Moments from the 1960s to the 1970s

As Bates celebrates its 150th anniversary in 2005, we asked Bates people to share the moments that, despite the years, still dance in the mind.

College is often a time, writes contributor Peter Moore ’78, when you were “alive to every sensation, every idea, every person, every emotion.” So, these Bates moments aren’t the College’s marquee stories. Figuratively speaking, these are your travels, off the main road and more over hill and dale.

A Face in the Crowd

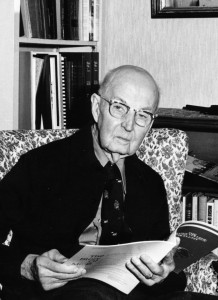

Harry Rowe, Class of 1912, the “Ichabod Crane-like figure” who comforted Peter Gomes ’65 in the Bates Chapel in 1961. Photograph courtesy of the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library.

A few hours after my arrival at Bates in 1961, the freshman class gathered in Alumni Gym, where Dean Lindholm and Prexy Phillips addressed us. The next day, Sunday, we all went to Chapel, where Dean Zerby preached. Directly afterwards, our parents were to leave. I stood outside the Chapel on Campus Avenue, making a brave show of farewell. I shook my father’s hand, kissed my mother, and then they drove off.

I went back into the Chapel to cry in privacy. There I saw a tall, spare, bald-headed man slowly picking up the litter in the pews. I took him to be a janitor. He noted my distress, and in a solemn but friendly voice said that I’d soon feel better about college. Later in the week I saw this Ichabod Crane-like figure again: Dean Harry W. Rowe ’12, with whom I would be friends for the rest of his life. At my most vulnerable moment, he was the human face of Bates.

The Rev. Peter J. Gomes ’65, D.D. ’96, Pusey Minister in The Memorial Church at Harvard and Plummer Professor of Christian Morals

Sweet Tidings

In 1979, when the Bates relationship with Morse Mountain was new, I organized an alumni tour of the new conservation easement. Led by Professor Bob Chute, we walked to the beach hearing about the marshes, porcupines, dunes, and dreams of what Morse Mountain could be for generations of Bates students. When we began the return trip, we were surprised to see the October tide covering the road and creeping around the running boards of the chagrined Professor Chute’s truck. The Archives has a photo of my husband giving a piggy-back ride to Doris David Brooks ’29 while the rest of us waded to Chute’s truck and prayed that it would start. Bob’s only comment: “Guess I’ll have to run this truck through the car wash.”

Sarah Emerson Potter ’77, director of the Bates College Store

First Impressions

When I arrived on the Bates campus as a very green 25-year-old to teach Cultural Studies in the fall of 1967, the clock was already ticking on Cultch and a host of other requirements and prohibitions, but nobody yet knew that. For the first program meeting, five much-younger instructors, all male, came to Charles Niehaus’s office in Hathorn. Someone, who could only have been Charles, handed out cigars. We lit up. We puffed. Then Charles leaned back and looked meaningfully at the three of us who were absolute novices, having just been hired: “It’s very important that you understand what Cultural Heritage is. It’s… It’s… Carl, you have some thoughts on that.” Indeed, he did. That was my real introduction to Carl Straub, who had arrived a couple of years earlier and already made his mark on hearts and minds. I didn’t yet know enough to teach anything well — let alone, everything —but I did then learn that I had come to the right place. — John R. Cole, Thomas Hedley Reynolds Professor of History

Cultch Following

More than 30 years after teaching it, others’ memories of Cultural Heritage continue to press upon me. These moments usually come in post cards from a traveling graduate. Here is a recent one: “Hello Professor Straub. I finally saw the Acropolis. Thanks to Cultch I really saw it.” Although the memory of Cultch lingers within the diaspora of its graduates, it is almost gone among those who dwell on campus. The hearty although transitory cluster of colleagues, that happy band who had the temerity to teach from Homer to Freud by way of Machiavelli, broke up decades ago, scattered to other earth-bound places. Some, like my friend Charles Niehaus, are dead. I no longer lament the passing of Cultch. At its best, Cultch attempted a broad, albeit selective and hence somewhat deceptive recitation of Western civilization. But the human situation is more diverse — and more mysterious — than Cultch estimated, and reflection upon the situation requires depth of study more than breadth of familiarity. Cultch as prologue rather than capstone seems an appropriate epitaph. — Carl Benton Straub, Professor of Religion and Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies

Campus Secrets

With friends Sally Williams ’74 and Peg Kern ’74, I came to know many odd places on the Bates campus. We prowled through the abandoned dining hall in Rand, the dingy locker room in its basement, and the dark corners of the lower floor of the “old” Chase Hall. In fact, we might have been the last students to bowl a game on the warped duckpin alley down there. But perhaps the strangest place of all was the upper reaches of the Chapel. One evening, we discovered a trap door in the ceiling of the room in the front right-hand corner of the building. Of course, we climbed up into it, and found ourselves standing in the middle of the pipes to the organ. None of us had ever seen organ pipes up close before, and we were fascinated. The ones we found were wooden boxes, anywhere from 1/2 to 4 inches on a side. Some towered over us, others were inches high. We were so engrossed in examining them that we didn’t hear Marian Anderson enter the Chapel until he started up the organ and everything around us started to wheeze and heave. The three of us were paralyzed for a minute or so, and then realized that we had to get out of there before he deafened us. We let ourselves back down to the main floor and scooted out the side door. I don’t know what Professor Anderson thought was going on. We never had the courage to ask him. — Christine Terp Madsen ’73, former Class Notes editor

Segregation Solver

To say that Bates changed while I was there is to make a molehill out of a mountain. During my first year, we had a house mother in Page — a woman in her late 50s whose job was to make sure our virtue stayed intact: no men allowed on the dorm floors at any time, curfews, and sign-in/sign-out sheets. Even the maintenance workers had to ring special bells before venturing near our rooms. By my senior year, there were coed dorms and not a house mother in sight. The transition wasn’t easy. As juniors, my friend Deb Hibbard ’73 and I were the proctors (residence assistants) in Rand Hall, home to 47 first-year students and a smattering of others. The first three floors were open on a limited basis to men, but the top floor was closed to them. By then, no other residence floor had this restriction, and Page, the site of my first-year sequestration, had been turned into an “experimental” coed dorm — men and women on separate floors. So the 20 or so women stuck on the top floor of Rand quickly realized that they were considered peculiar, since they lived in the only place where men dared not show their faces, and they resented the restrictions. Deb and I did a quick survey and found that only six of the women had made no-men-allowed their first residence choice; everyone else had grudgingly given it as second choice, no doubt to mollify their parents. Armed with this information, we approached Dean of Women Judith Isaacson ’65. “Dean Judy” had already swept out many quaint customs — white gloves and hats for tea with the dean, for instance. She was even radical enough to give women keys to their own rooms! I like to think that it was with a sense of sly delight that she agreed to open this last bastion of chastity to the rampaging hormones of Bates men. — Christine Terp Madsen ’73, former Class Notes editor

Two Guys, a Couch, and Amazement

Sitting down on a couch with Stephen Spender, visiting lecturer, to talk about his poet pals of the 20th century. Me, him, couch. Could this be happening? — Peter Moore, Executive Editor, Men’s Health Magazine

Gwendolyn Brooks’ Groceries

A fledgling book buyer in the Bates College Store, I was privileged to meet the subject of my Bates thesis just a few years after graduation. Poet Gwendolyn Brooks was reading her poetry in Chase Lounge, and I was to take her back to her hotel room after the reading. Nervously, I waited while she signed books and spoke with audience members. She had two requests of me: a quick book browse and a few groceries so she could eat while she wrote at her hotel. Where to take her but the Bates College Store, where she pronounced the poetry section “wonderful.” Then, it was on to the Shop and Save store on Sabattus Street, where she stocked up on salad, and then to the Ramada. This very white Maine girl finally found her voice and asked the renowned black poet from Chicago how she managed to discipline herself to write. “Why, girl, I write in my slippers and my bathrobe every day before anyone else is awake.” — Sarah Emerson Potter ’77, Director of the Bates College Store

Scale Models and Screeching Metal

For a Boston Bates Club meeting in 1980, I was charged with delivering speakers (a few students and physics professor George Ruff among them) and a scale model of the new indoor pool and athletic facility to the Museum of Science in Boston. We loaded the scale model into the plywood javeline box, fixed it atop the 15-passenger van, and set out. We made it through the infamous Boston traffic and reached the museum’s parking garage, which had clearance for the van — but not for the javeline box. There was an alarming screech of metal tearing off metal as the javeline box, Tarbell Pool, weight rooms, track, and tennis courts all stayed on the garage’s first level and we proceeded to the second! The model survived but its scale model Bates people — and the van driver — were in serious disarray.

—Sarah Emerson Potter ’77, Director of the Bates College Store

Acid Rain…in Maine?

As was my custom, toward the end of my interview with the prospective student (from Arizona) I asked if he had questions for me. He asked me what we did on campus when it rained. I looked blank, so he added, “Do you have protective gear, so you won’t get burned?” I said “burned by the rain?” He nodded. “Yes, by the acid rain – doesn’t it damage your skin?” — Virginia Harrison ’63, former associate director of admissions

The Campus Taj Mahal

When Bud Bechtel’s house was being renovated, before officially becoming Lindholm House, Norm Ross would pace the sidewalk along Campus Ave., sometimes with his construction helmet on. He called the building “the Taj Mahal” and grumbled about the high price tag. He told me there was no need for such a grand place for something as mundane as college admissions. — Virginia Harrison ’63, former associate director of admissions

Someone From Home

One fall I was at a big college fair in Denver. Thousands of people were there, to see hundreds of colleges. My BATES sign was posted high on the wall behind me. Along came an elderly man, who stopped at my table and peered at me, then down at the colorful campus pictures on the viewbooks. He asked if I was really from Lewiston and when I smiled and said yes, tears filled his eyes. He told me he had been a Lewiston firefighter and one of the fires he remembered most was the big Parker Hall fire. He was one of the men high up by the top floor, where the fire was so intense. We found some shots of Parker in the display books I had — he couldn’t get over the fact that someone from “home” was talking with him in Denver. His lungs were badly damaged from so many years as a firefighter, so his doctor had advised him to move out west where the air was cleaner. — Virginia Harrison ’63, former associate director of admissions

Picketing Parents

I remember the year when I realized that Bates had truly arrived among the colleges in the very selective and highly desirable category. It happened suddenly, and at the time was not pleasant. It was March, and the admissions deans were in committee. We met for long days in the conference room, going through the decisions one by one. That year we could admit only 25 percent of the applicants, so our discussions were intense. Each one of us had to struggle to stay objective even as applicants we knew well sometimes were voted down. Across the hall on the other side of the heavy closed door of our meeting room, a large group session for visiting families was going on in the lounge. Normally visitors in March are juniors in high school with their families, but that day was different. We decided to break for lunch, for we were all drained from the morning’s work. As we opened the door, we were startled to find a small crowd of parents standing there waiting for us. It was like being met by the clamoring press — lobbying began right there in the doorway, in front of the water cooler. These families really wanted Bates and had to make sure we knew it. The incident lasted only a few minutes, but it was a milestone moment for me. — Virginia Harrison ’63, former associate director of admissions

The First Shorts

Bates’ first Short Term, my freshman year in 1965-66, was open only to our class, so it was a very small group and a friendly, informal way to learn (even though the term was eight weeks long and we took nearly a full course load). Students won the “right” to wear Bermuda shorts to class, perhaps the first break in Bates’ dress code. We all had T-shirts that said “Camp Batesie” with an illustration of President Phillips’ face. We showed movies outdoors on a sheet hung from the back of Schaefer Theatre. Short Term offered the opportunity to graduate in three years, a goal I later gave up when I decided to go JYA, but I was glad for the option.

-Pam Baker ’69, professor of biology

Making the Grade

The class was comparative literature and the professor was Werner Deiman — my favorite. I loved to listen to him talk as he slouched against his desk, flipping the end of his tie with his left hand. My notes were always detailed, not only with material relevant to the topic at hand, but also with the fascinating asides he added. But I had never earned an A from him. And so when it came time for him to return our research papers, I didn’t have much hope. I didn’t even look at his grade or comments until I was in the hallway outside Pettigrew 218. “Thank you for this paper,” he wrote. “I learned a lot from it.” And he gave me an A. I shrieked and turned to my friend, Julia Holmes ’74. She flipped to the end of her paper and shrieked, too. We grabbed each other and jumped up and down.

Christine Terp Madsen ’73, former Class Notes editor

Into the World

Short Term, my junior year. I was taking a course in pre-war British lit — E.M. Forster and the like — which meant we were reading a lot about the formation of our modern world, but from a pre-fall perspective, before the impending cataclysms. Heady stuff when you’re 20, which is no doubt why we’d leave Ann Lee’s classroom in the mid-afternoon and head for the Blue Goose. After one such session, I stumbled up Wood Street in a heightened state of literary stimulation and boozy melancholy, and encountered a schoolyard full of children. One boy was being taunted by cruel classmates, and I crashed hard into similar scenes from my own childhood, plus a whole W.B. Yeats “Among School Children” hangover. I ripped myself away from that scene, lamenting for the poor picked-on kid, and continued back toward campus — an emotional refugee. But my psycho tour wasn’t complete, because as I weaved up the sidewalk a half block away, my eye was drawn by a huge orange cat crouching next to a hedge. I stopped, his green eyes looking into my blue ones. Shudder. Then he turned his head and in one swift motion plunged through a gap in a bush and landed claws-first on a pigeon who’d been innocently pecking away on the other side of the hedge. The cat tore into the bird’s breast with his teeth, opening a gruesome red tear. Here was Cruelty, Part 2: The Natural World, and I felt it keenly, overwhelmingly, and OK, drunkenly. But what strikes me about it all, in retrospect, is how alive I was back then to every sensation, every idea, every person, every emotion. Bates caught me at a time in my life when I was just discovering how much joy and pain were possible.

Peter Moore ’78, executive editor, Men’s Health

Fit to Be Tied

In 1961, Bates football tied UMaine. Coach Bob Hatch used an innovative spread formation on offence, and it befuddled them. Despite the 15-15 tie, everyone knew it was a Bates victory against one of Maine’s best all-time teams — they were the undefeated Yankee Conference champs. After the game, in the most genuine display of school spirit I ever witnessed, students lined both sides of the walk from Alumni Gym to the Den, waited for the players to emerge from the locker room, and cheered each player as we walked to the Den.

Web Harrison ’63, head football coach, 1978–1991

On the Beach

College is a place from which to view the rest of the world and to re-view one’s self in light of the world’s measurements. The re-view occurs through experiencing the juxtapositions between “truths” taught and learned, and the enveloping society’s expectations for each generation to join in, join up. A revelatory moment of these collegiate tasks was the moral struggle of members of the Class of 1968 over whether to act in conscientious objection to the Vietnam War. I remember a cold winter walk along Popham Beach with a senior in such a struggle. All around us was the growing tumult of the politics of Vietnam and of the principalities of the counterculture. There on the beach was a moment of time and a modicum of space to wrestle with citizenship, sonship, friendship, loves, and fears. He came to act as he saw fit. I have known countless other students to act in other times, with both conscience and a teacher their steady companions.

Carl Benton Straub, professor of religion and Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies