John Kenney ’42

John Kenney ’42 Lives the Sacred Oath

More than three decades ago, John A. Kenney Jr. ’42 left a lucrative private practice in dermatology to begin an academic career at Howard University College of Medicine, dedicating himself to the advancement of black physicians in dermatology.

It was a move that his contemporaries continue to remark about with amazement.

“Dr. Kenney is an example of the Hippocratic Oath,” says his long-time friend Albert Kingman, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. “He embodies the highest standards associated with being a role model. He was born into a tradition of service, high ideals, and loyalty to his race.”

Born in 1914, “Jack” Kenney always planned to be a doctor. “I heard that when I was three or four years old, I was found ‘operating’ on my grandmother’s leg with a frying pan,” he says, smiling at the recollection.

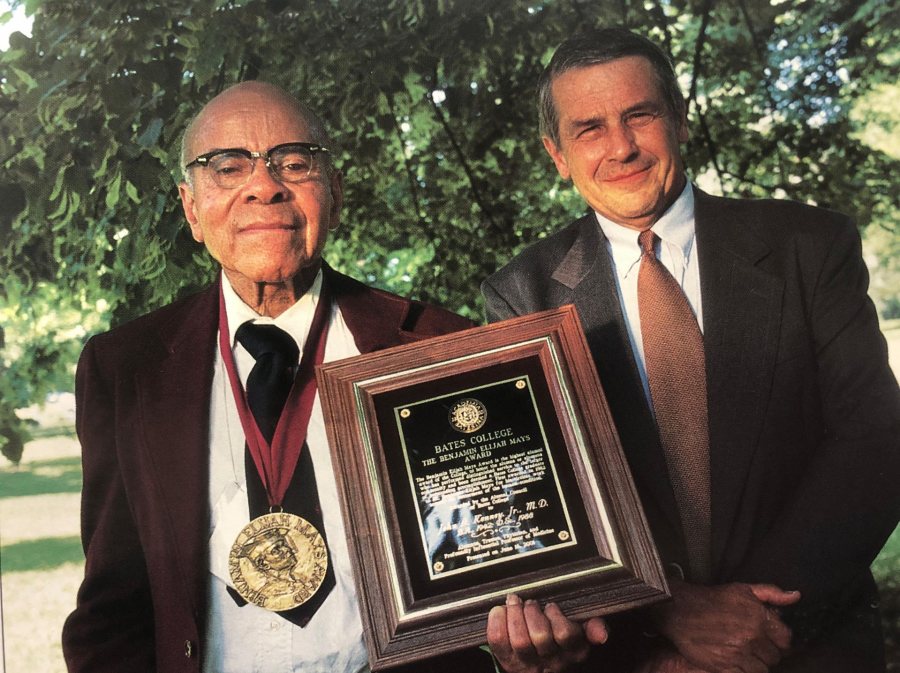

Dr. John Kenney ’42 (left) poses with Bates President Don Harward after Kenney received the Benjamin Elijah Mays Medal at Reunion on June 16, 2001. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

His father, John A. Kenney Sr., was medical director and chief surgeon at the Tuskegee Institute’s John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital. His mother, Frieda Armstrong Kenney, graduated from Sargent School of Physical Education (Boston University) and taught at Tuskegee.

His mother, he recalls, had a beautiful singing voice and kept their home well stocked with classical recordings to play on the family Victrola. Kenney came to love music and is a symphony patron and opera enthusiast today. His father maintained a wonderful garden, and on mornings when he wasn’t scheduled to perform surgery, he woke the children early to “come help Daddy in the garden.”

He grew up surrounded by many black academics and professionals at Tuskegee who were his parents’ friends. His father’s patients included such now-historic figures as Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver, who made a particular impression on the young Kenney. Every Sunday morning, Carver would take the three Kenney children on walks, stopping to identify plans by their botanical names and tell about them.

In 1922, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on the Kenneys’ front lawn. The white community was angry at his father because he insisted that the Veterans Administration Hospital being built in Tuskegee for black patients should be staffed by black physicians and nurses. Under a 24-hour guard provided by the Tuskegee Institute, Kenney’s father put his affairs in order and quietly moved his family north to New Jersey.

For his medical education, Kenney tried to stay in the North, applying to the University of Chicago and New York University, but during interviews there, admissions officers confided that the few spaces they had for blacks would be given to their own undergraduates.

He was accepted by the two black medical schools in the United States at that time, Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., and Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, and chose Howard because it was farther north. It was, however, still below the Mason-Dixon line, and as a student he was often “infuriated” by such restrictions as being unable to drink a milkshake in a drugstore or having to sit in the last row of a movie theater.

He graduated in 1945, and after completing his residency in dermatology at the University of Michigan, Kenney accepted an appointment at University Hospital in Cleveland. Kenney soon built a successful practice as Cleveland’s first black dermatologist.

In 1961, after eight years in Cleveland, Kenney was offered an assistant professorship at Howard. The salary was modest, and leaving his Cleveland practice would mean a financial sacrifice, but he felt strongly that his destiny was to advance black physicians in dermatology, and he accepted the offer.

Hearing about his decision, his friend John Haserick, then chief of dermatology at the Cleveland Clinic, reportedly said, “Jack Kenney has taken a vow of poverty.”

Kenney arrived to find Howard run-down and seriously underfunded. For example, it took a year to get his own phone line. The university would not allow him to accept a $5,000 Dermatology Foundation grant because “it was considered unfair to professors in non-medical departments who did not have similar grants available to them.”

During his many years as chairman of dermatology at Howard, Kenney achieved all of his major goals: establishment of a full dermatology department, a three-year residency program, and a dermatologic research laboratory.

“It took a real fight and some politics to get to be a department,” he recalls. The issue, as always, was money, but after laboring long and hard to make his case, the division became a department in 1970. “That was a big victory,” he says.

Despite the healthy growth of dermatology at Howard, Kenney believes the future of blacks in dermatology is currently in “jeopardy” because Howard has been targeted by the congressional budget cutters.

If funding at Howard is seriously curtailed, he forecasts that the effect on blacks in medicine will be profound, particularly in a specialty like dermatology with small numbers. “I would say Howard produced the majority of black dermatologists practicing today,” says Kenney.

Taking a new turn in his career, Kenney recently resumed private practice in dermatology, opening an office in Washington, D.C., in partnership with Roselyn Epps, who recently completed her dermatology training at the Mayo Clinic. Epps first met Kenney when he was her family’s dermatologist as she was growing up.

Like so many colleagues over the years, his new partner expresses great admiration for Kenney’s achievements, experience, and perspective, as well as his leadership in increasing the number of black dermatologists and fostering greater awareness of the unique dermatologic problems encountered by blacks. “He has the ability to always find the good in every situation and every person,” says Epps. “He is just a beautiful person. He’s a gentleman and he’s genuine.”

John Kenney, who received an honorary doctor of science degree from the College in 1988, is a Trustee emeritus. This article is excerpted from a “Master’s Bio” of John Kenney that appeared in Masters in Dermatology, Volume 12, Number 2. It is printed with permission of Cliggott Communications.