A Stroll with Gomes

Gomes has arrived at Reunion ’98 with a flourish. He’s on the program to receive the College’s highest alumni honor, the Benjamin Elijah Mays Award (at which time he will label Bates’ founders “Baptist apple-pickers” — but you have to know the context). Indeed, in his brief visit, he’s creating some memorable moments. One moment comes early, this struggle with the arborvitae, viewed by a handful of quizzical alumni strolling by. The battle is actually a search for his class’s ivy stone. He finally finds the 1965 stone behind the bush, obscured by ivy. Affronted by the growth of ivy around several other stones, he rips away the tenacious tendrils. God’s work, indeed.Before his adventure in the bush, Gomes had visited the Alumni House for quick greetings. Then he made tracks for the College Store, where two popular items on this chilly morning were Gomes’ recent books — 1996’s best-selling The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart, and his just-published Biblical Wisdom For Daily Living.

Gomes has arrived at Reunion ’98 with a flourish. He’s on the program to receive the College’s highest alumni honor, the Benjamin Elijah Mays Award (at which time he will label Bates’ founders “Baptist apple-pickers” — but you have to know the context). Indeed, in his brief visit, he’s creating some memorable moments. One moment comes early, this struggle with the arborvitae, viewed by a handful of quizzical alumni strolling by. The battle is actually a search for his class’s ivy stone. He finally finds the 1965 stone behind the bush, obscured by ivy. Affronted by the growth of ivy around several other stones, he rips away the tenacious tendrils. God’s work, indeed.Before his adventure in the bush, Gomes had visited the Alumni House for quick greetings. Then he made tracks for the College Store, where two popular items on this chilly morning were Gomes’ recent books — 1996’s best-selling The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart, and his just-published Biblical Wisdom For Daily Living.

An alumna with Gomes’ new book in hand does a double-take, seeing the preacher both in the flesh and on the book’s cover. Noticing her surprise, and pleased to observe the crowd taking note of the author in its midst, the preacher adds some choice words to the moment: “And yes, I shall sign that for you, too!” Everyone laughs.

Quoted in a 1996 New Yorker profile of Gomes, Seamus Heaney, the Irish poet and Nobel Laureate, calls Gomes’ preaching style “grandiloquent…in a manner that is always on the edge of carnival.” On this Saturday afternoon in June, Gomes has come to the microphone at Merrill Gymnasium, the site of the Alumni Awards Ceremony, to say a “few words” in accepting the Mays award. The crowd is restless, having heard many citations, announcements, and pronoucements already. It is now just after noon, and Gomes is the only thing standing in the way of a stampede to lunch.

He captures the crowd early with earnest statements about the College’s role in his life, balanced by touches of what Heaney has described as “cadence, roguery, and scampishness, which is itself redemptive.” Gomes announces: “Except for my parents, I owe everything valuable, precious, and honorable to Bates…. My ultimate epitaph should be, ‘I went to Bates.'”

Pulling the crowd with him, he acknowledged the shadow cast by Benjamin Mays ’20 over his post-Bates years. “I was resentful of Benjamin Mays, because for years everyone I saw said, ‘You went to Bates?’ and then asked me, ‘Did you know Benjamin Mays?’ Of course, it was always my hope that maybe someone would say to me, did I know me?” The crowd tittering, Gomes delivers the scampish punch line: “Today, I do still get asked, ‘Oh, you went to Bates?’ But now the question is, ‘Do you know Bryant Gumbel?'”

Pulling the crowd with him, he acknowledged the shadow cast by Benjamin Mays ’20 over his post-Bates years. “I was resentful of Benjamin Mays, because for years everyone I saw said, ‘You went to Bates?’ and then asked me, ‘Did you know Benjamin Mays?’ Of course, it was always my hope that maybe someone would say to me, did I know me?” The crowd tittering, Gomes delivers the scampish punch line: “Today, I do still get asked, ‘Oh, you went to Bates?’ But now the question is, ‘Do you know Bryant Gumbel?'”

After the laughter passed, Gomes followed with a kicker to the heart: “Benjamin Mays said about Bates, ‘It was cold, but the people were warm.’ I completely agree.”

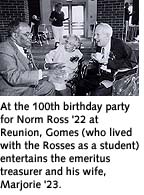

As this rhetorical rollercoaster continued — giddy moments of humor, passionate moments of appreciation — Gomes acknowledged that afternoon’s 100th birthday celebration for Norm Ross ’22 with anecdotes about the longtime bursar and treasurer. He quoted Aristotle’s definition of happiness — the “exercise of vital powers along lines of excellence” — and noted that excellence is at the heart of a Bates education.

Heaney says that “with Gomes, there is always an element of masquerade as he tempts the audience into complicity.” By the end of his talk, the Reunion crowd was rapt, ignoring the growing mounds of lobster rolls being unveiled by Dining Services. So Gomes was able to deliver a final rhetorical flourish, calling the Bates founders “strange, parochial people; tightfisted Yankees; Baptist apple-pickers,” whose practical, hard-headed intentions in the face of adversity (and opposition from neighbors north and south) gave birth to a great college.

He chose those colorful epithets for careful effect, Gomes said later. “One of the things I worry about, though it doesn’t keep me up at night, is that in our rush to become the best tiny, most selective college in the world, we will lose sight of our sturdy origins,” he said. “Whenever I get the chance, I want to remind Bates of that, because it is very easy and tempting to smooth over those origins.”

The “strange people” he’s talking about are the Freewill Baptists: “very ordinary people — unlike the snobs at [another college], people who were sensible, sound, solid, with unromantic, but very heroic lines. These were rural farming people” in tiny Maine towns like Hollis, Gorham, Durham, Gray, Parsonsfield, and Paris.

“For Bates people of my generation, that connection resonates with us because it was pounded into us,” said Gomes. “As long as we’re alive, we will have that connection to the College’s past.”