It Takes a Village

At Pathfinder Village, Down syndrome isn’t the end of the world, but the beginning of precious life — thanks to Marian Mullet ’50Story and Photos by Phyllis Graber Jensen

Marian Mullet ’50 has planned this moment for weeks. At approximately 11 a.m., Lane and Terry Bettcher, a young husband and wife from Ohio, are due to arrive in a rental car from the airport. They will enter the small, red-brick schoolhouse and hand over their 7-year-old son to begin his new life as a citizen ofPathfinder Village, the world’s only residential community and research center for people with Down syndrome. As president and CEO of the private, not-for- profit community, Mullet, along with the school’s principal, will greet the family when the school doors swing open.But just as she is about to leave her historic Hood House office for the two-minute walk to the school, Mullet learns that an important Pathfinder benefactor is on the phone. Momentarily torn, she decides she can take the call and still have time to get to the school before the family does. But she misses their arrival at the schoolhouse by minutes.

Marian Mullet ’50 has planned this moment for weeks. At approximately 11 a.m., Lane and Terry Bettcher, a young husband and wife from Ohio, are due to arrive in a rental car from the airport. They will enter the small, red-brick schoolhouse and hand over their 7-year-old son to begin his new life as a citizen ofPathfinder Village, the world’s only residential community and research center for people with Down syndrome. As president and CEO of the private, not-for- profit community, Mullet, along with the school’s principal, will greet the family when the school doors swing open.But just as she is about to leave her historic Hood House office for the two-minute walk to the school, Mullet learns that an important Pathfinder benefactor is on the phone. Momentarily torn, she decides she can take the call and still have time to get to the school before the family does. But she misses their arrival at the schoolhouse by minutes.

Mullet does not take her absence lightly. Concerned, she intercepts the Bettchers as they deposit Luke’s belongings — his clothing and stuffed animals — in his new residence. Mullet talks warmly with the Bettchers as they cross the community’s central quadrangle. By noon, the couple is seated for lunch at the Meeting House dining room. A welcoming team of Mullet, the school principal, the village program director, and the director of the Kennedy-Willis Research Center has gathered to cushion the difficulties of the day with support and information. After the meal, a satisfied Mullet evaluates the morning. She has been able to address important financial matters by telephone andoffer emotional sustenance to a family on the doorstep of major change.

“You have to run a business, but you have no business running a business unless you know where your heart is,” she says. “We give as much direct, intense love as possible, but we’re professional. You can’t do it just by loving someone.”

Marian Mullet means business. Marian Mullet is all heart. This yin and yang merger has enabled her to create an independent life for 86 Down syndrome residents, ages 6 to 60, at Pathfinder Village in Edmeston, N.Y.

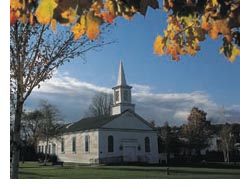

Drive along the two-lane Route 80 through the cornfields of this economically depressed but scenic dairy heartland 15 miles west of Cooperstown, and you’ll encounter a mirage of sorts: a picturesque 170-acre colonial village reminiscent of Williamsburg, Va., or Sturbridge, Mass.

We’re not talking “institution” here. Mullet bristles at the word and its dreary connotations. First and foremost, the two- dozen buildings of Pathfinder Village are a community where residents learn, work, and pursue a wide variety of recreational activities, “where each life finds meaning,” according to the village philosophy. Caring, independence, and integration into the greater community are absolute necessities, says Mullet, as are friendships and love affairs. Pathfinder residents have it all, and that’s a giant leap from the social ostracism at birth once faced by Down syndrome people.

The most common form of mental retardation — present in one out of 800 births — Down syndrome is a chromosomal disorder that occurs shortly after fertilization and results in a variety of physical and mental characteristics such as distinct facial features, physical impairments, and delayed mental development. Although scientists didn’t understand the genetic causes of the disorder until the 1950s, an English physician, Langdon Down, first described the disability in 1866. Only in the last third of this century did the medical or social service communities respond with humane, practical arrangements for a Down syndrome child.

“Down syndrome isn’t the end of the world — it’s the beginning of precious life,” Mullet says. “With the right programs and lots of love, a child born with Down syndrome can experience joy and the satisfaction of school and work — just like the rest of us.” Mullet defines a humane approach by setting individual goals and charting an independent path. The village’s name was inspired by the fictional woodsman Natty Bumpo, the Pathfinder in James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, two of which chronicle the development of 18th-century Cooperstown.

“Down syndrome isn’t the end of the world — it’s the beginning of precious life,” Mullet says. “With the right programs and lots of love, a child born with Down syndrome can experience joy and the satisfaction of school and work — just like the rest of us.” Mullet defines a humane approach by setting individual goals and charting an independent path. The village’s name was inspired by the fictional woodsman Natty Bumpo, the Pathfinder in James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, two of which chronicle the development of 18th-century Cooperstown.

Mullet’s commitment to Pathfinder Village began in 1963, when she and her husband, Frank ’47, moved to the central New York hamlet where he took on the district school superintendentship. Though fully engaged with raising four children and breeding Irish setters, Mullet used her training as a registered nurse — she was a member of the last Bates nursing class — to volunteer as nursing supervisor at the local Otsego School, a facility for 60 Down syndrome residents, children and adults who “were literally raised behind a fence,” she remembers. “Love and care were there, but true opportunity to grow physically and mentally were nonexistent.”

By 1976, Mullet was a paid Otsego employee, but the school faced extinction in the wake of a state-mandated revolution in the treatment of the mentally retarded (see sidebar). Choosing to live or die, the school’s new board opted for life by investing its confidence in an untested but capable Mullet as executive director. Knowing she had rocked many of the Otsego residents in her arms as infants, they were confident of her commitment. Yet, were any of the board members prescient enough to predict just how wildly successful the homemaker would be in converting a tiny school into an internationally recognized, multimillion-dollar residential village and research center? “I think the board took a terrible chance with me,” she says looking back. “We formed a whole new organization out of a corn field. I grew this baby.”

“Marian Mullet is not an empire builder. She simply feels she did what had to be done to help her friends,” wrote her younger brother Stephen Goddard ’63 in a 1988 New York Times op-ed that appeared the day she received an honorary doctorate of laws from her alma mater. “Bates was a teething ring in our house,” said Mullet on a recent visit to Bates, where she donated a family memoir of her father, Harvey B. Goddard ’24. (Her brother Harvey Goddard ’51 also attended Bates.)

Pathfinder Village is Mullet’s answer to what she calls “the greatest curse of mental retardation — loneliness.” Seven- year-old Luke Bettcher’s parents, Lane and Terry, chose Pathfinder Village as their answer. The parents of three children, they struggled with their son’s increasingly unmanageable behavioral difficulties. The child also exhibited a mild form of autism. The Bettchers undertook an exhaustive two-year search for solutions to their heartache, and like countless others, discovered Pathfinder Village on the Internet. Steeling for the worst, they instead found themselves wowed by the consistently rave reviews from parents, lawyers, and the state board of education. “This is a unique place,” Lane Bettcher says. “It doesn’t exist anywhere else. Pathfinder Village was the first place I’d been where the place was much better than the brochure.”

The village concept arose, says Mullet — a niece of one of the original Williamsburg architects — from trying to recreate the cohesiveness of early American life, providing “a very free environment where people can come and go at will, where neighborliness and friendship count, where you don’t have to ask permission to do things.”

Poised to combat what Mullet labels “poisonous dependency,” Pathfinder Village educates its youngest residents and finds employment for adults — based on their abilities to function — in surrounding communities. Terry Bettcher says it simply: “My main hope for Luke is the same as it is for my other children: to be happy, to be productive with something to do every day. We can’t provide him with that. Here, they can. That’s why we’re here.”

Darlynne A. Devenny is there for an altogether different reason. During a brisk aerobic stroll around the Village Green on a late fall afternoon, she encounters a variety of friends. Some stroll in pairs, others chat together on one of many benches donated by the Rotarians. Still another walks Thunder, a 5-year-old Irish setter and resident of Susquehanna House. A developmental psychologist in life-span studies for the state of New York, Devenny has spent the last eight years studying the effects of aging on language and memory in the mentally disabled, many with Down syndrome, ages 18 to 25. Among other sites throughout New York, she visits Pathfinder Village two weeks a year, two days at a time, as part of her 15-year funded investigation. “I have been to many places I think are wonderful and successful,” Devenny says, acknowledging a variety of positive approaches to Down syndrome, such as group homes or independent living made possible by community support. “But the atmosphere at Pathfinder Village is very special. There’s a calmness here,” she says.

Like many others, she credits Mullet with the difference. “I consider Marian Mullet to be a visionary who acts on her visions.” And never before, says Devenny, has she encountered a residential setting where research plays such a central role.

The recently completed $1.5-million Kennedy-Willis Center represents Mullet’s most ambitious step, one she sees as crucial to Pathfinder’s outreach mission to provide help for those seeking hands-on education, direct counseling, and research resources on Down syndrome and related developmental disabilities. “It is inspiring to be able to make a plan and see it through to its last goal. Few people have had so much pleasure,” Mullet says.

The recently completed $1.5-million Kennedy-Willis Center represents Mullet’s most ambitious step, one she sees as crucial to Pathfinder’s outreach mission to provide help for those seeking hands-on education, direct counseling, and research resources on Down syndrome and related developmental disabilities. “It is inspiring to be able to make a plan and see it through to its last goal. Few people have had so much pleasure,” Mullet says.

Although Pathfinder’s Facility Services and programs bear Mullet’s imprint, the place functions as a collective effort. Ask parents what’s best about Pathfinder, and they’ll answer promptly: “The staff.” Ask Mullet and staff the same question, and their answer is as predictable and swift: “The residents.” Are those with Down syndrome generally happy and loving? Mullet replies: “They don’t get confused with your status, education, money, and good looks. They judge character, and that’s the most honest assessment of humanity I know.” In personal ways, Mullet’s life is intertwined with Pathfinder Village. When the Mullets’ youngest son, Tom, died of cancer in 1989, the schoolhouse bell was named in his honor. “When the bell tolls, it’s ringing for Tom,” she says. “This is not a job, it’s a life.”

With ultimate pride, Mullet points to Pathfinder’s debtless financial picture, grounded in the Yankee (and Bates) tradition that says you raise funds before you build anything. She’s never put up a building she didn’t pay for first; cash in hand “maintains my peace of mind,” she notes. “We’re like a small college. If you don’t continually fund raise, you’re soon not there.” Mullet values her relationships with residents’ families, both for insuring their peace of mind and assuring their roles as Pathfinder benefactors. “My responsibility here is to see every family here has a comfort level. Everyone gives to charity. They might as well give to us.”

It’s hard to say “no” to Mullet. James Seitz, Pathfinder Village director of development and public affairs, couldn’t. “What a sweet little old lady,” he thought to himself upon first hearing her voice on his answering machine eight years ago. Today, Seitz marvels at the “sweet little old lady’s” effectiveness as a fundraiser and administrator. “This is not her job. It’s her passion,” he says. Often on the road with Mullet at fund-raising events, he has watched her work the crowds of Rotarians (Mullet was named the “Woman Who Contributed Most to Children” by the district Rotary International in 1998) and others. “It’s not what she says,” Seitz reports. “It’s how she says it. She’s got millions of stories, and her vision comes right from the heart.”

Although she no longer phones her staff from the road, Mullet still travels with a fax machine. “Pathfinder Village is her baby. She makes sure her baby is taken care of,” Seitz says.

Pathfinder parents enjoy peace of mind because their babies are taken care of. As recently as 25 years ago, Down syndrome children faced state institutionalization or stigmatization at home. “Those were the days when people hid such children in the closet,” remembers Thomas Schaeffer, a retired surgeon. Recently, he and his wife, Genevieve, arrived for a three-day visit with their 33-year-old-son Michael. The Johnstown, Pa., couple brought friends along to show off Pathfinder Village and admire the surrounding blaze of autumn. When the foursome appeared, Mike immediately shouted “The Inn!” where he bunks with his folks for their stays. A low-functioning resident, Mike performs simple tasks in a nearby sheltered workshop during the day. He is happy, but his adjustment was some time in coming.

In 1965, the Schaeffers reeled in shock at learning they had a Down syndrome baby. Urged by family, friends, pediatrician, and clergyman, the couple painfully decided to institutionalize their infant at birth. Just before the placement was to be made, Schaeffer found himself in the hospital nursery feeding his 10-day-old son when his wife suddenly declared, “Bullshit! What are we here for?” The neonatal nurses cried and cheered when the pioneering parents decided to take their son home for good, he says, his own voice catching at the memory. With five siblings at home, Mike enjoyed family life until his brothers and sisters finally departed. Ultimately, the depressed young man was hard pressed to get out of his pajamas. But one day, his father stumbled across a small ad for Pathfinder Village in a magazine about the developmentally challenged, and Mike’s future was born.

Mullet cuts a wide swath, whether she’s clearing a corn field or handling administrative challenges. Tied to many of the adult residents since they were infants, she maintains affectionate relationships with these same individuals, but at a distance, as she cruises, not unlike a missile — with a payload of peace — from one mission to the next. No detail escapes her notice. During an early-morning breakfast, she spies an extinguished light bulb in the dining room and immediately points it out to a staff member. Later in the day, she notices a frayed corner on the doormat at the Chapel’s entrance and makes a mental note. Pathfinder Village looks breathtakingly pristine thanks to Mullet’s devotion to the smallest detail. Like a major-league hurler with just one pitch — but a very good one — Mullet challenges problems with her best stuff. She’s “incredibly one-pointed” says another staff member. “She’s the mayor of the town and she wants it to be a really good town.”

Marian does enjoy a life outside of the village (the Mullets live nearby), yet in order to truly relax, she and Frank must leave town, as weekends in Edmeston are often spent meeting with visiting parents. She is happy to accompany Frank to Florida for part of January and February each year, but she then heads back to Pathfinder while he — a golfer — remains down south for the winter’s duration. Frank considers their marriage “a complete life.” For more than half their married lives, he worked and she supported him in his career. Now, the tables have turned. “We’ve both had the opportunity to do things we felt were important. She’s helped me in many ways, and I hope I have been as helpful to her,” he says, adding dryly, “But she doesn’t need any help.”

Mullet may hold the reins, but there isn’t much vanity involved. According to Paul Donnelly, director of the Kennedy- Willis Center, “she is to Pathfinder Village what Walt Disney was to Disney World.” But you’ll notice, he mentions, that the place isn’t called Mulletsville. The board named the gymnasium after her, but she promptly hid the sign under her bed, Donnelly says.

Midafternoon, Lane and Terry Bettcher stop by Mullet’s office to say goodbye. There will be no lingering. Although today is not the emotion-filled day the parents faced months ago when they actually made the decision to send their son away from home, Mullet knows just how tough it must be. His mother and father will not see Luke for a month as he makes the initial adjustment to his new surroundings. It will be a stressful time for the parents, Mullet points out, but not for the village staff. “We make them our own immediately,” she says. “Take good care of him,” Terry beseeches. “As a mother, I just have to say that.” Although confident of Pathfinder’s ability to educate her son, she still worries who will tuck him in that first night and read him Good Night Moon.“We can’t take your place,” Marian reassures her. “But we’ll be thinking of you.”

At 8 a.m. the following foggy, misty morning, the school house bell peals, signalling the beginning of a new day. Residents stream down the walkways: adults headed for work, children for the little brick schoolhouse. In his customary position, principal Don Drake stands outside the front entrance, umbrella aloft, as he greets students and lights up the gray, wet sky with heartfelt pleasantries. Among the stream of walkers, Luke Bettcher suddenly appears, hand in hand with Ken Whiteman, the school physical education teacher and scout leader. The boy has enjoyed an easy night in his new home and looks into Drake’s eyes when addressed. There is a smile on Luke’s face and a full life on his horizon.