Unconditional, Genuine, Authentic

This story was published in Bates Magazine in 1997.

In the spring of 1949, Helen Papaioanou’s senior year, clothes started disappearing from the laundry room in Parker Hall.

“We finally realized it was a woman in our class,” Papaioanou remembers, still saddened by an event nearly a half-century ago. “One day, she had a suitcase and was on her way to the post office. The dean of women — Hazel Clark — sent me down to find her. `Have her come back with that suitcase,’ I was told.”

The student was caught with the missing clothes. And Papaioanou, as president of the Student Government, became involved in the disciplinary action.

Heading the faculty committee on discipline was Professor of Biology William H. Sawyer. “Dr. Sawyer was a strict disciplinarian, and we had some discussions,” Papaioanou said. “My plea was, `Look, this girl had been a model citizen. And as a campus community, we should support her and allow her to remain here.'”

But the College didn’t agree. Bates arranged for the student to go to another college and finish her last semester there. Although it was a better solution than expulsion, “it really hurt her family,” Papaioanou said. “She came from a very poor family and was about to be married. Students were upset. We tried to understand what happened.”

What still rankles Papaioanou today is that her College washed its hands of the problem, as opposed to dealing with the problem itself. “Until then, I thought of the College as always being right and always making the right decision,” she said. “I thought to expel her was inconsistent with what Bates was trying to be and to do. She was ours. This woman was not ‘bad.’ I thought we should deal with the situation ourselves and not send it away.”

“Helen Papaioanou does not take people lightly. She accepts you for all that you are.”

Jim Carignan ’62

She’s not cavalier, this Helen Papaioanou. Healing physician and tireless alumna, her outlook is characterized by devotion to the people and institutions around her. She insists on solving — not passing along — life’s problems.

“Helen Papaioanou does not take people lightly,” said longtime friend Jim Carignan ’62, associate professor of history and dean of the College. “She accepts you for all that you are.”

He should know. In 1988, Carignan began suffering severe heart problems that culminated in a 1993 heart transplant — that failed — and then another heart transplant, a week later, which worked. “Helen’s support was unconditional,” Carignan said. “Unconditional, genuine, and authentic. She would fly to Boston to see me. Call me. She would insist on helping financially, when Sally [Jim’s wife] needed to stay overnight. Always upbeat. Always positive. At the same time, she was making sure I was asking the doctors all the right questions and making sure I was getting all I was supposed to.”

The memory is emotional for Carignan. “I mean, you don’t play at being Helen’s friend. I mean, if she is going to be your friend, she is your friend. There is a completeness to that relationship.”

It is now April 3 on campus, the first of three days jam-packed with celebrations: the 142nd anniversary of the College’s 1855 founding, the successful conclusion of the Bates Campaign, Carl Straub’s inaugural lecture as the Clark A. Griffith ’53 Professor of Environmental Studies, and groundbreaking for the $17.5-million academic building.

“Helen just represents the best of Bates. There’s nothing phony about Helen: she loves Bates and she loves people.”

Jim Moody ’53

The kickoff event is Thursday’s Founders Day Convocation in Merrill Gymnasium. Papaioanou, who served as the national chair of the campaign, which raised $59.3 million against its $50-million goal, is to receive an honorary Doctor of Science degree.

![[Photo: Moody, Papaioanou, and Harward]](http://abacus.bates.edu/pubs/mag/97-Spring/helen.photo1.jpg)

It is now about an hour before that award. Upstairs in Merrill Gymnasium, in an alcove overlooking the lobby, Papaioanou and other Trustees are putting on robes and hoods. Spirits are high despite the last-minute news that the poet Maya Angelou, who is supposed to speak and receive an honorary degree at the Convocation, has postponed her visit.

Trustees and other VIPs are smiling and exchanging greetings. Helen is churning around the room, working off nervous energy. “Here we go,” she says. She’s all around the room: hugging Dick Coughlin ’53 over there, posing for a group picture over here with Trish Morse ’60.

Then, she’s over to the balcony, waving to her sister, nephews, and cousins down in the lobby. They all look up and smile. The Trustees, especially, are tickled that one of their own is receiving an honorary degree. “Helen just represents the best of Bates,” says a beaming Jim Moody ’53, Trustee chair. “There’s nothing phony about Helen: she loves Bates and she loves people.”

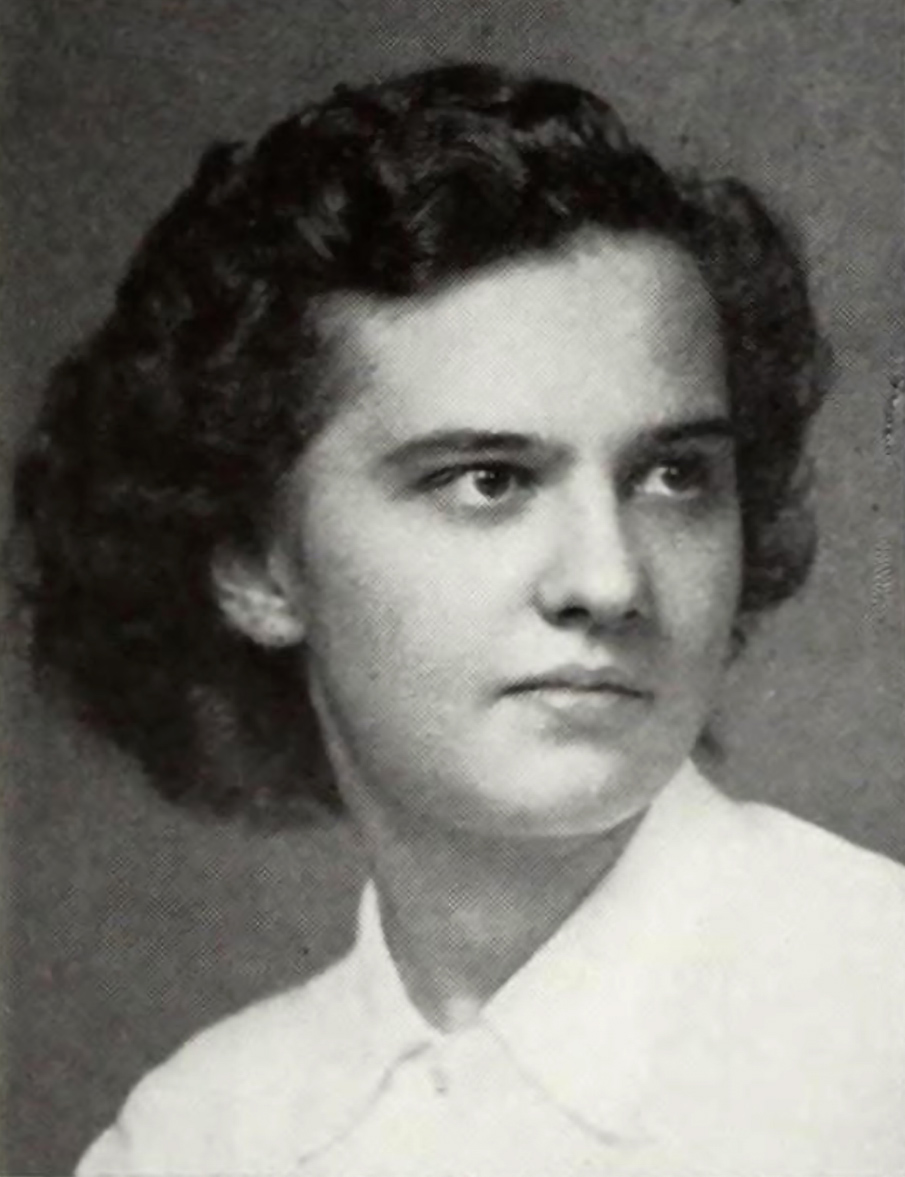

Helen Antonette Papaioanou (pronounced PUP-yoo-AH-noo) was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1928, on the eve of the Great Depression. Her mother was the daughter of an Italian immigrant. Her father was a Greek immigrant who left a tiny village in Greece when he was seventeen to come alone to the United States.

“He eventually settled in Springfield,” Papaioanou said. “He worked in a bakery before starting his own restaurant, the Welcome In Cafe. He spent the rest of his life in the restaurant business.”

His life was not what he wanted for his two daughters, Helen and Antoinette. He wanted them to go to college — an unusual wish in a first-generation Greek family. “Daughters were usually not educated. The expectation would be that a daughter would marry and have a family,” Papaioanou said.

While her father encouraged his daughters toward an educated, independent life, Helen saw the ache of regret in the eyes of her mother, who wished for — but did not achieve — independence in her own life.

Helen’s mother — Susie Raverta Papaioanou — was just a child when her own mother died of typhoid fever; Susie herself went to school only until the seventh grade. Then, like many other Greek and Italian immigrants who settled in river towns in Massachusetts, she went to work in the mills. She met John Papaioanou in Springfield, a city along the Connecticut River, where the Greek and Italian communities shared an affinity of geography and disposition.

“My mother worked very hard in the home,” Papaioanou said. “She probably wanted to work outside the home, to have had more independence, but the prospect of being out there alone — being different — frightened her. She was intimidated.” Papaioanou remembers, as a teen-ager, giving a brief speech at the end of a summer Bible school. Her mother was there. “When I came back, my mother said, ‘How did you know how to do that?’ She was just amazed.”

In other areas, however, Papaioanou’s mother proved to be an enlightened model. One day, she sat Helen down and told her young daughter about the difference between men and women. “When I remember how many of my friends’ parents never talked to them about sex, what my mother did was a very forward thing to do. I so respected my mother for that,” Papaioanou said.

“I probably just held my breath and said, ‘Here we come. We’ll take it as it comes.’ That’s the way I approach a lot of challenges.”

Helen Papaioanou ’49

Though her father was Greek Orthodox, Helen’s mother was Baptist. As Helen began looking at colleges, the minister of their Baptist church told Helen about a small college in Maine with Baptist ties — Bates College. “I knew I didn’t want to go to an all-women’s school,” Helen said. “I wanted to be a part of a more realistic community. I thought that one needed interaction with everyone.”

She arrived at Bates — sight unseen — in the fall of 1945. “Bates was the only college I applied to. Can you imagine?” she said, laughing. “We packed a trunk and shipped it ahead. I took the train from Springfield to South Station in Boston, then the taxi to North Station to catch the train — the Yankee Clipper — to Portland. I was terrified. I thought, I’m never getting to college.

“I remember arriving and hoping I was prepared to do the work,” she said. “I probably just held my breath and said, ‘Here we come. We’ll take it as it comes.’ That’s the way I approach a lot of challenges.”

A bit unsure of herself, yet hard working and determined, Papaioanou found Bates to be a “place of magic” where she gained confidence and encouragement to pursue her dream — to be a physician. “Bates gave me so many opportunities to develop skills I had never dreamed of,” she said. “It exposed me to academic material outside of the sciences, which was so important — like Cultural Heritage — or even subjects like speech.”

Papaioanou was a serious student. “My father worked very hard to pay for my college, my sister’s college, and my medical-school education,” she said. “It gave me a great sense of responsibility.”

At Bates, too, Papaioanou began to realize she was part of a larger community that extended beyond campus. She tells the story of meeting — just briefly — Euterpe Dukakis and her husband, Panos ’22, who was a physician. The Dukakises were also from Greek immigrant families that had settled in Massachusetts.

One day, Papaioanou was waiting for the bus on the corner of Campus and College streets, when the Dukakises pulled up in their car. “Somehow they recognized me, perhaps because I was involved in campus activities,” Papaioanou remembers. “Mrs. Dukakis leaned out the car window, called me by name, introduced herself and Dr. Dukakis, and just said, `We are proud of you!’ And off they went.”

The stunned Papaioanou just stared. Awareness dawned on her: when it comes to the Bates community, you’re never alone. “In that one greeting, there was acknowledgment of a shared heritage. There was energy, enthusiasm, and great encouragement.”

By senior year, Papaioanou was preparing medical-school applications. Her mentor, Professor Sawyer, had written positive recommendations for her, but had also offered this caution: “The only drawback in the process is that you’re a woman.”

Her admissions interview at Boston University backed up Sawyer’s observation. The dean challenged her: “You do expect to practice, don’t you? We and the community are making a great investment in you, and we do expect that you will practice.” The implication, of course, was that a woman would marry after medical school and not practice medicine.

“I remember men in my class telling me that men needed to become physicians more than women did,” Papaioanou said. “They told me that women in medical school were taking the places that men deserved and needed. “Overall, my experience in medical school was terrific,” Papaioanou said. “But there were some disagreeable things.”

“I always wanted to be part of solutions, not part of problems. I always wanted to be part of something far bigger than myself.”

Helen Papaioanou ’49

For example, in her rotations, the chief resident in obstetrics (later president of the Massachusetts Medical Society) told Papaioanou, “I can’t stand women in medicine. So stay out of my way.”

She forged ahead anyway. “I guess I developed coping mechanisms early,” she said. “I just didn’t dwell on it. I moved ahead to do the work I had to do.”

Taking her medical degree from Boston University, she began living a philosophy that she’d developed as a teen-ager. “I always wanted to be part of solutions, not part of problems,” she said. “I always wanted to be part of something far bigger than myself.”

Papaioanou served her internship and residency in pediatrics at Boston City Hospital and the University of Michigan, then returned to City Hospital for a fellowship in child psychiatry.

Her first practice was in the Appalachian “hollers” of McDowell, Kentucky, a poor mining town, where from 1957 until 1959 Papaioanou served as head of pediatrics at a small hospital.

“For a physician, it was a remarkable experience. We were able to concentrate on practicing medicine, without assuming many administrative duties.” It was a sobering experience for a pediatrician. “We went into the schools, conducting physicals and the like,” she said. “But we didn’t find severe illness, because it was survival of the fittest. By the time children reached school age, those who has severe problems just didn’t survive.”

![[Photo: Papaioanou and Pettengill]](http://abacus.bates.edu/pubs/mag/97-Spring/helen.photo2.jpg)

If you deal with Helen Papaioanou long enough, you come away with seemingly opposed impressions. She doesn’t suffer fools or mistakes, yet her humility never dims, either. “She combines a fierceness to implement her vision with a self-effacement you don’t normally see with that kind of person,” said Carignan.

Carignan remembers back two decades, when Papaioanou, in her capacity as chair of the Trustee Committee on Medical Services, helped turn the College’s infirmary into a more modern health center. The task, said Carignan, “was a conceptual and organizational nightmare” that went beyond just a name change.

“Students had no confidence in the place,” recalls Papaioanou.

Remembers Carignan, “I used to get calls from the nurses saying, `John Jones has a temperature and will not come into the infirmary, Dean Carignan. Will you do please make him come in here?’ In student culture, the place had all the negative connotations that one associates with an infirmary.”

Papaioanou and Carignan worked to change the infirmary “from a place where you went when you were sick, to a resource for staying healthy,” said Carignan. “It was a very exciting time. For me, Helen was a great model for how a Trustee ought to function: intelligent questions, supportive encouragement.”

From McDowell, Kentucky, Papaioanou returned to Massachusetts to establish a private practice in suburban Westfield, near her hometown of Springfield. The year was 1959, and for a woman doctor with a difficult-to-pronounce last name (“it’s interesting,” she says, “children never have trouble with the name”), it took time to settle in. There was the local bank, where Papaioanou went for a mortgage on her home and office. “They didn’t give me the time of day,” she said. The president of a second bank was more cordial, though he suggested Papaioanou would get a better interest rate in Springfield. “I told him I appreciated the advice,” said Papaioanou. “But I also told him, `I’m going to live and work here in Westfield. I want to support this community. I wanted my mortgage with your bank.'”

Then there was the old doctor who started saying derogatory things about Papaioanou behind her back, saying she was “stealing” patients. She had to threaten legal action.

This initial experience upset Papaioanou. Typically, it did not discourage her. “Helen dealt with it with grace and never became bitter,” said Catherine Aborjaily-van Dissell, whose friendship with Helen began in Westfield and continues strong today. “But she’s no shrinking violet. She said what needed to be said in those situations.”

“I came into my own, in every way, in Westfield,” Papaioanou said. She got involved in the Methodist Church, became president of the hospital medical staff, was the founding member and president of a children’s guidance association, and served on the board of directors of a camp for retarded children. She received the Woman of the Year Award from the Westfield Business and Professional Women’s Association in 1964. And in 1965, Papaioanou became a Bates Trustee. No woman has served longer on the Bates board.

“I left Westfield with this thought: If another good thing never happened to me for the rest of my life, I would not have had a complaint in the world — it was that fulfilling an experience,” she said.

Papaioanou left Westfield in 1966. “The work became all-consuming, all-encompassing,” she said.

“She gave all her time to her community,” said Aborjaily. “She never said no.”

Papaioanou also recognized she was at a career crossroads. “I realized I would have to either commit to a private practice in pediatrics for the rest of my days, or subspecialize, which would narrow the scope of my practice but maintain my link to pediatrics.”

In Westfield, Papaioanou had noticed the inadequate care received by asthma patients. Some had to wait two months just for a consultation, and in another city. “There were so few physicians specializing in the field, yet the disease was becoming more common,” Papaioanou said. “People also didn’t consider asthma a serious disease, because it was believed to be psychosomatic and stress-related. That’s because we just didn’t understand it.”

In 1968, Papaioanou completed a fellowship in allergy and immunology and earned a master’s of science degree. She set up a private practice in suburban Grosse Pointe, Michigan. The practice was successful — but unfulfilling. “I wanted to be working in a place where medical and social needs simply were not being met.”

That was the inner city of Detroit, where Papaioanou served as director of allergy at Children’s Hospital of Michigan from 1981 to 1991. She also taught (she had been named Instructor of the Year at St. John’s Hospital, Detroit, in 1978) at Wayne State University.

The next decade tested all Papaioanou’s abilities: she practiced, taught, lectured, researched, and administrated. “I enjoyed great successes, but also some great disappointments.”

There was the young boy with asthma, whose mother nevertheless smoked and had a menagerie of animals. “We spent hours trying to educate her,” said Papaioanou, but the boy was in and out of the hospital with asthma. “With asthma, you see the children frequently and you become personally attached,” she said.

“I can’t tell you how many nights I spent up with him in the emergency room, the office, the hospital. He would be crying, and I’d say, ‘Damon, would a hug help?’ And he’d leap out of the bed into my arms.” One day, the boy suffered a severe attack that left him permanently handicapped.

Papaioanou retired from the hospital in 1991 — receiving the Distinguished Service Award from Bates — and reentered private practice. In 1993, Detroit Monthly named her one of the area’s best doctors, in a survey of health-care professionals. Papaioanou retired fully in 1994, and now lives in Grosse Pointe City.

Helen Papaioanou never had children of her own. “It is so impressive the way women can combine family and professional life today,” she said. “Unfortunately, many women of my generation didn’t believe we had that choice. It was family or a career — we didn’t think we could have both.”

“Helen never resented the fact that she never had children of her own, and she always reveled in the accomplishments of the children around her,” said Aborjaily.

![[Photo: Papaioanou and Giuffrida]](http://abacus.bates.edu/pubs/mag/97-Spring/helen.photo3.jpg)

It is now a little before noon on April 3, and Dean of the Faculty Martha Crunkleton is concluding her honorary-degree citation for Helen Papaioanou.

Crunkleton reads: “For her life-long witness to the power of love and science in service to others, for her integrity and relentless optimism, for the model she has been for other women to pursue science at Bates, and for her ability to draw the friends and graduates of this College together to serve present and future students, I present Dr. Helen A. Papaioanou ’49, for the degree Doctor of Science.”

The applause begins and sustains, rolling through Merrill Gymnasium. A Trustee rises, followed by members of Papaioanou’s family and classmates, who are wearing pins with Helen’s picture. Then everyone — her Bates community: faculty, staff, students, alumni, and friends — stands for Helen.