Seventeen senior art majors exhibit work at college museum

Seventeen studio art majors at Bates College show work from their yearlong thesis projects in the annual Senior Exhibition, which opens with a 7 p.m. reception on Thursday, April 5, in the Bates College Museum of Art, 75 Russell St.

The exhibition runs through May 26 in the museum’s Bates Gallery. Admission is free. Regular hours are from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday.

For more information, please call 207-786-6158 or visit the museum website.

The Senior Exhibition artists are: Jacob Bluestone, Huntington, N.Y.; Alana Corbett, St. Helena, Calif.; Deanna D’Entremont, Biddeford, formerly of Kennebunk; Sarah Drosdik, Rangeley; Kelsey Engman, Haverford, Pa.; Alexis Grossman, Piedmont, Calif.; Julio Guevara, Brentwood, Md.; Nakeisha Gumbs, Brooklyn, N.Y.; Jenna Hoffstein, Southborough, Mass.; Taimur Khan, Natick, Mass.; Amelia Larsen, Concord, N.H.; Kate Liston, Newport, R.I.; Nels Nelson, Andover, Mass.; Irene Restrepo, Quito, Ecuador; Meg Reynolds, Rochester, N.H.; Julia Rice, Eau Claire, Wisc.; and Arlee Woodworth, West Bath. (See a slide show of exhibition images.)

Since its dedication, in 1986, the museum has maintained a special relationship with the college’s Department of Art and Visual Culture, expressed in part by its support of studio art majors through the annual Senior Exhibition.

As required by the major, those students create a cohesive body of related works through sustained studio practice and critical inquiry. The yearlong process is overseen by studio art faculty and culminates in this exhibition.

Bluestone uses photography to express his ideas on human-altered landscape and generic urban development. “I am fascinated by wide-open space,” he writes in a statement about his work. “Space is being engulfed throughout the United States by unbounded urban expansion at a rate that is expediting the death of a sense of place.”

Also a photographer, Corbett made images of different people wearing the same yellow dress. “We’re told that if we wear a certain dress or shirt it makes a specific statement about who we are,” she writes. “But what happens when a variety of people, all embracing their own individuality, wear the same thing? . . . Who changes what or what changes whom?”

D’Entremont is a painter fascinated by color and representational technique. “One color can look entirely different in different contexts,” she states. “My paintings are primarily an exploration of color and rely heavily on contrast and relationships.”

Drosdik uses grids and organic materials to create multi-panel paintings. “I am interested in the relationship between the rational grid and the happy accidents,” she says. “When they work, it makes me think about the calculated and the uncontrolled, and how they come together in each of our experiences.”

Engman paints oil still-lifes of organic forms such as flowers. “I have selected this subject matter, especially the flowers, mostly because of what they offer as a form, an organic shape that contains color,” she writes. “The setups that I paint from play a crucial role. I spend a long time choosing the elements in my still life and how they are juxtaposed.”

Grossman makes vibrant prints combining etching and monoprint techniques. “I have taken my fascination with color, texture and ornamentation and translated it into prints by layering color, pattern and line,” she writes. “I want my prints to have the qualities of lush and sensuous fabric that I surround myself with and work from.”

Guevara sculpts in clay. “Currently, my central interest is architectural forms and their relation to space,” he writes. “I approach creating these pieces as an adventure, not knowing what will come next, allowing myself the freedom to make mistakes.”

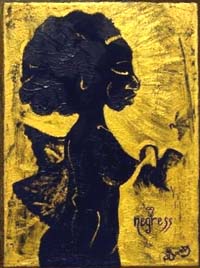

Gumbs is a painter exploring issues related to the African diaspora. Using Yoruba deities called “Orishas” as a key motif, she writes, “I create portraits and narratives about ‘divine’ characters in order to convey contemporary discourse on class, race, gender and sexuality. As a nonbeliever, I use images of the Orishas as an attempt to confront the African-American experience and its history of omission.”

Hoffstein uses computer graphics to comment on game worlds. “By exaggerating and parodying many aspects of these games . . . I am hoping to draw attention to the extent to which these elements diverge from their real-world counterparts,” she writes. “Considering exactly which elements of these virtual worlds make them so attractive may reveal interesting truths about our own world.”

In his site-specific installation in the museum stairwell, Khan uses large-scale drawings based on anatomy to investigate connections between external and internal, organic and geometric. “I want to encourage viewers to adventure through what may seem gross to some, in order to find the complex beauty of what is usually invisible, and literally inside of them,” he writes.

A photographer, Larsen is “experimenting with the idea of surveillance, with women being the primary object,” she explains. With a stylistic nod to film noir, she explores photography’s power to manipulate perceptions of reality and evoke a sense of story. “Cindy Sherman’s consideration of women’s roles in the media, the melodrama of Weegee’s crime scenes, and the mysterious blurriness in John Gossage’s photography continuously inspire me,” she says.

Using mass-produced and industrial materials, Liston constructs abstract shapes that refer to nature. “I don’t want to make ‘pictures’ of nature; I want to make pieces that embody the chaos and order I see in it,” she states. “Using nature as a model, I strive to accept and appreciate the accidents that happen and the order and chaos in my work.”

Nelson is a photographer examining the historic, largely unoccupied Bates Mill Complex and the boundaries between aesthetics and objective reality. “Representation in handmade images is illusory, but photographs . . . can be mirrors of specific times and places,” he writes. “These archival digital prints will be displayed in Museum L-A as a record of these spaces before their eventual renovation or destruction.”

Using paint and xerography, Restrepo follows her fascination with pattern by creating modular images that can be fitted together in countless ways yet remain readable. “Within this unlimited number of possibilities, I challenged myself to find one interesting and coherent design,” she states.

Influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, post-impressionism and German expressionism, Reynolds paints nude self-portraits. “In an age where pressure for physical perfection leaves a vast majority of people, including myself, with a distorted and unsatisfied view of their own bodies, painting these pieces forces me to contend with the disparities between the perceived and the actual,” she states.

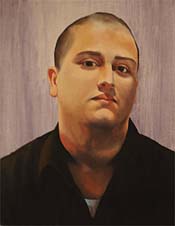

“For me, creating images is the most natural expression of my thoughts and emotions,” writes Rice. A painter, she tries to capture individual people. “It’s about making the paintings be more than accurate depictions of people — [making the art] feel like what it is to be with them,” she writes.

Woodworth is drawn to the gestural and visual power of handling paint. “Each painting is still an experiment because the color always feels new to me,” she states. “I am in the process of teaching my eyes to see color because that is what I am drawn to; how colors react and form relationships, how they contrast with each other and how colors make an object. I can spend hours just looking at a tomato.”