Object Lessons

Bates professors explain the objects of their affections

Photos and introduction by Phyllis Graber Jensen

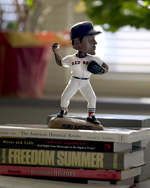

Late one afternoon, camera bag slung over my right shoulder, I stopped by my husband’s first-floor office in Pettengill Hall. As he wrapped up his business before heading home, I sat idle and restless. Eventually, my eyes wandered to a bobble-head doll of Boston Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez placed on a stack of books and periodicals. I’m no Boston fan (forgive my New York City pedigree) but the lovely window light caressing Pedro caught my eye. Out came a camera.

Late one afternoon, camera bag slung over my right shoulder, I stopped by my husband’s first-floor office in Pettengill Hall. As he wrapped up his business before heading home, I sat idle and restless. Eventually, my eyes wandered to a bobble-head doll of Boston Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez placed on a stack of books and periodicals. I’m no Boston fan (forgive my New York City pedigree) but the lovely window light caressing Pedro caught my eye. Out came a camera.

When I printed one of the photographs, it struck me: This picture tells a story of Hilmar Jensen, associate professor of history. And if I went into any other faculty office — practically at random — I could probably capture a scene that would open a window on the soul of its occupant.

Hence this series of still-life photographs, accompanied by responses to a question posed by this amateur anthropologist (or nosy neighbor): What chapter of your life story does this scene tell? The resulting photographs give eight Bates faculty members a chance to share with you a bit of the visual “here I am” that they share each day to students and colleagues who stop by their offices.

Click on any of the thumbnails below for larger images.

Kirk Read, Associate Professor of French, Hathorn Hall, Room 307

That grinning kid at the center-bottom is me. At about that age my mother began taking my brother and me into New York City from rural upstate to show us the wonders of Manhattan, where she had worked in skyscrapers as secretary to the captains of industry. Much of this memorabilia was in place before 9/11 and I keep it there in defiance, especially the marvelous photo by Margaret Bourke-White of the gleaming airliner gliding gently past the Chrysler Building. In the lower right is a vintage brochure for the Empire State Building. Imagine my surprise to learn that the couple posing in the middle are the parents of my colleague Mary Rice-Defosse on their honeymoon! It gives me hope that there is still wonder and magic to be revealed in this city of my youth to which I faithfully return with my own eager children.

That grinning kid at the center-bottom is me. At about that age my mother began taking my brother and me into New York City from rural upstate to show us the wonders of Manhattan, where she had worked in skyscrapers as secretary to the captains of industry. Much of this memorabilia was in place before 9/11 and I keep it there in defiance, especially the marvelous photo by Margaret Bourke-White of the gleaming airliner gliding gently past the Chrysler Building. In the lower right is a vintage brochure for the Empire State Building. Imagine my surprise to learn that the couple posing in the middle are the parents of my colleague Mary Rice-Defosse on their honeymoon! It gives me hope that there is still wonder and magic to be revealed in this city of my youth to which I faithfully return with my own eager children.

Trian Nguyen, Luce Junior Professor of Asian Studies and Assistant Professor of Art and Visual Culture, Olin Arts Center, Room 314

The model of the Borobudur Stupa is a souvenir given to me by the abbot of Mendut Temple when I visited Java in July 2002. With the support of a faculty grant, I visited the important stone religious monuments in Indonesia to collect visual materials for my courses.

The model of the Borobudur Stupa is a souvenir given to me by the abbot of Mendut Temple when I visited Java in July 2002. With the support of a faculty grant, I visited the important stone religious monuments in Indonesia to collect visual materials for my courses.

The temple complex is one of the greatest monuments in the world and at one time it was a spiritual center of Buddhism in Java. Composed of 55,000 square meters of lava rock, the monument was erected on a hill in the form of a stepped pyramid of six rectangular stories. The stupa has three circular terraces and a central stupa at the top surrounded by 72 small ones. The stupa is rich with sculpture and galleries in high relief. The structure conveys narrative illustrations of the law of karma, scenes from the previous lives of the Buddha, and the spiritual path to achieve enlightenment. The monument could also be considered as an open stupa, a large mandala, and the Buddhist cosmic world view. Indeed, I felt deeply humble when visiting this glorified monument of the Buddhist world.

It was an unforgettable experience for me to climb to the top of the stupa before dawn to see the sunrise. It was the best hour of the day. I felt everything around so tranquil and experienced the mysterious power generated from the stupa. It was immense, incomprehensible, yet so fascinating.

Elizabeth Eames, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Pettengill Hall, Room 159

Mud-cloth of customary West African design—given to me by colleagues—provides a fitting backdrop for this artful radio, purchased by me personally from a street vendor working for Streetwires, a so-called “community upliftment project” in Cape Town, South Africa. While my long-standing research interest lies with the market traders of southwestern Nigeria, South Africa always fascinated me; hence I was thrilled to lead a recent CBB Cape Town semester, where I collected this piece of tourist art.< At a small liberal arts college such as Bates, I get to teach a broad range of subjects, everything from comparative economics to “Cinematic Portraits of Africa,” figuratively traversing an entire continent in the process. Fundamentally, though, all courses seek a critical understanding commodification.

Mud-cloth of customary West African design—given to me by colleagues—provides a fitting backdrop for this artful radio, purchased by me personally from a street vendor working for Streetwires, a so-called “community upliftment project” in Cape Town, South Africa. While my long-standing research interest lies with the market traders of southwestern Nigeria, South Africa always fascinated me; hence I was thrilled to lead a recent CBB Cape Town semester, where I collected this piece of tourist art.< At a small liberal arts college such as Bates, I get to teach a broad range of subjects, everything from comparative economics to “Cinematic Portraits of Africa,” figuratively traversing an entire continent in the process. Fundamentally, though, all courses seek a critical understanding commodification.

Bonnie Shulman, Associate Professor of Mathematics, Hathorn Hall, Room 204

This small corner in my office includes a framed copy of my first recognition as a scientist (I was 9 years old) or rather as a “Future Scientist of America.” I was very proud of that certificate, and still am! Beneath is a stack of books ready to be “filed” — either returned to their shelves or given away (maybe put on the Bates “forsale” listserv?). It shows some of my interests — in applied mathematics, teaching mathematics, women’s studies, and science fiction, especially feminist science fiction. There are also a couple of videos I use in classes and with the student group SWIMS (Society for Women in Mathematics and Science) which I advise — including a copy of the classic movie Madame Curie with Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon, which inspired a generation of young women (including me) to stick with science and math.

This small corner in my office includes a framed copy of my first recognition as a scientist (I was 9 years old) or rather as a “Future Scientist of America.” I was very proud of that certificate, and still am! Beneath is a stack of books ready to be “filed” — either returned to their shelves or given away (maybe put on the Bates “forsale” listserv?). It shows some of my interests — in applied mathematics, teaching mathematics, women’s studies, and science fiction, especially feminist science fiction. There are also a couple of videos I use in classes and with the student group SWIMS (Society for Women in Mathematics and Science) which I advise — including a copy of the classic movie Madame Curie with Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon, which inspired a generation of young women (including me) to stick with science and math.

Emily Kane, Professor of Sociology, Pettengill Hall, Room 269

One of the things I enjoy most about teaching at Bates is the opportunity to construct relatively loose boundaries between work and home. Though we live some distance from campus, I bring my 10-year-old twins to campus as often as I can, and some of the images in this picture represent those visits. My family always accompanies me to Commencement, and the cute little creature at the center of this picture is one my child Aaron drew on the morning of Commencement 2004. Along the blackboard’s borders are various drawings that Aaron and his twin brother, Samuel, have made over the years, including frogs, butterflies, Pokemon characters, and even the elusive Snark they learned about by attending the Robinson Players’ presentation of The Hunting of the Snark. The words “Emily Rules,” decorating the top of the board, were added by a Bates student, as a surprise when I was out of the office. Bates students are generous with compliments to the faculty, but this one struck me — from a faculty perspective — as an unusually-phrased accolade, and I couldn’t resist leaving it up on the board.

One of the things I enjoy most about teaching at Bates is the opportunity to construct relatively loose boundaries between work and home. Though we live some distance from campus, I bring my 10-year-old twins to campus as often as I can, and some of the images in this picture represent those visits. My family always accompanies me to Commencement, and the cute little creature at the center of this picture is one my child Aaron drew on the morning of Commencement 2004. Along the blackboard’s borders are various drawings that Aaron and his twin brother, Samuel, have made over the years, including frogs, butterflies, Pokemon characters, and even the elusive Snark they learned about by attending the Robinson Players’ presentation of The Hunting of the Snark. The words “Emily Rules,” decorating the top of the board, were added by a Bates student, as a surprise when I was out of the office. Bates students are generous with compliments to the faculty, but this one struck me — from a faculty perspective — as an unusually-phrased accolade, and I couldn’t resist leaving it up on the board.

Hilmar Jensen, Associate Professor of History, Pettengill Hall, Room 104

Baseball is the most intricately “historical” of American games. Not coincidentally, among the scores of modern American historians I’ve known over four decades in the profession, a disproportionate majority have been baseball fans of varying degrees of intensity.

The three bits of baseball memorabilia in my Pettengill office, therefore, evoke a shared sensibility — of accretions of diachronic awareness, of cultural “American”-ness, of disciplined playfulness, of over-commercialized nostalgia and kitschiness, and of intergenerational mutuality — among colleagues in my discipline, as well as among many students who visit. Two of the pieces — an old-style, home-team Phillies cap and a photograph of the inspiringly ageless hurler Nolan Ryan’s blazing fastball caught, breathtakingly, in mid-flight from the batter’s point of view — serve as visual clues and conversation starters as important to understanding who I am as the books and senior theses that line the shelves along each wall.

The bobblehead statute of Pedro Martinez, however, has little to do with such calculated intentionality. It was a Father’s Day joke gift from my wife and daughter that ended up in my office this past spring because there seemed no appropriate spot for it at home. I simply didn’t have the heart to throw it in the trash.

Carl B. Straub, Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies and Professor of Religion, 73/75 Campus Avenue, Room 11

Voltaire and Ambrose Bierce wrote dictionaries; I merely use them. This one, which I bought my first day in college nearly 50 years ago, (I remember the purchase in the Colgate bookstore), has been on my desks almost every day since. It has been my silent companion. It has yielded up secrets when I thought I knew it all; it has disciplined me when I was careless. It has reminded me that my own creative powers are strangely limited by our lexical fate. No wonder Bierce called a dictionary (not his!) “a malevolent literary device.”

Voltaire and Ambrose Bierce wrote dictionaries; I merely use them. This one, which I bought my first day in college nearly 50 years ago, (I remember the purchase in the Colgate bookstore), has been on my desks almost every day since. It has been my silent companion. It has yielded up secrets when I thought I knew it all; it has disciplined me when I was careless. It has reminded me that my own creative powers are strangely limited by our lexical fate. No wonder Bierce called a dictionary (not his!) “a malevolent literary device.”

The book is not about a chapter in my life but rather of a theme on my journey. The theme is awareness that words are dangerous when misused because they have so much power. They put persons and things in their places, constructing situations with which we must struggle. Words play havoc with our sensate selves, screening us from deep recesses of life, and thus seducing us into fickle and brittle pageants. My dictionary hasn’t saved me from these dangers. But its presence has kept me alert.