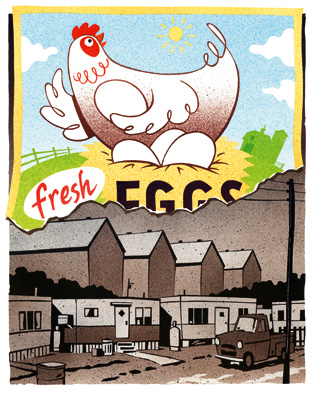

Good Eggs

The national egg-salmonella scare didn’t surprise these social-justice Batesies

By Edgar Allen Beem

Over the summer, a salmonella outbreak that sickened more than 1,600 people nationwide was traced to an unsanitary factory farm in Iowa, prompting the recall of some 550 million eggs.

One of the farms involved in the massive recall, Wright County Egg, is owned by Austin “Jack” DeCoster, an industrial farmer whom the Iowa Supreme Court in 2002 labeled a “habitual offender” against state environmental laws.

Here in Maine, headlines involving Jack DeCoster and eggs are nothing new.

Over the years, DeCoster’s mega-egg farm in Turner, about 14 miles from campus, has been investigated for myriad problems, from child-labor and immigration violations to the illegal dumping of chicken carcasses. (Now known as Quality Egg of New England, the operation was not involved in the 2010 national egg recall.)

Mostly, however, the farm has drawn fire for its poor treatment of migrant farmers, who live on farm property in what some have described as ramshackle, Grapes of Wrath housing. Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, LL.D. ’01 once said that the DeCoster farm in Turner was “an agricultural sweatshop.”

“It gives students a sense of what it’s like to do social-justice work that really is worker-centered — it’s not about themselves.”

By virtue of this multifaceted ignominy, the farm and its largely migrant work force have long been a real-world, hands-on classroom for Bates students, professors, and alumni, who have helped address a host of human rights, health and safety, labor, and environmental issues at the DeCoster facility.

“The best thing about it,” Professor of English Carole Anne Taylor says, “is that it gives students a sense of what it’s like to do social-justice work that really is worker-centered — it’s not about themselves. It’s not charity work.”

From 1998 until 2003, Taylor was an adviser to the Maine Rural Workers Coalition, whose goal was to help rural workers develop leadership skills. Along the way, the group got help from Bates students as translators and English tutors.

Mike Travers ’00 helped organize the MRWC and served on its board of directors, otherwise made up mostly of migrant workers. A double major in American cultural studies and Spanish, Travers was an invaluable translator, yet he exhibits a healthy perspective about his contributions.

“I didn’t know the answers,” says Travers, a bilingual coordinator at a Los Angeles elementary school. “All I could do for them was translate what they wanted translated.”

In 1999, when DeCoster workers won a settlement in a class-action lawsuit to recover unpaid overtime, Bates students and faculty were on the front lines, doing legwork and phone calling for the workers’ attorney, Donald Fontaine.

Taylor and others worked the phones to track down 1,275 former DeCoster workers in Maine, Texas, and Mexico who ultimately received a reported $5 million in overtime. A typical class-action lawsuit, Fontaine explains, locates about 5 to 10 percent of those entitled to money. “In this case, we found almost 50 percent of the people,” he says.

An organization with an ongoing presence at the Turner egg farm is the Maine Migrant Health Program, which delivers onsite medical services to migrant and seasonal workers in a range of Maine farming ventures, from egg farming to apple picking.

Barbara Ginley ’88 is executive director of the Maine Migrant Health Program, which has an ongoing presence at the Turner egg farm. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

Over the last decade, MMHP director Barbara Ginley ’88 has involved a dozen students and alums, some directly from Bates, others through programs like AmeriCorps.

Ginley highlights two such projects that involved Batesies: one to evaluate the capacity of the DeCoster community to serve migrant workers’ transportation needs, and the other to create a resource guide to help foreign-trained healthcare workers transfer their skills to the U.S. workplace.

“The goal of both was to create greater capacity for independence within the farmworker community,” she says. “While we often advocate on issues like workplace safety, we also know when to get out of the way, so to speak.”

“What we were trying to show is, ‘Who needs factory farms?’” Haaz says. “All you really need are local eggs and family farms.”

In fall 2004, Sam Haaz ’06, Andrew Currier Stokes ’06, and the late Nate Dorpalen ’06 collaborated on a 20-minute documentary film about the DeCoster egg farm entitled Fowl Play.

Haaz, now a law student at Drexel University, recalls how he and Dorpalen were nearly overcome by the reek of ammonia when they sneaked into the DeCoster barns to shoot rare footage of the millions of laying hens packed so tightly into cages that they could barely move.

Jesse Laflamme ’00, manager of Pete & Gerry’s Organic Eggs, oversees an operation that’s the antithesis of factory farming. Hens live cage-free in open barns, lay their eggs where they wish, and have outdoor access. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

The documentary also features extensive interviews with local farmers. “What we were trying to show is, ‘Who needs factory farms?’” Haaz says. “All you really need are local eggs and family farms.”

Amen to that, says Jesse Laflamme ’00, manager of Pete & Gerry’s Organic Eggs, based in New Hampshire and one of the largest organic egg farms in the country. “We’re the antithesis of DeCoster,” Laflamme says.

“The irony is that I almost couldn’t go to Bates because DeCoster was putting family farms out of business.” By the 1990s, family egg operations were rapidly disappearing from the New England landscape, their big chicken barns often becoming winter storage for boats and cars.

But his family farm has rebounded, in part because of the growing awareness of the social and environmental evils of factory farming. “In a roundabout way,” Laflamme says, “Bates had a hand in the survival of our family farm.”

Nate Dorpalen ’06

Nate Dorpalen ’06, who helped to produce the Fowl Play documentary referenced in this story, died Oct. 8 in a hiking accident while backpacking on the Lofoten Islands in northern Norway.