building on the front burner was the 1992 renovation of the Gray Cage into a multi-purpose space for large campus gatherings: parties, concerts, athletic events, and the like. While the project fell short of addressing another pressing Priorities Committee need — a new campus center — it solved a chronic space problem on campus. “We desperately needed a space for gatherings of more than 150 students, the limit of Chase Hall,” said Bernard R. Carpenter, treasurer and vice president for financial affairs. “The renovation of the Cage made it possible and pragmatic to address the needs of academic departments who are in much-less-than-desirable work environments, such as professors working in spaces where there’s no room for students to visit.”

The inconveniences endured by the social-science faculty seem like plot devices on a TV situation comedy.

An addition built at the back of Canham House a few years ago caused a special problem. When the downstairs seminar room (the former living room) is in use, anyone in the front part of the building — Michael Jones, for example, whose office is just inside the front door — must circumnavigate the seminar room if he wants to chat with, say, Avi Chomsky, the department’s Latin Americanist, whose office is at the back of the building. Jones, a medievalist, can either troop outside and use the side door, which bypasses the seminar room, or he can pretend he’s Hannibal and climb the stairs to the second floor, walk to the end of the hallway, and descend the stairs to the first floor.

On the second floor of Canham, Steve Hochstadt has a large office that he shares with colleague and wife, Liz Tobin. He has no complaints about the company, but says “it would be nice to be able to work with students without bothering her.”

And while Canham’s second-floor inhabitants, whose offices are former bedrooms along a narrow hallway, have a “shout-down-the-hall” repartee, the faculty on the first floor dare not raise their voices, lest they bother a class in the seminar room. “The building is oddly segregated both by floor and by the seminar room,” says Jim Leamon, the early-American historian. “We all get along very well, but the people on the first floor tend to be excluded from the easy camaraderie of the second floor.”

Libbey Forum, across College Street from Schaeffer Theatre, is another notorious academic building. Built in 1909 and resembling a train station, it was initially the happy home of the College’s literary societies (Polymnia, Eurosophia, Piaeria) and the Christian associations. These organizations nurtured the art of debate at Bates in the College’s early years, and their move into spacious Libbey Forum ensured that debate would become a hallmark of the College.

At its opening, Libbey was called “beautiful, substantial, and commodious.” Now, its reputation is odious. In the last thirty years Libbey has been recycled to meet pressing needs for additional teaching and faculty office space. The once dirt-floored basement, for example, is now faculty office space and a computer lab.

At its opening, Libbey was called “beautiful, substantial, and commodious.” Now, its reputation is odious. In the last thirty years Libbey has been recycled to meet pressing needs for additional teaching and faculty office space. The once dirt-floored basement, for example, is now faculty office space and a computer lab.

Sociology Professor Sawyer Sylvester has occupied one of Libbey’s basement offices since his arrival in 1969; in fact, the underground offices were created the year of his appointment to the Bates faculty. The possibility of moving above ground after twenty-six years intrigues Sylvester. “New offices might not provide the same protection against sunburn and high winds as the current basement offices do,” he admitted dryly. “But I would gladly exchange all this for a view.”

Like Sylvester, the other Bates social-science faculty have accepted quirky working spaces and isolation from colleagues outside their disciplines with good, if ironic, humor. In Canham, for example, there’s no room for mail slots in the tiny foyer, so the professors have taped their names to spindles on the bannister. When mail arrives, it’s tucked between the appropriate spindles on the appropriate stair.

These workplace shortcomings become less comedic and more tragic when one remembers that Bates doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The College must compete in the marketplace for students and faculty. A young and talented professor who yearns to teach and do research at a small liberal-arts college has dozens of potential employers besides Bates.

Following the 1993-94 academic year, a highly regarded, hard-working young economist with expertise in the post-communist economies of Eastern Europe left the Bates faculty for another small college. It wasn’t a surprise. Months earlier, a senior colleague had warned, in a memo to the administration, “We might lose [him]…. He has at least a couple of frustrations worth mentioning.” A basement office in Libbey headed the list. He felt isolated from students and colleagues in departments related to his cutting-edge work. If all the Bates social-science faculty were under one roof, said the memo, the young economist “could for the first time talk easily and often with the professors of Russian politics and Russian history. And there might even be public lounge areas [non-existent in Libbey or Canham] that would facilitate not only such professorial interaction but also spontaneous and casual meetings with students.”

Professor Cole, for example, teaches courses in Greek antiquity, yet he rarely sees the College’s classicist, Dolores O’Higgins, even though the two professors share students and similar professional interests. She’s in the Department of Classical and Romance Languages and Literatures, and her office is way across campus in Hathorn Hall. “A college like Bates ought to be very good at giving students access to faculty and providing opportunities for faculty interaction,” said Cole. “But with recycled frame houses on the outskirts of campus, that just doesn’t happen.”

The social sciences are, indeed, scattered throughout campus like tiny, gated communities: economics, sociology, and anthropology in Libbey Forum at the foot of Mount David; political science in the shadow of Carnegie Science on Campus Avenue; history in Canham House on the southwest fringes; psychology smack dab in the middle of campus in Coram Library; and women’s studies and education at 111 Bardwell Street, off Campus Avenue. The faculty who teach in interdisciplinary programs like American cultural studies, African American studies, and classical and medieval studies have no place to gather whatsoever; instead, they work in offices around campus and hope to see each other once in a while.

These departments sit in geographic isolation, yet everything in academe points to a coming together of various academic fields. As the Cole/O’Higgins example suggests, the boundaries between disciplines are dissolving as faculty in different fields find common threads running through their areas of expertise. Dean of the Faculty Martha Crunkleton puts it bluntly: “Today, hard-core academic specialization is incestuous.” Instead, she says, the division between disciplines should be like “a breathable membrane” with shared information and interaction between the porous division.

Teaching, too, has become less autocratic and more collaborative, another reason Bates suffers without new teaching spaces. The lecture is still a mainstay of the academic scene, but teachers are moving away from the “me talk, you listen” teaching style. Instead, they interact with smaller groups of students outside the lecture hall, often with a computer as a focus.

Current teaching and office spaces, however, discourage a collaborative teaching approach. In the dingy basement of Libbey Forum (which Crunkleton calls “Kafka-esque”), economist James Hughes struggles to fit students into his office space. “I’d like to structure my work space so I could work on the computer with small groups of students without constantly rearranging my furniture,” he said.

And if faculty can’t work with students in their offices, they spill out into classroom space. As a result, the demand for small seminar rooms has far outstripped the College supply. “Faculty want to break out into small groups, rather than use a traditional lecture mode of teaching all the time,” said Meredith Braz, the College registrar. “There is definitely a shortage of good seminar rooms on campus. So sometimes faculty meet in offices, lounges, or other space on campus, just to keep from being scheduled into a vast space.”

Sandy Howe, the Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott architect working on the proposed Bates building, acknowledges that he’s faced with a long list of expectations for this ambitious project. “We want this building to generate interaction among students and faculty that was never conceived of before,” he said. “The effort is to blur the line between master and pupil, to break down those traditional boundaries.”

Those boundaries were very much in evidence the last time Bates built an academic building. It was 1953, the Iron Curtain had fallen in Europe, and Pettigrew Hall was completed on the Bates campus. Pettigrew is the traditional, severe model of an academic building: a dreary entrance foyer, “double-loaded” corridors, and no lounge space for casual interaction. The hallways might be filled with people between classes, but once doors close and classes begin, a hallway visitor feels alone, abandoned, and very much out of place.

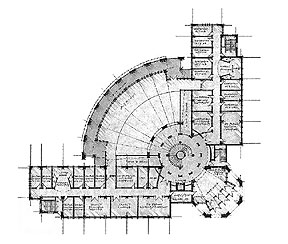

The design for Bates’s new academic building looks like a baseball park. Two wings (the left and right field stands, if you will) extend north toward Smith Hall and west toward Lane Hall. Their nexus — home plate — is the main entrance off Andrews Road. Filling the space between the two wings — the infield and outfield — is a large atrium with windows facing Lake Andrews.

The design for Bates’s new academic building looks like a baseball park. Two wings (the left and right field stands, if you will) extend north toward Smith Hall and west toward Lane Hall. Their nexus — home plate — is the main entrance off Andrews Road. Filling the space between the two wings — the infield and outfield — is a large atrium with windows facing Lake Andrews.

Entering this academic ballpark from behind home plate, a visitor will feel at once welcomed and drawn toward the teaching spaces and faculty offices within, said Howe. The first welcoming device is a generous vestibule, which leads to a grand staircase going all the way from the ground level of Lake Andrews to the upper floors of the three-story building.

Bates learned the importance of an attractively designed vestibule when the College modernized and added to Carnegie Science Hall. “The vestibule in Carnegie was a controversial space,” said Carpenter. “The science faculty, understandably, didn’t want to see good space wasted by not assigning it to some function. But the space has since become very popular. It’s where faculty can meet casually, to have a cup of coffee. When you walk in, you feel you’re in a meaningful space, as opposed to a space that’s just a way of getting from here to there.”

A major question was how best to orient all the classroom spaces, faculty offices, seminar rooms, laboratories, and department lounges in the new building. The answer came after extensive interviews with the faculty who will use the building. “The issue is accessibility,” said Howe. “You have to have a centering device within each academic department, from which the `reach’ to any faculty office door is not too distant.”

That “centering device” is the department lounge. Howe says to think of the entire academic department as a four-spoke wheel. The lounge is the hub — the resource center for the department, the place where a visitor senses the identity of the department and where, for example, color pictures of the department members might be displayed on a wall. The not-too-distant faculty offices are one spoke off this wheel, the twenty-five-person seminar rooms are another spoke, the larger classrooms in the building another, and the laboratories or other special features the fourth spoke.

The faculty offices themselves will be large enough to accommodate “as many different styles of living and being a faculty member as you could possibly think of,” said Howe. “Yes, there would be the occasional member for whom the space would be a private scholarly retreat, a room lined with books. But then there are faculty who want a small seminar space, a space that could be used by students even when the faculty member isn’t around.”

The building’s classroom spaces will welcome different teaching styles and feature new multi-media technology. “Faculty have legitimate pedagogical reasons for wanting a specific kind of teaching space,” said Meredith Braz. “It’s obvious that a chemistry course needs a laboratory, but now math and economics courses require computer capabilities. Language courses also require computer labs, as a place to practice pronunciation, and more courses require projection screens.”

Bates is keenly aware that a new building must also handle future, albeit unknown, needs. “Bates is engaged in some visionary thinking,” said Howe. “This is a building that isn’t just a classroom building and isn’t just a faculty office building. It potentially could have some completely other use.”

“Bates must build things in such a way that they can change their function,” said Carpenter. “It’s a lesson we learned with the Carnegie renovation. Space designed for storage has already been turned into active academic space.”

In the new building, says Howe, the configuration of space can change as academic needs change. “Everything must be planned so that two faculty offices, for example, could become a seminar room. Or a standard twenty-person classroom could be made into three faculty offices.”

The building’s signature space — one of the so-called “hard spaces” that defines the very essence of the building — is the 8,000-square-foot, three-story atrium that looks out over Lake Andrews. The space has been made possible by a $1-million gift from Ralph T. Perry ’51, made in memory of his late wife, Joan Holmes Perry ’51. At different times, the atrium will offer space for social events, space for academic gatherings, space for exhibitions, or space for quiet relaxation and reflection.

“It’s got to shine; it can’t be hidden,” said Howe, describing the challenge of designing the atrium. “Your normal atrium building would not do what we’ve done: A normal atrium would be buried in the middle of the building. This one is definitely intended to look out onto campus; in fact, it’s not really an atrium, but more of a crystal palace — that type of room. It’s got to have a vision on the world, as opposed to simply being inward looking.”

And that, perhaps, is as proper a theme for this ambitious project as any.