Wake Up Call

Professor of German Denis Sweet’s new course, “Wake Up!” educates Bates students one experience at a time

Story by Denis Sweet — photographs by Phyllis Graber Jensen

It was Short Term 2008, the debut of my course, “Wake Up!” The rain was pouring down in the woods of southwestern Massachusetts, pattering hard on the blue tarp that I was crouched under.

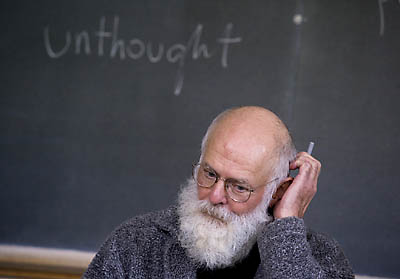

In a Bates classroom, author Denis Sweet, professor of German, is lost in “unthought.”

It had been pouring rain like this all day. And it was cold. I hadn’t eaten, or rather, I had deliberately not eaten. I was fasting from dawn to dawn. I had put on all my clothes, including the rain gear, and had crawled into the sleeping bag to try to fend off the cold (but not to sleep; the point was to keep watch through the night and greet the first light of dawn). But every hour or so, I would struggle out of the sleeping bag and methodically peel off all the layers of clothing. I had visitors, you see, and needed to begin another hunt for fat, colorful dog ticks. After 13 I stopped counting.

What, for goodness’ sake, was going on here?

- View a multimedia story about Denis Sweet’s course produced by Phyllis Graber Jensen

For me and the 12 Bates students scattered about in the woods who had signed up for the course, the 24-hour solo fast in the Berkshires was the intentional part. Everything else was a freebie from the unknown. And the most curious thing of all, when it was all over, I felt a genuine gratitude for all of the experience, including the cold, rain, and ticks. They had taught me something unexpected and invaluable. I’ll come back to this.

A chain of such experiential moments — the solo fast being just one of the more salient examples — stretched from one end of Short Term to the other. As far as I knew, nothing quite like “Wake Up!” had ever been tried at Bates before. It was a hybrid that wedded rigorous academic inquiry with direct, personal, unmediated experiential learning. Each of the halves reinforced the other.

In a symbolic ritual, Alice Thompson ’10 of Pittsburgh, Pa., has her face washed by Kate FitzGerald ’10 of Chilmark, Mass., at Bradbury Mountain State Park.

I find that we live in an intensely cerebral culture. One Buddhist thinker, when asked what the problem was for Westerners, responded simply, “Lost in thought, lost in thought.” Rather than living in the moment and paying close attention to phenomena as they occur, we often recycle habitual narratives. The stories in our heads become the “reality” we inhabit. We become lost in thought. Our day-to-day lives are characterized by what I call automatisms: deeply ingrained habits of mind that act as perceptual filters and subconscious pigeon-holers.

Buddhism calls it sleeping or sleep-walking. Waking up (hence the course title) requires a lot of attention, mindfulness, and determination, through age-old practices like daily yoga and Vipassana (insight) meditation to the solo fast.

In Vipassana, one learns to quiet the mind. In the beginning, a 20-minute session in our classroom on the second floor of Dana Chemistry was an ordeal. Thoughts, memories, desires, anticipations, worries, preoccupations jumped helter-skelter through the students’ minds (Buddhists call it “monkey mind”). Five weeks later, after a lot of practice, these same students commented that our last 20-minute sit together seemed more like five. They had grown far more centered and mindful.

| So, is this what should I be doing as a Bates professor? Is this what I should be offering my students? |

We spent a week at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies engaged in a study retreat. Silence during certain hours of the day was combined with several hours of sitting and walking meditation followed by a three-hour seminar run by the Barre staff. Soon, a momentum was at work in the course, spanning the practices of furthering self-awareness, tying them into critical reflections on our relationship to nature, culminating in greater social commitment and heightened awareness of and interaction with others in the larger society.

A quarter-century of teaching at Bates has shown me how adept Bates students are at articulating abstract notions in academic papers. But at the same time they remain teenagers seeking their way in life. Often, I find, there is a profound disconnect between the two. So I wanted to provide a venue for learning and for experiencing some things that are essential to the development of young people, yet which they are otherwise not getting in academic courses.

Here’s an example. Two by two, students went into the woods to slowly, mindfully, wash the face of their partner by dipping a washcloth in the water of the little brook running there, and symbolically washing off the social kinds of masks we employ vis-à-vis each other. The ritual was a way of breaking through habit and comfort, and coming to realize that all of us bear these masks, whether we’re aware of it or not. A kind of gentleness and tenderness and awareness of oneself and the person right in front of you came to the fore.

So, is this what should I be doing as a Bates professor? Is this what I should be offering my students? The German philosopher Martin Heidegger talks about creating a situation where learning can take place. My task then, at least as I see it, is to create a situation where intense learning can take place in individuals. But this learning should also contribute to the needs of the larger democratic society, which surely requires an awake, critically aware, and engaged citizenry.

And those dog ticks I mentioned? They taught me humility, patience, limits, and the wonderful humor of the situation. A citizen needs those too.