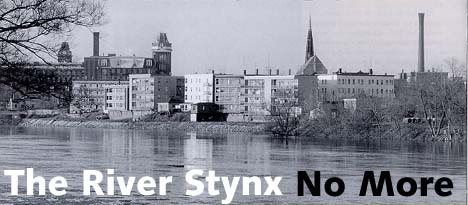

The River Stynx No More

Once grotesquely polluted, the Androscoggin River has rebounded in styleBy Michael GordonReprinted in edited form from theLewiston Sun Journal

It was a sad river that Ernest Additon toiled beside. “Floaters” — cakes of waste from paper mills and town sewers — choked the water that crept past his Leeds farm. Noisome gases bubbled to the surface, whipping up a meringue-like foam. It was a sight to turn the strongest stomach. But it paled in comparison to the smell. Pungent as rotten eggs, the stench assaulted the senses and, rumor had it, even peeled the paint off houses. As he tilled the land in the ’50s and ’60s, the fourth generation of his family to do so, Additon would reflect on the Androscoggin, on the sorry and awkward state it was in. “He used to say the river was too thick to paddle, too thin to plow,” his grandson Barry Mower recalls. “It was that bad.” It’s hard to imagine, looking at the river today.The passage of 30 years — and stricter waste discharge laws — have dramatically improved the Androscoggin, say state environmental experts and others who monitor the river.

“It’s the best I’ve ever seen it,” maintains Mower, who grew up not far from the river, in Greene. Today, at age 50, he works as a biologist for the state Department of Environmental Protection’s land and water quality bureau.

It may be, Mower says, that the Androscoggin is in its best condition this century.

Discharges from pulp and paper mills — historically the greatest polluters of the river — are way down, 95 percent less than 25 years ago. Almost all towns and cities are treating the sewer water they dump into the river, sometimes processing it twice.

Discharges from pulp and paper mills — historically the greatest polluters of the river — are way down, 95 percent less than 25 years ago. Almost all towns and cities are treating the sewer water they dump into the river, sometimes processing it twice.

For decades, fish couldn’t live in the river. They couldn’t breathe. The organic waste that polluted the Androscoggin ate up all of the oxygen at a depth of five feet. Today, almost the entire river meets the state-required minimum of five parts oxygen per million parts of water. Six and a half is the average.

Conditions have improved so much in the Androscoggin that the state is restocking it with fish. Last year, biologists from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife put 9,000 brown trout into the river between Rumford and the New Hampshire state line.

Mower thinks the state, mills, and municipalities are “very, very close to solving the whole problem” of organic waste polluting the river.

Other serious problems continue, however.

The Androscoggin “has the highest dioxin level of any river in the state,” Mower says. Dioxin is a by-product of the process mills use to bleach the paper they make and is known to cause cancer in humans.

The elevated dioxin levels aren’t surprising, Mower said, given the number of paper mills in proportion to the length of the river. Snaking 174 miles from lakes in eastern New Hampshire to Merrymeeting Bay near Brunswick, the Androscoggin is Maine’s third-longest river, behind the St. John and the Penobscot. Along its length are three bleached-kraft mills, which use and discharge massive amounts of water during operation. (The term “kraft” refers to a particular method of pulp processing.)

Last year, the Maine Legislature directed paper mills to take steps so that fish downstream of a paper mill will have no more dioxin than fish upstream. The mills have until the year 2003 to meet that standard.

Mercury levels in the water are another issue, one that’s not restricted to the Androscoggin. It’s a problem statewide, DEP officials say.

Utilities in the Midwest and waste-to-energy incinerators in southern New England belch the poisonous mercury from their smokestacks into the atmosphere, which carries it to Maine. It rains into lakes, streams, and rivers, where it contaminates fish and then poisons eagles, loons, and other birds that eat the fish. In fact, Maine has the highest levels of mercury in loons in North America, according to the DEP.

Utilities in the Midwest and waste-to-energy incinerators in southern New England belch the poisonous mercury from their smokestacks into the atmosphere, which carries it to Maine. It rains into lakes, streams, and rivers, where it contaminates fish and then poisons eagles, loons, and other birds that eat the fish. In fact, Maine has the highest levels of mercury in loons in North America, according to the DEP.

Because of the mercury threat, all Maine inland waters carry fish advisories now. For the Androscoggin, the danger also includes dioxin and the carcinogen PCB. The state advises against eating more than six meals per year of fish from the river; pregnant women should avoid river-caught fish altogether. The Androscoggin was the first Maine river to get such an advisory, in 1985.

Mercury and dioxin may be the Androscoggin’s biggest pollution issues for the future, says Paul Mitnik, a DEP water-quality specialist.

With the improvements the pulp and paper mills have made in treating their wastes, Mitnik says it would be “a hard call” to point to the river’s chief polluter now.

“All the point sources are really doing pretty well,” he says. Nonpoint sources of pollution — runoff, for example — are hard to pinpoint. “Nobody has the data,” Mower says.

What’s long been known, however, is that the river was seriously polluted.

“We knew a century ago there were problems on the Androscoggin,” Mower says. The public, however, viewed the problem as an acceptable trade-off for the jobs the pulp and paper mills provided.

“Pollution seems an inevitable, if ugly, reality,” Edmund Muskie ’36, then a U.S. senator, wrote in his 1972 autobiography, Journeys. Born in the mill town of Rumford, Muskie grew up on the Androscoggin.

In the 1940s, though, the tide of public thinking began to turn. A lawsuit resulted in a court order, putting the Androscoggin under the jurisdiction of Walter Lawrance, the Bates chemistry professor who became known as “The River Master.”

Lawrance worked with the paper companies to try to eliminate the pulp wastes, but a decade passed with little real improvement to the water quality.

In Muskie, though, the issue percolated. Appointed to a special Senate subcommittee, he helped craft and steer amendments to the federal water pollution control act in 1972. The legislation, now known as the Clean Water Act, required all industry and municipalities to treat properly their organic waste by 1972.

“That really was the beginning of the modern era, not too long after the first Earth Day” in 1970, Mower says.

Recently, the federal Environmental Protection Agency promulgated a set of rules further restricting the amount of waste mills may discharge into the air and water. Those will go into effect in 1999.

Over the last 22 years, the mills on the Androscoggin have cut the amount of waste they discharge from 300,000 pounds a day from each mill to between 4,000 and 5,000 pounds a day, Mower says.

No longer are there “big floating piles of sludge and wood fibers buoyed up by the gases,” he said. The “sludge” was a combination of biological solids and dissolved organic matter.

“The amount of material the mills discharge is now even less than the state would allow,” Mower notes. And he says it is processed or treated more intensely now before going into the river.

Likewise, towns and cities are, in general, more cooperative with the state’s effort to clean up the river, Mitnik says.

“We’re a team now, rather than at odds with each other,” as was the case a decade ago, he said.

The river’s not out of the woods yet, though. Even with the technological advances, it’s still polluted enough at times that the state advises people against swimming in it from Lewiston south.

Like many communities, Lewiston and Auburn still have networks of underground pipe that serve as both stormwater drains and sewer lines. After hard rains, the lines fill and send more water to the treatment plant than it can handle. The result: the untreated water pours into the river. To fix the problem, Lewiston and Auburn propose to spend a total of $45 million, Mitnik says.

Mitnik said the length from Lewiston to Brunswick is the only stretch of the river where overflows make the water unsafe for swimming.

Mower said the state’s efforts to clean up the Androscoggin may even be stronger now than when the campaign began a quarter of a century ago.

“We have a little bit left to do,” he says. Even so, “it’s a whole lot better now.” His grandfather would hardly recognize it.