A Penney Earned

This profile of Shirl Penney was published in the summer 2005 issue of Bates Magazine. Since then, Penney has become the founder, president and chief executive officer of Dynasty Financial Partners, a transformational platform that allow financial advisers to operate independently from traditional firms.

Dynasty Financial Partners now has a network of advisers overseeing more than $100 billion in client assets. “Penney isn’t just a business leader. He’s a visionary, reshaping the independent wealth management industry,” notes a recent profile.

Not yet 29, Shirl Penney ’99 directs business development for Smith Barney’s Wealth Management Group, managing the group’s teams in 13 U.S. cities.

Penney grew up poor in Eastport, Maine, far Down East. For a stretch, he was nearly homeless — at night, he’d stop by the pizza shop at closing for a handout.

He’s a Bates graduate, but no Bates diploma hangs on his wall, and the reason involves his Commencement week, when he had to bury the man who raised him back in Eastport.

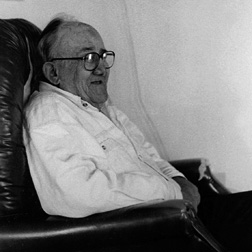

During Short Term my senior year, my granddad got double pneumonia, so I went home to take care of him. Then we found out he had cancer all through him. He must’ve known how sick he was, but he never told me because he didn’t want me to leave school. Soon he was on life support, and I had to make the decision whether to take him off.

I was a junior advisor and a resident coordinator, so I had gotten to know a number of the deans. So I called Dean Reese and said, “This would be a tremendous favor: Is there any way I can get my diploma early?” Like a lot of colleges, Bates just doesn’t hand out diplomas early. But I asked. I said it would be a great honor to have my grandfather at least see it before he passed away. Dean Reese got it done.

Penney’s story isn’t unique. Mainers from miniscule towns have defined Bates culture from the College’s founding. Just try to find Salem, Byron, Vienna, and Cornville — hometowns of students in the first Bates graduating class in 1867 — on a map.

I was raised by my step-grandfather, Clarence Townsend. We grew up on welfare — I’m not ashamed at all. In fact, I’m proud that we grew up on food stamps and his Social Security and whatever money I could make doing odd jobs. I had great teachers in Eastport. People in my community believed in me. So I’m a big believer that it takes a community to raise a child, and that community includes Bates. When I was in fifth grade, my grandfather’s home was condemned. They said it was not a place a child could live. Carpentry students chipped in to rebuild the house.

During that time, I lived with various neighbors. The local pizzeria guy, at 8 o’clock closing, would give me leftovers if I swung by. Little things like that helped us get through. When I was older, I cleaned salmon nets on an aquaculture farm; they get dirty with the dead fish, maggots. Really bad. I’d probably be doing that if I was still in Eastport.

Born to a teenage girl, Penney has never met his father. He graduated from Shead High School, total enrollment about 170, of whom a third are eligible for free lunch. The last census put Eastport’s unemployment at 15 percent (ranking it 478th out of 491 Maine towns), its median income at $23,488, and its average home price at $51,600. Penney is the only one in his family ever to have attended college.

It’s not uncommon, unfortunately, where I’m from: My mother was 15 or 16 years old when she had me. She was a child. My step-grandfather — my mother’s step-father — said he couldn’t live thinking that the baby might end up in an abusive home. He took me in. My biological grandmother and he had separated, so as a 58-year-old single man, who was not related to me, he raised me. No official adoption was really needed in the sticks of Maine.

He never made it past sixth grade. Severe birth defects affected his physical appearance. He went to work during the Depression so a few of his siblings — he was from a family of eight — could graduate high school. He worked hard doing manual labor his whole life and had nothing to show for it. He always said to me, “You can accomplish anything that you want, but I want you to go to college and never have to do manual labor.”

Growing up, Penney would tell people he wanted to work on Wall Street. “What’s that?” they’d respond. For Christmas, he once asked for a subscription to Money magazine. Each summer, he’d ask a tourist for copies of The Wall Street Journal. To pay for Bates, Penney took out loans and got scholarship aid. He also took campus jobs. He sold The New York Times. He went into Lewiston to secure eBay consignments. The most popular and infamous Bates T-shirt in recent student history — a spirited rebuke to a similar shirt worn by Colby students — had its genesis in Penney’s dorm room. He laughs.

That’s something that I’m not necessarily proud of! I did get into eBay very early. I bought a digital camera with money from the T-shirts and took photos of antiques in local shops to post on eBay. A silver candleholder set that I was able to consign for $100 sold for about $1,300. That paid the property taxes back home and some school expenses. My grandfather had a car accident my junior year; some good sales on eBay helped him buy a car.

Driving to work today, I was thinking about the value that Bates added to my life. Like meeting very smart kids at Bates from around the world and knowing I was at the top of the game in terms of the homework I’d done about the financial world. Building relationships with adults like Dave Moore in the mailroom, professors Carl Schwinn and Carl Straub, and Adam Levin in sports information. Traveling with the baseball team, being captain — a wonderful experience. Hanging out with international students. Some of us could not afford to go out to the movies or dinner so we would go to an on-campus movie or hang out at the Den. That was great, because cultural diversity was nil where I was from.

His first week at Bates, Penney visited the Office of Career Services. He interned through the Ladd program at the Portland office of Smith Barney his junior summer. That summer, Robin Hodgskin ’76, senior vice president, suggested that a colleague, Joe Mara, visiting the office from New York, interview him. “One of the great things about Shirl is he’s got a nice air of self-confidence — but not arrogance,” Mara recalls. “His whole life was a pathway to where he wanted to be. He takes in everything and builds upon it.”

I’m laughing about it now: When I interviewed with Smith Barney in New York, I went to the Salvation Army in Lewiston and bought a $13 suit. The legs were too short, it had a hole in the crotch, and the jacket didn’t fit. I borrowed a tie from my roommate and a pair of shoes from someone else on campus. I walked into the interview and said, “It’s kind of warm in here, isn’t it?” And immediately I took my jacket off because it didn’t fit.

Whenever I didn’t know or understand something I would ask a question. My mentorship has been by committee. I’d ask Joe Mara, “Look, how do you carry yourself in front of a billionaire?” Another colleague, Christopher Poch, taught me etiquette, from writing thank-you notes and hosting dinners to knowing what tie to wear with what suit and belt. He probably got tired of my questions, like if I should wear cufflinks or not, or if wearing them would potentially offend someone.

Penney entered Wall Street finance at the perfect time. Citigroup had been formed, with Smith Barney as one of its divisions. Wealth management — call it the liberal arts approach to handling client financial needs — was the buzzword.

Historically, the business had been primarily transactional — you’d call your stockbroker and he would help identify stocks and bonds that you should buy. While we had world-class niche players and capabilities within Citigroup, they were in silos and didn’t really work well together to support a client relationship. After I arrived in summer 1999, Joe and I started a group called Family Wealth Management to bring these resources together. In many ways it was the beginning of wealth management at our firm. Essentially, we try to simplify a client’s life by bringing together the different components of wealth management under one roof.

Mara allowed Penney, in just his second month on the job, to run part of a presentation for a Times-Warner executive. “Shirl was fabulous, as if it were scripted,” Mara says. “When the client raised a question, Shirl was absolutely in position to engage him professionally.”

The marketplace was changing, driven in part by new wealth. In late 2000 Chris Poch told a financial publication that “the newer high-net-worth individual is often younger, more aggressive, looking for performance, social activities and philanthropy to become part of their plan.” Working with Poch, Penney headed into the field to help start the firm’s Private Wealth Management group for clients with a level of affluence north of $50 million.

I was given an opportunity at a very young age to have access to all of the senior resources in all of Citigroup and to immediately go out and start meeting with some of our biggest clients. It was wonderful. Sink or swim. I helped open our New York office, then our LA office in 2000, and two years later the San Francisco office.

In 2005 Penney was appointed to his present position. “Exceptionally rare,” is how Robert Matthews, managing director and director of wealth management for Smith Barney, describes Penney’s abilities. “Not only does he possess a singular talent for applying holistic solutions to complex problems, but he is also masterful at building a team process to help other professionals determine their very best.”

All this, but no Bates diploma.

Bates FedExed the diploma to the hospital. My grandfather — I call him “Gramp” or “Papa” — was on medication, so he was kind of out of it his last week. I said, “Gramp, we did it. I graduated. I have my diploma here.” For the first time in days, his eyes opened immediately. He looked at the diploma, which is in Latin. I was crying but then started laughing and I said, “Don’t worry, Papa, I can’t read it either!” But I told him what it meant: It meant that we did it together, and that his love and faith in me paid off. I said, “I’m giving this to you because you sacrificed a lot more for this than I did.”

The next day I took him off life support, and the morning after, he died in my arms, at 8 o’clock. It was the day before my graduation. I gave the diploma to him, and he still has it. It was buried with him.