By George

In the late 1970s, when then-Dean of the Faculty Carl Benton Straub met with the science faculty to discuss plans for a new building, George Ruff told Straub that the sciences didn’t need a building. What they needed was equipment to put in a building.

Ruff’s colleagues agreed, and further said that the humanities had a greater need for a new building. In the end, the sciences got better equipment, and the humanities got Olin Arts Center.

Charles A. Dana Professor of Physics George Ruff peers through an optical pumping apparatus in Carnegie Science. Ruff built the exterior coils as a graduate student, and the rest was built at Bates by Ruff’s students who, over the years, used the equipment during their thesis work. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

Even so, the department budget back then couldn’t easily fund the purchase of all the equipment that George, an expert in atomic and laser physics, wanted for the hands-on research he did with students, for his electronics Short Term, and for the introductory and advanced physics labs, also hands-on in nature. So he began visiting various companies, heading out in his VW bus, to see if they would donate equipment to Bates.

Bell Labs was then one of the premier physics laboratories worldwide, and they routinely replaced good equipment with the next generation of cutting-edge apparatus. George convinced them to donate some of their cast-offs to Bates — equipment that in fact was better than what many research universities had — and a lot of this stuff came to Bates in U-Haul trucks that George drove.

This essay is based on a talk given by Professor of Physics Mark Semon at a celebration dinner for the College’s Dana Professors. Ruff is one of six who hold this great Bates distinction.

Not only did George acquire equipment, he also built it. When he wanted lasers he blew the glass tubes himself, built his own equipment for evacuating them, and built his own system for putting the right mixture of gases in them. He’s still doing it. When he wanted more diode lasers and higher-quality mirrors and beam splitters, he bought discarded videodisc players and had a party where he and his electronics students took them apart and extracted the requisite lasers and optics.

When George arrived at Bates in 1968, he had new ideas for how to execute some traditional experiments. This required equipment that wasn’t available commercially, so Ruff built a machine shop in the basement of Carnegie. While the tangible result was better equipment for less cost, that machine shop has also played an unlikely role in the reputation and culture of the Bates physics department.

For example, during a visit to Trinity College in Hartford for a physics colloquium, my colleagues and I discussed experiments that our students did in introductory courses. I said we did the Millikan oil-drop experiment, the Franck-Hertz experiment, and the Michelson-Morley experiment, among others. My peers reported that their students also did those experiments — adding that they never really worked, of course. A hush fell over the room when I said that ours did work. How, they asked, could those experiments possibly work with the typical equipment available for an introductory lab? Now you know the answer.

Every student in George’s laboratory physics course was required to do a project in the machine shop on the milling machine. This created a lot more work for him — arranging projects and supervising students to make sure they didn’t cut off a finger.

George did it anyway because he thought it important for his students to have this experience. When Heather Inglefield McCulloh ’89 began her Ph.D. program at MIT, she was the one of the few in her graduate program with machining experience. “That experience, plus being more than willing to do my own machine work, certainly got me some degree of respect. And it was incredibly useful,” she said. Ph.D. in hand, she’s now an engineering manager with National Semiconductor.

Several years ago, when George was on a sabbatical, the well-known experimentalist and author Robert Hilborn visited Bates as the outside examiner on the honors panel of one of our majors. I showed Hilborn around Carnegie, and since I’m a theoretician and not an experimentalist, this could have been a disaster since I might have pointed to various equipment and said, “Well, there’s this, and then there’s that….” But our tour became a great success when we walked into George’s lab, where one of his experimental setups captivated our visitor, who spent a good part of the afternoon making drawings and notations to take back to his own lab.

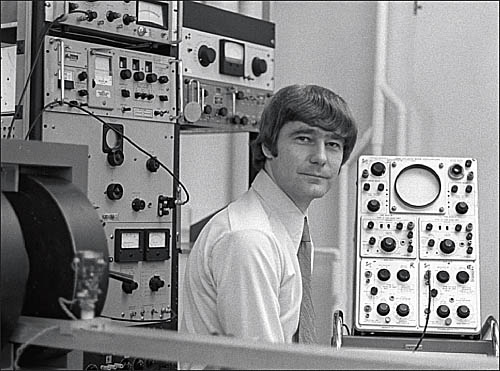

Ruff, surrounded by the tools of his trade, in his Carnegie Science Lab in 1977.

All of George’s skill, ability, and knowledge have one central aim: to give Bates students the very best education he can — not only in physics, but also in the liberal arts. George believes some of the best teaching goes on outside the classroom, and I remember vividly the December photograph from an old Bates wall calendar, showing Carnegie at night, framed by snowdrifts, its lights blazing in the deep winter darkness. Looking closely, one could see that the shining lights were in George’s labs and offices. It wasn’t unusual for his thesis students, during holiday breaks, to move in with the Ruffs on Walker Avenue so they could continue to work on their experiments.

And those thesis students have gone on to pursue a wide variety of careers at a wide variety of places. When Nobel Prize winner William Phillips began his talk at Bates in 2003, he said how glad he was to finally see Bates, since so many Bates grads kept showing up in his labs.

When the sciences ultimately did get new space with the 1990 addition to Carnegie, George was a key member of the planning committee, spending hours poring over blueprints that covered long lab benches and giving practical-minded input on the best locations for outlets, windows, benches, and even some walls. If you were to study the plans for the basement, you might notice a heating duct that starts in one room and ends in another without ever entering or leaving the HVAC system. It goes nowhere. But if you went looking for it while visiting campus, you’d likely find physics students using that duct to make accurate measurements of the speed of light. George had redesigned the experiment so he could do it in a heating duct, rather than taking valuable building space.

With his talent, George could have gone almost anywhere, and he was once offered a job overseeing graduate labs at a major research university. When asked why he didn’t take the position, he said he preferred to work with Bates students. That said, Ruff has worked with top research groups during his sabbaticals — at Stanford Research Institute (now SRI), MIT, Arizona, Connecticut, and Virginia, as well as Germany, New Zealand, and Austria abroad.

I was sitting in a friend’s lab at the University of Colorado one summer day in 1976, just before I came to Bates. Waiting for my friend to finish his work, I picked up the latest issue of the Physical Review Letters, the premier journal in our field. The words “Bates College” caught my eye among the credits for one paper. One of the authors was George Ruff, and among the co-authors was Nobel laureate Willis Lamb. Their paper, “Observation of the Infrared Spectrum of the Hydrogen Molecular Ion HD+” reported a successful, high-precision measurement that added key knowledge to the emerging field of astrochemistry, which uses spectroscopy to study the chemical elements found in outer space.

A colleague said that George’s absolutely independent point of view, in science and in life, is rooted in the concept of “wonder.” It infuses his interest in science, teaching, lab work, and people, and it has had a wondrous effect on our department.

In January 2002, three physics researchers visited Bates as part of a national project trying to determine why some undergraduate physics programs attracted more majors and, specifically, more women than others. Then and now, Bates represents something of a model on both counts. We have consistently been among the top 10 undergraduate institutions in the country in terms of the number of physics majors. In addition, Bates has consistently had a higher number of female majors than at least half of all the other colleges or universities in the country.

During their two-day stay, the visitors conducted a focus-group interview with the physics faculty, and the lead investigator asked the first question: What were we doing to attract so many majors, and so many women? Most of us were at a loss for words; we never really had “done” anything. We sat in silence until George finally said, “Well, we treat our students like human beings. We work with them, we listen to them, we enjoy them, we care about them.”

And when they published their findings in a leading journal, this ethos was an essential element of their discoveries.