Popham Beach vs. the River

The meandering Morse River ends its assault on Popham Beach

By Kirsten Weir

The Bates Outing Club clambakes at Popham Beach State Park are one reason this sandy stretch of Maine coastline is a touchstone of the Bates experience.

Longtime BOC adviser Judy Marden ’66 recalls the clambake ritual from her Bates days: “The night before, we’d go out and gather driftwood, then camp overnight. Early the next morning we’d dig pits and start the fires. Then we cooked the lobsters in trash cans with clams and corn.”

But in spring 2010, the state asked the BOCers to relocate their clambake, which they did, to Reid State Park a few miles to the east. The reason: There’s not much public beach left at Popham.

Indeed, while an idealized and immutable Popham looms large in the alumni consciousness, the beach itself has rapidly eroded during the 2000s. These days, only a few feet remain at high tide.

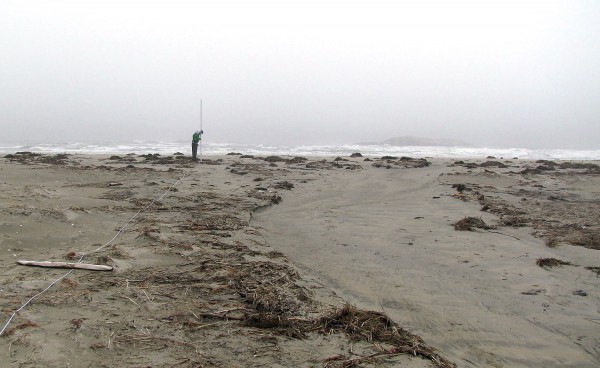

The roiling sea in December 2009 threatens the picnic area at Popham Beach. Photography by Stephen Dickson.

If Popham Beach is this story’s protagonist, then the antagonist is the Morse River, which exits the coast just west of Popham Beach. In recent years, the river has migrated eastward, cutting away at Popham’s beach, particularly the western part of the beach, though the center beach, which connects to Fox Island, has also been eroded significantly.

“We’ve been watching this river shift its course gradually for a long time,” says Bates geology professor Mike Retelle. By 2005, he says, “we started noticing massive changes” to the Morse River and Popham Beach.

Two factors pushed the river toward the beach. “A double whammy,” Retelle says.

One was the relentless growth of a sand spit just offshore from the Morse River outlet. The spit was created by a wave and sand mechanism called longshore sand transport, in which sand-carrying waves hit the shore at an angle and gradually deposit their sediments. Retelle and Dana Oster ’09 dubbed the Morse River spit “I-95” for its great length and width, and it became an “insurmountable barrier” that blocked the Morse from flowing directly into the ocean.

This aerial photograph of Popham Beach on March 10, 2010, shows key elements of erosion: (1) the new channel cut by the Morse River last winter, which should save the beach; (2) the old channel that for years had eroded the west side of Popham; (3) the tombolo that makes it possible to walk to rocky Fox Island at low tide. Photograph by John Picher.

The sand spit deflected the river toward the beach, and the erosion just got worse and worse. “It was like a firehose,” Retelle says. As kayakers and canoeists know, when a river curves, the fastest and most powerful flow is the outside of the curve. As the Morse curved into Popham Beach, the strongest part of the current was eating away at the beach.

“You want to see natural processes play out,” Retelle says.

River outlets are always “the most dynamic places” along the coast, says Retelle. Even so, the stunning changes at Popham had observers “in a panic” by this past winter, Retelle says. Erosion had carved deeply into the dunes and toppled hundreds of shoreline pine trees. The ocean was within feet of the parking lot, and it threatened the park’s new bathhouses. State geologists say it’s the beach’s greatest retreat in a century.

In its inexorable eastward march, the river had even cut through the sand bar, known as a tombolo, making it nearly impossible for visitors to walk from Popham to Fox Island.

This past February, some local residents urged that a channel be cut through the sand spit to allow the river to return to a north-south orientation. But others said that the river, and nature, should take its course.

This seaward-looking view of the beginning of the new channel across the sand spit was taken on April 7, 2009. Note how the seaweed, wood and other debris have been cleared from the area of fastest flow. Photograph by Mike Retelle.

“From an environmental perspective, you want to see natural processes play out,” Retelle says. “Otherwise you won’t know what would have happened.”

The Bates–Morse Mountain Conservation Area is just across the Morse River from Popham Beach, and director Laura Sewall also opposed taking action.

“The mission of the conservation area emphasizes protecting ecological integrity and educational opportunities. That’s primary,” says Sewall.

She subscribes to a philosophy promoted by naturalist Aldo Leopold, she explains: “If you want to understand a natural system, you can’t study one that has already been in any way altered.”

While public attention peaked over the winter, scientists like Retelle and state geologist Stephen Dickson had already seen evidence that the river was about to change course.

In April 2009, as Retelle and his students were doing measurements on that aforementioned I-95 sand spit, they saw a dry channel right across the spit, about 2 meters wide — evidence that the river had momentarily breached the spit during a recent storm and its associated high tide.

From left, thesis students Dana Oster ’09 and Emily Chandler ’09 walk with geologist Mike Retelle at Popham Beach and the adjacent shoreline near Bates-Morse Mountain Conservation Area. Together they monitored sand transport and erosion, using tools like automatic level, used to measure the elevation from the water’s edge to the higher ground of the beach, and a stadia rod. Photograph by Phylis Graber Jensen.

According to Dickson, the channel was the first sign of “a new, and more direct, course to the sea across the…spit.” In fact, winter storms had begun shaving the sand spit little by little over the last two years, Retelle says. He and Dickson agreed that a few more fierce winter storms would do the trick.

On Feb. 25 and 26, 2010, a major northeaster proved them right, as gale winds and high tides helped the Morse River barrel through the mound of sand to create a new north-south flow away from Popham Beach.

“I never know what I’m going to see when I go down to Popham.”

With summer’s arrival, calmer wave action should allow sand to be re-deposited along Popham, explains Retelle, so the beach should begin to grow again. In fact, Retelle and his geology thesis student, Molly Newton ’11 of Easthampton, Mass., are now working with the state to monitor the recovery of Popham Beach.

It’s an intriguing project, he says. “I never know what I’m going to see when I go down to Popham.”

Kirsten Weir is a science writer based in southern Maine.