Author John Edgar Wideman’s talk on Martin Luther King Jr. Day was less an occasional speech than a reading — a lyrical, personal, work-in-progress shared with several hundred listeners in Alumni Gymnasium.

The reading was about an image and a name — literal and metaphorical — that stays in Wideman’s mind. The image is the infamous black-and-white photograph, published in Jet magazine in 1955, of what remained of a Chicago teen-ager after a Mississippi lynch mob beat him to death and threw his grossly disfigured body into a river: one eye gouged out, a bullet in his skull, the side of his head crushed.

The boy’s name was Emmett Till.

“The name Emmett is spoiled for me,” said Wideman, who then continued: “Sometimes I think the only way to end this would be with an Andy Warhol-like strips of images. The same face. Emmett Till’s face replicated 12, 24, 48, 96 times on a wall-sized canvas, like giant postage stamps, end to end, top to bottom, each version of the face, exactly like the other, except different names printed below each one.”

The names would be, Wideman continued, “Martin Luther Till. Malcolm Till. Medgar Till. Nat Till. Gabriel Till. Michael Till. Huey Till. Bigger Till. Nelson Till. Mumia Till. Colin Till. Jesse Till. Your daddy. Your momma. Your sister. Brother. Aunt. Cousin. Uncle. Niece. Nephew…Till.”

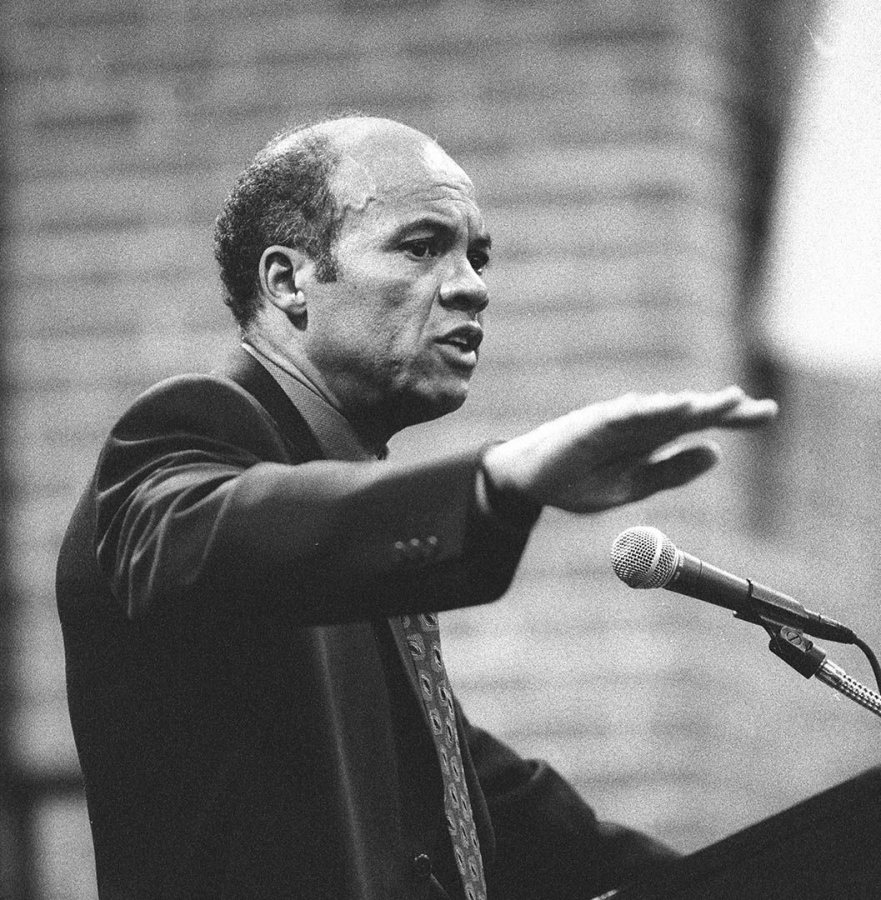

John Edgar Wideman delivers the keynote address, “Looking for Emmett Till,” at the Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance at Bates College on Jan. 18, 1999. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The face and name of Emmett Till — “the horrific death mask of his erased features,” Wideman’s metaphor for the unhealed wounds of slavery and racism — “marks a sight I ignore at my peril, a grievous wound, a wound unhealed because untended.

“Beneath our nation’s pieties, our self-delusions, our denials and distortions of history, our professed black or white certainties about race, lies chaos — the whirlwind that swept Emmett Till away and brings him back.”