It's a Microworld After All

Gil Crawford ’80 could handle the heat and dust. It was the inequality of the situation that ripped at his spirit.

It was 1986, and Crawford was a volunteer helping to run a Red Cross famine-relief operation Chad. After the yellow and white relief trucks rolled into a nomadic camp and the hungry people gathered around, Crawford and his team would begin dropping 100-pound bags of grain on the baked ground.

In return, a tribesman might offer a goat. “I’d accept it, to put a modicum of dignity into the relationship,” Crawford recalls. Otherwise, the relationship “was grotesquely undignified. And it was a grotesquely inefficient way of solving a problem.”

The episode culminated Crawford’s disenchantment with traditional top-down foreign aid. It also stoked his drive to find a sustainable way to help people out of poverty.

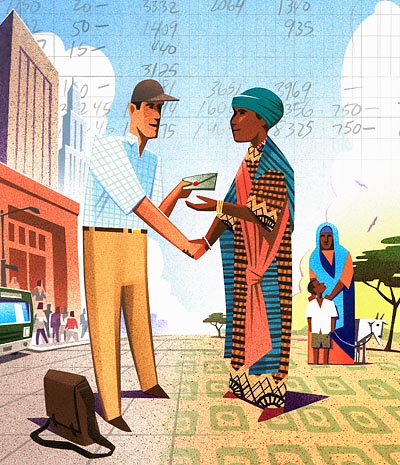

For Crawford, that quest ended in the 1990s as he embraced microfinance, often defined as very small loans (“microcredit”) given to entrepreneurs who otherwise aren’t “bankable” and can’t get traditional loans. The phenomenon is credited with lifting millions out of poverty worldwide.

“Microfinance is efficient, sustainable, and at its core a dignified relationship between the borrower and loan officer. It’s not one of a mendicant coming with a begging bowl,” says Crawford, who is now CEO of MicroVest Capital Management, founded in 2002 as the first U.S. firm to make private investments in microfinance institutions (MFIs) worldwide.

At the time of his sobering Red Cross experience back in 1986, in fact, Crawford was already prepping for a year-long international bank training program at Chase Manhattan. He owned a master’s in international studies from Johns Hopkins but knew that financial training was the key to his future economic development work.

“Gil was always a social-justice guy,” says fellow history major Rachel Fine Moore ’80, who worked with Crawford at Bates on such political-action issues as a fight against a bottle-bill repeal effort. “But I remember thinking how unusual it was for a social activist to know that he needed financial training to achieve his goals.”

Martin Fisher, a childhood friend and fellow social entrepreneur, explains that Crawford’s late father, a banker, helped shape his son’s faith in capitalism. “Gil is a humanist but also a strong believer that private-sector money and business models can help people on a large scale,” says Fisher, who recalls the game nights — involving Risk, chess, poker — that his friend organized back home in Ithaca, N.Y.

Gil Crawford

“He’s also got an intellectual curiosity,” Rachel Moore continues. “I’m sure he could party with the best of them, but there was a whole intellectual component to what he was about.”

That intellect, and a certain dogged constancy of vision, is apparent when one considers that Crawford’s career is a straight line from his honors thesis, in which he explained how Sweden avoided violent working-class unrest during its late–19th century transition to democracy. Crawford suggested that the existence of many small businesses (farming, lumber, minerals), scattered across the country helped the working class stay connected socio-economically. As he wrote in 1980, presciently, “the development of rural economies can temper the problems inherent in modernization.”

Though he credits Bates with teaching him to “really keep at something,” he’s always been a self-driven person. Take his tennis game. “I’m not the kind of guy who needs to force the ball down someone’s throat, but I do need to feel that I’ve played a good game.”

Crawford’s job is a bit ironic. He’s making money for wealthy investors, but that money comes from the world’s poor — the very people who Crawford wants to serve through microfinance. The cognitive dissonance hurts sometimes. “When I drive in from the Bogotá airport and see a family around a small fire, there’s a part of me that, even today, wants to ask the driver to stop so I can give them 50 bucks,” Crawford says. “That act would make me feel good, but it is not going to have any meaningful long-term impact.

“That’s what I struggle with in this work” — Crawford’s voice catches — “you dine in New York City with an investor who is enormously blessed with material wealth, and then travel abroad and experience the intrusion of poverty.”

Gil Crawford (left) visits Mongolia in 2004 to conduct due diligence on a microfinance institution, XAC Bank. At right is bank CEO Ganhuyag Ch.Hutagt; in middle are MFI clients. MicroVest made its initial investment in XAC, of $1.5 million, a few months later and has continued to provide financial capital since then.

This dichotomy is mirrored in a larger debate about the impact of private investment in MFIs. Ahlam Fakhar, a visiting professor of economics at Bates, explains why some say it’s a bad idea.

When MFIs emerged, they got their loan money from donor-driven entities focused mostly on the social impact. As MFIs matured, they proved profitable, which has attracted private capital from firms like MicroVest. For example, say an MFI in Tajikistan charges a microcredit rate of 35 percent. If the various costs of making that loan are 20 percent, then 15 percent is left over, which the MFI can use to pay for loan funds and still remain profitable.

But, Fakhar cautions, remember that microfinance emerged only because the private market failed to provide poor people with affordable credit. “I’m pro-market,” she says, “but if the market failed the first time around, how are you going to sustain social responsibility this time?” In other words, as global capital surges toward MFIs, they in turn might begin to exclude the riskiest — read poorest — clients once again.

Crawford disputes such scenarios: “Commercial microfinance can lift the largest number of working poor out of poverty.” The riskiest and poorest who seek loans, he says, should be served by donor-driven MFIs helping to “push the frontier of microcredit.”

Private investment in MFIs, he believes, is actually the key to sustaining the microfinance phenomenon. “What MicroVest is about — and I’m getting excited here — is creating institutions that are part of the financial tissue of these societies,” he says. “And not just for 10, five, or four years until some aid project is finished. “We’re about building institutions that are going to be around for 500 years.”

By H. Jay Burns

Illustration by Marty Braun