Historically Black

Spelman and Morehouse colleges offer something that Bates can’t — and that’s just the point

Lisa D’Oyen ’09 of Kingston, Jamaica, holds her cell phone in one hand and two open boxes of Hostess crème-filled chocolate Zingers in the other. Standing beside a table lined with edible snacks, lubricated latex condoms, and fact cards, D’Oyen and her psychology classmates share information about HIV/AIDS with students heading to lunch. Their sound system broadcasts hip-hop as a Yale Divinity School recruiter also vies for student attention.

A standard Chase Hall tableau? Not today. This afternoon, D’Oyen stakes her ground in Manley College Center at Spelman College, the historically black women’s college in Atlanta, where she and Mbali Ndlovu ’09 of New York City are spending their fall semester.

Like any of the College’s myriad off-campus study offerings, the exchange program with Spelman and Morehouse hopes to offer students the right experience at the right time: during their junior year, when students are equipped to dig deeper into their intellectual, social, and emotional beings.

As part of her pschology course, Lisa D’Oyen works at an HIV/AIDS awareness table in the college center at Spelman College, the historically black women’s college in Atlanta.

For D’Oyen and Ndlovu, part of this exploration will involve race, for at Spelman and Morehouse, the nation’s two premier historically black liberal arts colleges, “the courses and the context provide a sensitivity and awareness of racial issues that,” says Steve Sawyer, associate dean of students and director of off-campus study, “is impossible to replicate on a small New England campus — no matter how well-intentioned.”

Another overlay is gender. Spelman wants visiting students like D’Oyen and Ndlovu to leave the school with a “stronger sense of self, their place in the world, and what the Spelman ‘sisterhood’ is all about,” says Desiree Pedescleaux, who oversees the institution’s domestic exchange programs.

Ndlovu and D’Oyen get a sense of the sisterhood from “The Black Female Body in American Culture,” taught by M. Bahati Kuumba, associate professor of women’s studies. The professor discusses how the human body is a system of symbols and how, for black women in U.S. society, those symbols can suggest a political struggle.

After class, Ndlovu schedules an appointment with Kuumba, wanting the professor’s advice on designing a senior thesis topic for her Bates majors in African American and women and gender studies.

Everything about the professor resonates with the two young women. “She’s an activist. She’s been out there. And she’s very political,” D’Oyen says. True, there are political activists on the Bates faculty, she says, but at Spelman “we get the black perspective from black women. We can relate.”

“Like for the first time in my college career,” Ndlovu adds.

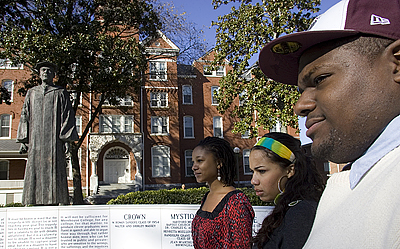

Mbali Ndlovu ’09 (left) and Lisa D’Oyen ’09, who studied at Spelman College during the fall, join Claudeny Obas ’09, who spent spring 2006 at Morehouse College, at the Benjamin E. Mays National Memorial at Morehouse. Mays graduated from Bates in 1920.

One morning in late November, D’Oyen and Ndlovu head across the street to Morehouse to see the Benjamin E. Mays National Memorial. At once, the Bates-Morehouse connection seems real, though they’d heard about it all fall. “Every Morehouse student we met automatically knew what Bates was,” Ndlovu says.

At the monument, the women are joined by Claudeny Obas ’09 of New York City, who’s in Atlanta visiting friends he made while studying at Morehouse in 2006.

Obas, a veteran of mostly white educational environments, talks about what might be gained from a semester at Morehouse, particularly by someone who’s never been in a minority situation — racial, sexual, religious, or other: “an understanding of what it’s like not having as many people to lean on in terms of your peers, and [having to go] outside of your comfort zone just to make the effort to reach people.”

For Obas, the semester started with getting “stuck in a room for two hours learning the school song,” he recalls, but the indoctrination into the Morehouse mystique paid off. “I felt I was joining a long line of prestige,” he says. Obas’ semester at Morehouse deepened his understanding that he “works better” in the multifaceted social milieu of an urban college. “I’ve always known that, but it was made much more apparent to me at Morehouse.”

He experienced one particularly glittering facet of Morehouse life thanks to Roland Davis ’92, assistant dean of students at Bates.

| Bates, Morehouse, Spelman

The connection between Bates and the nation’s two premier historically black liberal arts colleges — Morehouse for men and Spelman for women — dates to 1940, the year Benjamin E. Mays ’20 began his 27-year Morehouse presidency. The Bates-Morehouse-Spelman Exchange Program was established in 1994, the centennial year of Mays’ birth. While the program has had modest student participation from both sides over the years, Bates is now focusing greater attention on this and similar initiatives, part of redoubled efforts to incorporate a wider spectrum of people, perspectives, and disciplines within the Bates experience. |

Davis, whose father chairs the Morehouse board of trustees, said that if Obas was accepted for the Morehouse semester, Davis would get him tickets to the school’s “Candle in the Dark” gala.

And that February, Obas was indeed in black tie at the Hyatt Regency Atlanta to see famed photographer Gordon Parks and Tony Award–winner Geoffrey Holder receive their Candle awards for excellence in their fields. Obas also witnessed several Morehouse alums receive their “Bennie” awards for service, achievement, and trailblazing.

“It was quite the experience,” Obas says.