My City Was Gone

Chinese artist Wang Jing looked to the past to try to make sense of a baffling present.

For years she watched many fine old buildings in Shanghai, where she lives, and in other Chinese cities being razed in a blitzkrieg of new development.

Mark Bessire, director of the Bates College Museum of Art, is shown with an image by Xing Danwen during the installation of the exhibition Stairway to Heaven.Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

“I felt very sad, and hoped to do something to deliver myself of that,” she says. So Wang began making sculptures of the new buildings from snap-together construction sets by the Chinese toy company Blocko. She had played with such toys as a child.

Like a child’s Blocko creations, contemporary Chinese buildings are often colorful and grandiose but conceptually vacant. “Most of them just are things without design. Some of them are very ugly,” Wang says. And like the toys, they go up fast.

As skyscrapers and shopping malls have supplanted old and close-knit neighborhoods, Wang is one of many Chinese artists exploring the urban impacts, emotional and visual, of China’s warp-speed economic makeover. She is one of 17 artists showing their responses in Stairway to Heaven: From Chinese Streets to Monuments and Skyscrapers, the year’s major exhibition at the Bates College Museum of Art.

It’s an ironic truth that the same conditions that give these artists so much thematic raw material are, simultaneously, making it ever easier for them to work as artists.

Emphasizing photography, the exhibition portrays the city through three wide lenses: the changing forms and meanings of public monuments; the forests of skyscrapers springing up like bamboo; and the street-level scenes that are disappearing as those skyscrapers hoist residential living into the heavens.

Museum director Mark Bessire assembled the show along with his frequent curatorial partner, Raechell Smith, who directs the H&R Block Artspace at the Kansas City Art Institute. The exhibition, which travels to K.C. after Bates, is timely in more ways than one. (A book published by University Press of New England will accompany the exhibition.)

The obvious hook is the Summer Olympics in Beijing. The quadrennial strive-fest holds potent national symbolism for a China competing for a place on the world’s political and economic medal stand. As such, the Olympics provide a sharply contrasting context for the artists’ wry, probing, and often despairing views of the new upwardly mobile China. (The exhibition title is not a shout-out to Led Zeppelin, but instead an ironic play on such ideas as soaring skyscrapers, soaring national ambition, and China’s traditional self-image as “Heaven on Earth.”)

T

“On the Wall, Haikou 6” is a 2003 C-print by photographer Weng Feng.

What may be their biggest stimulant, especially in view of decades of Maoist repression and manipulation of artists, is the government’s newfound tolerance of free — well, fairly free — expression. It’s riveting, says Bessire, “to watch China move from having practically no artists, except for under government control, to this sudden incredible creativity that was stifled for 50 years.”

And with money pouring into the country, art patrons are spending more and the arts infrastructure is growing apace, says Beijing photographer Luo Yongjin. “There are more and more galleries, art museums, and art events.”

Such as the Shanghai Biennale that drew Bessire to China in 2004 and 2006, as he sought material for a Bates museum show to coincide with the Olympics. Viewing thousands of artworks during hundreds of studio visits, he found the skyscraper motif pervasive.

“Forever, in Chinese cities, there was horizontal landscape of low buildings, street-level life. Now all those neighborhoods are being demolished and the skyscrapers re going in.”

Photographer Xing Danwen’s response to the resulting sense of dislocation was the Urban Fiction series of digitally altered color prints depicting a sterile world of cookie-cutter apartment towers. Yang Yongliang, meanwhile, used Photoshop to mass skyscrapers and construction cranes into the traditional format of ink painting on scrolls.

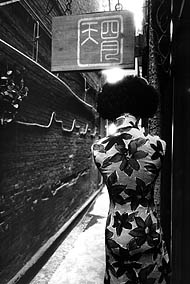

Striving to illustrate a vanishing flavor of street life are photographers like Gu Zheng (who curated the 2004 Bates exhibition Documenting China, now on a national tour). Gu’s grainy black-and-whites capture edgy sidewalk encounters and jarring intrusions of Westernized consumer culture.

Finally, there are disparate approaches to the theme of monuments, a theme especially fraught in a land whose 5,000-year culture has undergone such disruption in just three decades of economic reform.

“What is an artist going to do with a monument that is pre-Mao, like the Forbidden City or the Great Wall, when the new icons are the skyscraper and the bullet train from the Shanghai airport?” Bessire muses.

Photographer Ai Weiwei took an international view of the monument issue with a series of one-fingered salutes to such icons as the White House, the Eiffel Tower, and Tiananmen Square.

Broadly defining “monument,” Luo Yongjin is showing blunt, distant black and whites of bombastic new government edifices in one series, and in another, wildly quirky highway gas stations that are being replaced by uniform international designs.

As for Wang Jing, her contribution is “The Biggest Chinese Food in 2008.” It’s a Blocko version of a building that she actually likes, the National Stadium built for, and a popular symbol of, the Beijing Olympics.

The sculpture caricatures the stadium’s cakelike look. But the confectionery resemblance is more than physical. “So many people hope to get a piece of the ‘big cake,’” says Wang. “Government leaders, the businessmen, the athlete, artists like me, and so on.”

She adds, “My art works are always not very heavy. If American viewers could smile or laugh when they see my work, it is enough.”