How to Make the Universe Right: The Art of the Shaman in Vietnam and Southern China

January 24 – March 21, 2014

How to make the Universe Right presents an extraordinary selection of Shaman scrolls and an extensive array of ceremonial objects of the Yao, Tày, Sán Dìu, Cao Làn, Nùng, Sán Chảy, and other small population groups of Vietnam and southern China. The Yao, Tày, and related ethnic minority people originally lived in the mountains of southwestern and southern provinces in China. Due to extenuating political reasons, they and other tribal groups migrated to Vietnam during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and settled in mountainous regions of the north. The groups brought with them a rich tradition of shamanist practice that varies from group to group, Daoist for the Yao, and various amalgamations of primarily Daoist deities and rituals, but also Buddhist deities, aspects of Hinduism, Confucian ancestral worship, animism and other natural forces for others. The rich spiritual life of traditional culture and ceremonial practice is embodied in this exhibition. Together with the accompanying catalogue, How to make the Universe Right provides the opportunity to appreciate these important scroll paintings and other objects aesthetically, and to gain an understanding of the ritual life and its complex system of Shamanistic religious beliefs of the Yao, Tày, Sán Dìu, Cao Làn, Nùng, and other groups.

An exhibition of sacred objects from these groups and on this scale is unprecedented in the United States, and will further the understanding of these little known cultures in the west. How to make the Universe Right will be supported by an extensive illustrated catalogue written by Trian Nguyen, associate professor, Art and Visual Culture and Asian Studies at Bates College. In the catalogue, Nguyen discusses topics including how to become a shaman, religious ceremonial practice, painting scroll sets, shaman robes and garments, and ritual items. Nguyen provides an overview of shaman life and ceremonial practice among the various peoples, and details how to become a shaman, how shaman priests and priestesses use the scrolls and ceremonial objects to communicate directly with the spirits of the unseen worlds, exorcise evil spirits, bring prosperity for family, and provide a spiritual path for members of their villages and communities. He also describes the shaman scrolls, robes, musical instruments, and other ritual items in detail, and chronicles the religious and cultural stories that the deities, mystical creatures, and symbols depict in the paintings.

The scroll paintings represent a wide variety of artistic styles from highly refined to fairly archaic, and date from between the early 19th to mid/latter 20th century. Many may be regarded as masterpieces that provide primary sources for the study of history, culture and religion of the represented groups. Scroll painting sets vary in number from sets of three, which are used by young shamans to complete sets of seventeen or more, which are used in the most important ceremonies by shaman high priests and priestesses. Painting scrolls are revered as being inhabited by the depicted gods. The complete Daoist pantheon is usually represented, including the Three Pure Ones, the Jade Emperor, and Master of Saints. Depending the beliefs of the individual group, they may also include Buddhist Bodhisattvas, deities from Hinduism, and imagery representing Confucianism, animism, and ancestral worship. The spiritual stories represented in the scroll paintings also include celestial beings such as the Three Merciful Ones, the Four Heavenly Messengers, and the Ten Kings of Hell, and divine animals such as tigers, dragons, lion-dogs, and other sacred animals.

The scroll paintings, ceremonial costumes, masks, instruments and the other ceremonial objects represent an unbroken link to the past of Asian mountain cultures whose roots go back 2,000 years. Shamans lead their people’s vital spiritual life, binding them people together and helping them make the universe right by righting wrongs, communicating with the ancestors, and dealing with the unfriendly forces of nature and of surrounding larger group of outsiders.

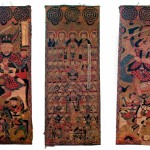

- Yao, Set of three Daoist Shaman Scroll Paintings, 1900, ca. 46 x 18 inches each

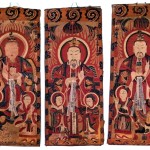

- Yao, Three Pure Ones, from a set of 17 Daoist Shaman Scroll Paintings, 1845, Ca. 44 x 18 inches each

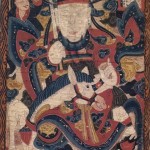

- Yao, detail of the Scroll Painting of the High Constable, from a set of 17 Daoist Shaman Scroll Paintings, 1845

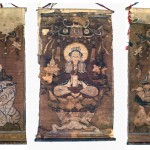

- Yao, Supplemental set of three Buddhist Shaman Scroll Paintings: Three Bodhisattvas: Samantabhadra, Avalokitesvara, Manjusri, ca. 19 x 10 ¼ inches each

- Yao, Shaman Robes

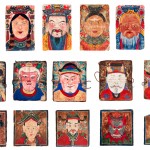

- Yao, Shaman Masks, wood, paper hair and mixed media

- Yao, Shaman Paper Masks, watercolor and ink on handmade paper

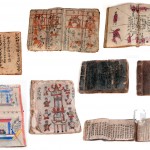

- Yao, Shaman Sacred Books

- Yao Musical Instruments

- Yao, Shaman Hats and Accessories

Press

Scene Magazine, February 20-February 26, 2015

Insite on Shaman Life

Santa Barbara Independent

Shamanic Art from China and Vietnam

Kolaj Magazine Issue #10

Something in the Water

Portland Press Harold, March 3, 2014

Art Review: ‘Art of the Shaman’ at Bates