Lawyers, Guns, No Money

Tom Connolly ’79, struck down by a midwinter bout with influenza, sat huddled in front of his television. Semi-delirious, he watched Maine Governor Angus King wax poetic about Mainers’ heroic response to the historic ice storm a few weeks earlier. Charming the Augusta crowd as well as the television cameras, the Independent governor boasted that Maine was primed and ready for even more challenges: “Bring ’em on!” Back home in Scarborough, stripped to his underwear, Connolly began a slow burn, thinking of the suffering he’d witnessed in the previous weeks. A friend’s propane burns. A neighbor’s broken hip. A heart attack suffered by the husband of his children’s babysitter. “Bring ’em on?” he cried out to no one in particular. “I’ll bring on another one,” he thundered, terrifying his wife, “and when I do, it will be a firestorm!” The very next morning, Connolly, a Democrat, picked up gubernatorial nomination petitions at the secretary of state’s office in Augusta. A few days later, he formally announced his candidacy. But by primary day in June, he had attracted only obligatory media and voter attention. He had raised just $21,477 to support his bid, a sum that prompted The New York Times to note, “The biggest spender in the [Maine] governor’s race, Mr. Connolly raised about enough to cover a California campaign’s dry-cleaning bills.” Yet Connolly won big in the primary. He was now the Democratic nominee for governor.

The very next morning, Connolly, a Democrat, picked up gubernatorial nomination petitions at the secretary of state’s office in Augusta. A few days later, he formally announced his candidacy. But by primary day in June, he had attracted only obligatory media and voter attention. He had raised just $21,477 to support his bid, a sum that prompted The New York Times to note, “The biggest spender in the [Maine] governor’s race, Mr. Connolly raised about enough to cover a California campaign’s dry-cleaning bills.” Yet Connolly won big in the primary. He was now the Democratic nominee for governor.

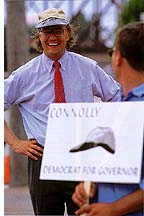

This was Tom Connolly, the Portland criminal defense attorney who started wearing a long-billed fisherman’s cap at Bates and forgot to take it off after Commencement. A respected, solo-practice lawyer with a lineup of controversial clients — cop-killers among them — Connolly now stood poised to run against Governor King, whose 70-percent approval rating, media charisma, and consensus-building management style prompt observers to call him “Clinton without the intern.”

That huge sucking sound on the Maine political landscape is the political vacuum created by the enormously popular King. “Connolly’s ability to win the primary in June was a function of King’s being able to win the election in November,” said Professor of Political Science Douglas Hodgkin, who taught Connolly as a first-year student in his American Political Parties course. With none of the Democratic Party regulars willing to make the sacrifice, Connolly’s chief competition in the primary was Joseph Ricci, a volatile racetrack owner whose distinguishing primary moment consisted of calling King “a pimp” at the state convention in May. (On the Republican side, the candidate is James B. Longley Jr., a conservative Republican and son of the late governor.)

Even in Maine, statewide campaigns typically cost in excess of $1 million, and “it’s very unusual to run a campaign for so little money,” Hodgkin said. Nor does the absence of funds bode well for Connolly’s success. “Without it, no one pays attention.” In fact, only 14 percent of Mainers voted in the primary.

Connolly’s platform is a classic liberal Democrat facade cracked with libertarian leanings. His economic “Marshall Plan” for Maine includes building an east-west highway, developing the U.S. Route 1 corridor, and creating economic development incentives. He would raise the minimum wage and pay for the first year of Maine college tuition for the children of Maine residents. A big part of his platform is combatting alcohol abuse through prevention and treatment programs and the restriction and taxation of liquor sales. Personal-privacy rights are also on his platform, an umbrella for several issues including gun-ownership rights — and he blasts the war on drugs in Maine, where the feds buzz rural areas each summer in helicopters, searching for marijuana plants. Ask Tom Connolly what tune he might sing to himself, and he answers “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” by Bruce Cockburn.

Connolly’s platform is a classic liberal Democrat facade cracked with libertarian leanings. His economic “Marshall Plan” for Maine includes building an east-west highway, developing the U.S. Route 1 corridor, and creating economic development incentives. He would raise the minimum wage and pay for the first year of Maine college tuition for the children of Maine residents. A big part of his platform is combatting alcohol abuse through prevention and treatment programs and the restriction and taxation of liquor sales. Personal-privacy rights are also on his platform, an umbrella for several issues including gun-ownership rights — and he blasts the war on drugs in Maine, where the feds buzz rural areas each summer in helicopters, searching for marijuana plants. Ask Tom Connolly what tune he might sing to himself, and he answers “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” by Bruce Cockburn.

“He has a lot of positions,” said Christian Potholm, the author of An Insider’s Guide to Maine Politics and a Bowdoin College government and legal studies professor. “But he’s not tailoring any of them to this election.”

“Connolly’s running a campaign similar to third-party candidates: not expecting to win but to educate the public on the issues,” Hodgkin said, adding that rarely does a major-party candidate today raise so many issues.

Potholm (a pollster for King) predicts that Connolly will snag second place in the November election with about 22 percent of the vote, trailed by Longley with around 17 percent, and the Green Party, unable to win the 5 percent necessary to be registered as a Maine political party.

As unknown to voters as a new line of yogurt without an advertising budget, Connolly is eager and willing to spin tales about who he is and what he can do. His campaign war stories paint a picture of overwhelming voter enthusiasm; they’re attracted to him like flies to honey. Does he really think he can win the race? Yes, but realism prevails. “I’m not foolish in saying it’s easy, but I’m optimistic because I feel I’m right, and I see that the future of the state can be very different by hard deterministic work,” he said.

As unknown to voters as a new line of yogurt without an advertising budget, Connolly is eager and willing to spin tales about who he is and what he can do. His campaign war stories paint a picture of overwhelming voter enthusiasm; they’re attracted to him like flies to honey. Does he really think he can win the race? Yes, but realism prevails. “I’m not foolish in saying it’s easy, but I’m optimistic because I feel I’m right, and I see that the future of the state can be very different by hard deterministic work,” he said.

He says he’s wooing the Democrats and converting the Republicans in droves, though his fund raising had netted only about $40,000 by September, a tenth of King’s total. During a visit to an Oxford Hills Kiwanis pancake breakfast, Connolly told how he transformed a 96-year-old lifelong Republican who had voted for Wendel Wilkie in 1936. A foe of the New Deal and New Frontier, she’d opposed every Democratic initiative to come down the pike in the last 60 years — until she met Tom Connolly. Two seconds of person-to-person with Connolly, the candidate claimed, and she was begging for bumper stickers. Connolly will tell you that a cop he sued for civil-rights violations gathered signatures to put his name on the ballot. A cabby struck in the head by one of Connolly’s illustrious clients contributed $25 to Connolly’s campaign — and plans to give more.

Swallow what you will, but why not, because a rhetorical ride with Connolly is unabashed fun. Who else would admit writing a candid poem to a federal judge accusing a big multinational corporation of killing his client for money? What other lawyer running for public office would demonstrate, holding a toy handgun and skull in his office, how his client shot someone? One minute Connolly is talking about labor issues. Next it’s Diogenes. As offbeat as Connolly is, he does have the gift. Truth be told, he loves people as much as he loves the catharsis of talking.

This middle-class, Irish Catholic baby boomer answers “two words” when asked what forged his liberal bent: “Dorothy Day. The Catholic Workers Movement.” That’s six if you’re counting, but if you’re willing to listen, he’ll unleash a heartfelt rainstorm of hundreds more. The Canton, Mass., native talks about the education he received from Xaverian Brothers High School in Westwood, Mass., where the liberal brothers — some of whom entered the priesthood to avoid the Vietnam draft, according to Connolly — helped shape his political outlook.

He’s quick to credit his grandmothers as well. One, an Irish Catholic immigrant with a strong democratic sensibility, was handed a pail and scrubbed floors for her keep. The other, Gam — an old Maine Yankee who wrote letters and signed petitions for her causes — fired his political ambition. “I sat in Gam’s lap watching Perry Mason. That’s why I became a lawyer.”

Like many Maine politicians, Connolly has identified the two Maines populated by the haves and the have-nots. As a defense lawyer, he just happens to know the “nots” a lot more intimately; as a liberal politician, he believes the state can — and should — ease their suffering. He fairly bleeds with anguish in talking about the plight of the poor, whether they’re single head-of-household females who earn $.69 to every dollar earned by men or the 70 percent of Aroostook County kids with untreated dental problems.

Connolly sees King, a former liberal Democrat himself, as a traitor to the party. He practically foams at the mouth when he hears his nemesis quote from Connolly’s patron saint, Bobby Kennedy. “King has abandoned the Democratic Party. He quotes Winston Churchill: ‘If you’re not a liberal when you’re 20, you have no heart; if you’re not a conservative when you’re 40, you have no brain.’ Bobby Kennedy was over 40 when a bullet entered his brain. A lot of us are more than 40 and believe in those things.”

He calls himself a poverty lawyer, and many of his clients are court-appointed. Professor of Rhetoric Robert Branham, Connolly’s debate mentor at Bates, thinks the lawyer created a niche for himself early in his career. Judges pegged the fledgling, workaholic attorney, fresh from the University of Maine Law School, as someone who would take court-appointed cases with supreme zeal. With more than 200 criminal trials now under his belt, he has treated each and every client — the wifebeaters, the drunken drivers — with the identical sense of what he calls “duty and obligation.”

While the candidate comes across a bit wired on television, his high-energy approach creates chemistry with voters and reporters in person. “He’s a charming guy,” said Branham, who watched as a witty Connolly disarmed journalists with his primary-night candor. “Eventually people become impressed with his sincerity even if they don’t agree with him on issues.”

At a Fourth of July celebration in Lewiston, the candidate worked the crowd filled with memés and parents pushing children in strollers. As a Christian rock band warmed up the exuberant crowd, Connolly was warming up a group of leatherclad Saracens on Harley-Davidsons (one was a former Connolly client). High-fives all around, he sent them packing with stickers for their bikes.

On a steamy summer afternoon in Portland, as hundreds of daycampers streamed into a Sea Dogs minor league baseball game, Connolly worked the entrance to Hadlock Field, gamely handing out handshakes and introductions. One tiny old woman, upon having her hand grasped, suddenly started pumping his appendage wildly. Turns out, Connolly said, she was none other than a juror from the notorious Nicolo Leone murder trial, in which Connolly defended a man accused of killing a Lewiston police officer. Amidst threats on his life, Connolly argued self-defense and got a manslaughter conviction instead of murder. Stooping from his lofty perch as she beamed at him, they exchanged a few enthusiastic words. “She loved me!” he crowed.

But the hat, always the hat. Discussing Tom Connolly without mentioning the hat is like talking about Bates while avoiding the word “egalitarian.” “I don’t have to tell you he has made himself distinct with his bill visor lobster hat. It certainly has set him apart,” said Vincent McKusick ’44, the retired Maine Supreme Court justice who is now a senior counsel for the Portland law firm Pierce Atwood.

But the hat, always the hat. Discussing Tom Connolly without mentioning the hat is like talking about Bates while avoiding the word “egalitarian.” “I don’t have to tell you he has made himself distinct with his bill visor lobster hat. It certainly has set him apart,” said Vincent McKusick ’44, the retired Maine Supreme Court justice who is now a senior counsel for the Portland law firm Pierce Atwood.

“He’s no kook. Tom is bright and articulate and has established himself as a very successful trial lawyer. He’s entirely respected within the profession,” said McKusick, who sat as presiding officer when Connolly argued several cases before the Maine Supreme Court.

Although the legal community has enjoyed a few laughs at Connolly’s expense over the hat, McKusick suggests the young lawyer has leveraged a victory by wearing it. “He has elected to set himself apart professionally with the hat, but lawyers have to stand out from the crowd. It’s a competitive field.”

Connolly’s doing the same thing in politics: crafting an image. With no money, what else does he have to work with? “The hat is his first entrée,” Hodgkin said. “Without the hat, who is he?” Potholm looks at the hat and concludes that Connolly is as interested in winning as he is in pursuing the issues. “Why else would he put a hat on all his campaign materials?”

Connolly (whose brother William is a member of the Bates Class of ’73) said he started wearing the hat at Bates when he couldn’t grow a beard. But since then, he’s used his hat to define himself. Carl Straub, professor of religion and dean of the faculty at the time, remembers that Connolly’s hat seemed important to its wearer but not to anybody else, although “the constancy of the hat raised a point of concern around manners.” Connolly explained the philosophy behind the symbol in his famous address, “On Wearing a Hat,” at the 1979 Senior-Faculty Dinner. He delivered the treatise wearing the fisherman’s hat, adorned by a tassel. “There are certain symbols of a person’s life,” he remembers telling his audience. “This hat has become my badge of education.” He admonished the guests not to judge others by “worldly aspects” (or hats) “but by being able to look beyond them, and look beyond yourself.”

Appointed as an assistant debate coach at Bates in 1979, Connolly said he quit the job even before he started because then-President Hedley Reynolds told him he’d have to remove his hat in the classroom.

Now he’s stuck with the hat, he says. If he removed it, everyone would be disappointed. His campaign visibility might disappear as well: besides sitting on his head, the hat appears prominently on his campaign literature. It disappears for court appearances, and lately, he’s removed it at various times during the race. “I’ve tried to de-fang it to calm people down.” His biggest fear is caving in to demands. “If you listen to it all, you’ll find you are bleached out white.”

Connolly must quickly craft a distinct public image because he can’t depend on the party for much support — financial or otherwise. “The party used to do it all for you,” Hodgkin said. “Today you can’t rely on your party organization.” In general, Connolly’s candidacy has tended to frighten the centrist elements of the state Democratic Party. “Party regulars treat me like Sidney Poitier in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” he said.

Yet Potholm said that Connolly’s candidacy just might unite the party’s traditional factions. “Connolly won’t win but he’ll strengthen the party’s hand in the future,” returning to the fold traditional Democratic constituents — unions, the Irish- and Franco-American ethnic vote, and leftist liberals who transferred allegiance to the environmental Green Party.

An outsider to traditional party politics (his only other political experience is serving as a Maine delegate to the 1996 Democratic National Convention), “my learning curve is still kind of blunt,” Connolly said. On Maine’s top-rated morning radio show just after the primary, when asked if he would stop his law practice to campaign, Connolly joked, “No way. Got to pay the bills. So, folks, by all means, go out and drink and drive so I can defend you.” He took a lot of heat for the comment, but good attorney that he is,argues a defense: “My chance of making large errors, faux pas, or political misstatements is much higher than a conservative, traditionalist, structuralist candidate.”

The juxtaposition of Connolly and King is striking. One day shortly after the June primary, Connolly was in court snaring three counts of “not guilty” for his client charged with burglary (the jury was out for 12 minutes), while King was at a blueberry festival. “In the whole history of Maine, I can’t find another gubernatorial candidate doing a jury trial,” Connolly said.

A day in the life of Tom Connolly can seem overwhelming. He and his wife, Elaine, a registered nurse, have three young children, Clancy Anne, Katherine Grace, and Thomas. Juggling schedules is a challenge familiar to any young family, particularly when dad is running for governor. With Elaine out of town for a week, it was left to the candidate to prepare a jury trial, drop the children at daycare, and march in a series of weekend parades with little Connollys in tow: one in a stroller, another ambulatory, and a third melting down in his arms. When talking about his kids, Connolly can get downright sentimental: “The one thing I’ve changed my mind about is not being able to love more after the birth of my first child. I have three, and the love expands, not diminishes.”

Located in his crammed, brick-walled law office in the Old Port, Connolly for Governor headquarters is a minimalist operation on two floors. He used to live here, too, working without a secretary for the first four years. With phone and fax lines constantly jammed, the candidate’s legal secretary, Ida Bilodeau, perseveres on all fronts. Assisted by one staffer, campaign manager Jim Betts — a veteran of Joe Brennan’s unsuccessful 1996 Senate campaign — operates out of his own home and Connolly’s law library.

This is it, says Connolly, likening himself to the man behind the screen in The Wizard of Oz. The lanky, six-foot-three Connolly seems almost lost behind the desk in his second-floor study, covered from top to bottom with legal documents, dust balls, and courtroom souvenirs. There’s a toy gun, a Dan Wesson 357, and an 1862 Civil War musket presented to him as partial payment for a divorce case. A bust of Abraham Lincoln perches in one corner, while Mr. Bones, the model of a human skeleton, stands at attention just behind the desk chair.

Most of the campaign is run out of his Toyota wagon, filled with bumper stickers, little orange antenna balls, cards, and buttons. “I get most things done by driving one place, jumping out, giving a speech, shaking hands, jumping back in the car, and driving somewhere else,” he says.

Connolly ends many campaign addresses by adapting a speech made by Caesar Chavez in 1968. In the speech, Chavez spoke of the motivation for his life’s work, and concluded by asking God to make him a good man. Connolly tailors his kicker for a 1998 crowd: “God help us to be good Democrats.”