Your Page

While undergrads and prospective students are drooling over the promise of a new $28.65 million dining Commons and cross-campus walkway (Bates Magazine, Winter 2006), some of us old grads have been reminiscing about wartime dining at Bates in 1943 and 1944.

While undergrads and prospective students are drooling over the promise of a new $28.65 million dining Commons and cross-campus walkway (Bates Magazine, Winter 2006), some of us old grads have been reminiscing about wartime dining at Bates in 1943 and 1944.

When the Navy’s V-12 unit arrived on campus on July 1, 1943, the campus became the sea, and the sailors took over Parker Hall and “New Dorm,” now Smith Hall, as their “ships.” In the process, the Navy evicted civilian men from the dining hall in John Bertram Hall.

Where would these few civilian men eat? At the time, women dined in Fiske Dining Room in Rand Hall, but campus rules did not allow men to eat with women, except as invited guests on Sundays. And anyway, the extreme wartime decline in male enrollment — from about 400 prewar to about 50 — was not met with any decrease on the female side, which actually ticked upward. So Fiske was full.

In a pinch, the College turned to Bernadette Vaillancourt, who ran a boarding home at 193 Holland St., about a block from the Quality Market, and starting in 1943, I and many of my fellow on-campus civilian men got their three squares from Mrs. Vaillancourt.

- Submission guidelines for Your Page essays are posted here.

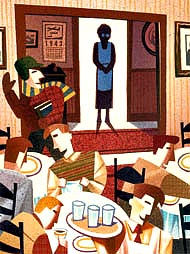

By then, the fall term was starting in late October due to the accelerated, year-round wartime calendar that included a full summer term. During freshman orientation, we gathered in front of Roger Bill and were escorted by an upperclassman down Wood Street to its intersection with Holland, where we were ushered into a warm, homey establishment with tables, in several first-floor rooms, covered with white tablecloths, fine utensils, and china. The aroma of the meal being prepared enhanced our already ravenous teenage appetites, while the comfortable and relaxed setting was in stark contrast to the more institutional dining hall a few blocks north.

Over the next few weeks, this ambiance contributed to the growth of a genteel, relaxed, and conversational mealtime rather than a rush to eat and get out the door. Over the longer term, faculty members would drop by for a meal to continue dialogues begun in class and offices. The topics were not only academic but also covered current world events. John Margarones ’48, who was commuting to campus in his final term, continued to take lunches at “Mrs. V’s” with Robert Covell, a young instructor in history, and remembers the food as “infinitely superior to the menu at Commons.”

Ken Munroe ’47 simply states that dining at Vaillancourt’s was “one of my fondest memories.”

Mrs. Leo Vaillancourt ran her boarding house for 23 years, from 1927 until she moved to Old Orchard in 1950. She died in 1993 at age 94. She is remembered as very genteel, thin, myopic, and energetic. Some of the students conversed with her in French, although she also spoke English. Her son, Gerald, was the server.

Henry Inouye ’47, who came to Bates from a wartime internment camp for Japanese Americans, was assigned by the College to be kitchen helper for Mrs. V. As a teen, Henry had learned in camp to be a chef, and he let us know a few of Mrs. V’s kitchen secrets, most having to do with the standard boiled meat and potatoes menu. For one, Maine potatoes should not be mashed, lest they become glue-like. And to disguise the lean and stringy wartime horsemeat, Mrs. V dowsed it with tomato paste and cheap red wine. While alcohol was not on Mrs. V’s menu, Henry recalls the Harry Rowe admonition to display no beer bottles in the front windows of Roger Bill.

Several of our number, including Henry and Brenton Dodge ’48, were later sent into kitchen duties at Rand Hall, where the summer fare was cold macaroni and cheese salad and the culinary high spot was Saturday beans and hotdogs!

Complementing the warm memories of Mrs. V’s, there are memories of the long, cold walks down Wood Street to get to our meals. Since we began in late October, it was dark for the trek to breakfast and dark again after supper. Some of us still recall the sound of the Hathorn bell reverberating off Wood Street homes, calling us to classes from our Franco-American meals.

Still, amidst the memories there are unsolved mysteries. I and others believe we were required to turn our ration books over to the College, but we’re not sure how, exactly, Bates compensated Mrs. V for her service to Bates and its men. As the new Commons takes shape, we’ll try to round out this small portion of Bates history and, perhaps, honor it with a niche in the new building. Tomorrow’s students should know about this chapter of friendship and fellowship around the dinner table.

Stanley Freeman ’47 and his wife, Madeleine Richard Freeman ’47, live in Orono. He thanks his fellow contributors and the staff of Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library.