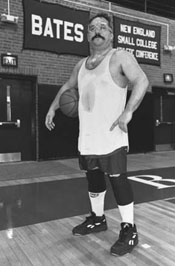

Hoop Dreams

Story and Photos by Marc Glass ’88If you’re Jewish and die in Lewiston-Auburn, don’t expect a noontime burial.

Story and Photos by Marc Glass ’88If you’re Jewish and die in Lewiston-Auburn, don’t expect a noontime burial.

“I don’t schedule anything between noon and 2 p.m. if I can help it,” said Rabbi Douglas Weber of Auburn, one of the most enthusiastic players of noontime basketball at Bates. “If a person can have their funeral at 10 a.m., and if it doesn’t matter to the family if we do it at 10 a.m. or we do it at noon, well, of course, I’ll say we’ll do it at 10 a.m.”

Weber’s priorities aren’t unusual among devotees of Bates noontime basketball, a highly spirited, play-to-13, call-your- own-fouls, full-court game played daily in Alumni Gymnasium.

The Bates game can be a study in contrasts from noontime basketball played at colleges, community centers, and YMCAs across the country. College employees and their guests are welcome to participate — regardless of talent — provided that they have the right temperament for the Bates brand of pick-up.

“The hallmark of civility in Bates noontime basketball is that people continue to pass me the ball,” said Weber, who considers himself the “worst player” of the game despite being a regular threat from three-point land. “It’s civil of other players not to yell at me for doing both stupid and untalented stuff.”

Weber, also an associate chaplain at Bates, said that there’s no eye rolling about anyone’s lack of court savvy (if traveling were called, they would never get a game to 13 points in an hour.) Rather than electing captains to choose squads — often an ego-crushing experience for those routinely picked last — the players size each other up and sort themselves into competitively balanced teams. Rookies who talk trash, bitterly contest fouls, and vent frustration by slamming the ball receive a quiet but firm lesson in behavior modification.

“Joe (Pelliccia) from time to time has been policeman of the game if the consensus in the locker room is that someone displays an uncivil tongue,” Weber said.

Pelliccia, associate professor of biology, and Bill Matthews, the Alice Swanson Esty Professor of Music, are considered by their teammates as among the “elders” and, therefore, stewards of the game. But the respect they’re accorded is due neither to tenure nor to endowed professorship.

“Any hierarchy that exists is strictly based on a sense from the other players that these guys are fair-minded and level- headed,” Weber said.

In many ways the style of the Bates noontime game is the College ethos writ large. Aside from the unrelenting politeness, team effort rather than individual achievement is valued (there’s almost too much passing), and professional personas disappear on the Alumni Gym floor. (The regulars read like the opening line of a joke: Did you hear the one about the lawyer, the farmer, the firefighter, the FedEx driver, and the anthropology professor?)

“I don’t see a professor, or a rabbi, or a lawyer,” Pelliccia said. “I see the guy who’s open for a pass, the guy who likes to go inside, or the guy who can drain them from 25 feet.”

These are basketball junkies, and their devotion to the noontime game is more than just a need to get the heart rate up an hour a day. Pelliccia, on leave at the National Science Foundation for the last two years, spoke wistfully of having to drop noontime basketball and take up jogging while away. “I missed the camaraderie.” Tom Foley, in his touching tribute to the late Bob Branham, a noontime regular and rhetoric professor at Bates, said his friend loved basketball because he “loved the idea of being a teammate” as well as “the jovial, rude, hilarious, and affectionate spirit of the game as played by true amateurs.”

Bates noontime basketball, though democratic and courteous, is not for the dilettante. Court time is coveted. Woe to those who dare to schedule Pelliccia for a lunch meeting. (He admits that noontime basketball is the highlight of his day). Weber is convinced that some of his faculty teammates at Bates willingly choose to teach unpopular 8 a.m. classes so they can be free for noon games.

Like the College itself, egalitarianism and competitiveness complement each other on the noontime court. No one throws chairs about losing, but nobody likes it much either. The blown knees, jammed fingers, sprained ankles, and even the occasional black eye aren’t always due to clumsiness. (Just ask Karen Kothe, assistant dean of admissions, who broke and dislocated her left index finger while blocking a pass two years ago.)

Women’s soccer and basketball coach Jim Murphy ’69 “will play against me at a certain level until I score on him,” said Pelliccia. “Then he ratchets it up. He’ll score a couple quick baskets against me just to put me in my place.”

“It’s tough if the game’s 12 to 11, let me tell you. You’re not going to get an inside shot,” said Murphy, rumored to be the most competitive player. “They’ll be hacking the living daylights out of you, making sure you don’t get an easy basket.”

Two years after graduating from Bates, Murphy, whose draft number was 34, found himself in the Army stationed at West Point. In his 18 months serving as a specialist-4 military police officer, he stayed fit playing the Army brand of noontime basketball, in which being “all you can be” was gospel on the court.

“There was no egalitarianism at West Point. There were wars on the courts. If you lost you didn’t stay on to play,” said Murphy, who considered himself a lesser player among the platoons of former collegiate players from places like Kansas, Villanova, and Indiana.

Weber couldn’t find the right balance of equality, civility, and competitiveness before joining the Bates game. At James Madison University, though etiquette and anti-clubbishness prevailed, the faculty players lacked commitment: “Some wouldn’t show up because they said they had to meet with students or finish an experiment. They let their work get in the way of the game,” he quipped.

At a YMCA in Elyria, Ohio, Weber found the game long on egalitarian spirit (an even mix of professionals, blue-collar auto-plant workers, and the homeless comprised the teams), but painfully short on courtesy. “The games were so competitive they degenerated into brawl ball,” he said.

Seeing those white and garnet NBA (Noontime Basketball Association) jerseys worn with pride by all players, the casual observer might dismiss the over-the-hill gang at Bates as taking themselves a bit too seriously. (Indeed, one jersey — belonging to 10-year veteran Robert Mullen — has been “retired.” Mullen, a former attorney with Linnell, Choate and Webber of Auburn, chose to forgo the Bates noontime basketball for a rewarding career on the bench when he was named a district court judge in August 1996. “It’s a statement of ennui that no one has pulled it down in two years,” said Mullen of his jersey that now hangs from a steampipe in the visitors locker room in Alumni Gym.)

The jerseys, it turns out, were actually a gift from Suzanne Coffey, director of athletics, to the noontime regulars, many of whom contribute annually to the College’s scholarship endowment as a token of their gratitude for a place to play.

Alfred Frawley, a 15-year noontime player and an attorney with Brann and Isaacson in Lewiston, annually reminds his fellow off-campus compatriots to acknowledge the College’s generosity.

The donation “says thanks for allowing low-rent characters such as ourselves to join the Bates community periodically at noon,” wrote Frawley in a recent solicitation.

“I think she [Coffey] had an ulterior motive in providing us with the jerseys,” Pelliccia said. “We used to play shirts and skins, and I think the sight of those bellies running up and down the court finally got to her.”