Five's the charm as Bates biochem major wows U.S. veterinary schools

Jennifer-Kate Linton, a Bates senior from West Redding, Conn., has achieved a rare distinction: She has been accepted by seven different postgraduate programs in veterinary medicine, including five in the United States.

Jennifer-Kate Linton, a Bates senior from West Redding, Conn., has achieved a rare distinction: She has been accepted by seven different postgraduate programs in veterinary medicine, including five in the United States.

Linton, who was accepted by two schools in Scotland in addition to the U.S. five, this fall will attend the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

One of only 28 U.S vet schools, Penn has “one of the most selective programs in the country,” says Lee Abrahamsen, associate professor of biology at Bates and chair of the college’s Medical Studies Committee.

“I was very surprised, actually,” by her application success, says Linton, a biochemistry major. But it was no surprise to Abrahamsen, who was Linton’s advisor on a senior thesis project involving antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

To get into a good veterinary program, “you need grades, good test scores and lots of experience — far more than is required up front for med schools,” Abrahamsen says. “They look for sensibility, the willingness to work hard and a solid dedication to the welfare of animals of all kinds.

“Jenn has all of those things and then some.”

Linton’s visit to Penn revealed an educational style that struck her with its similarities to Bates. “It’s a lot about using your peers as assets, which is something that I’ve definitely experienced at Bates,” she says. “Especially within the sciences — you get so close to your lab partners and your peers that you’re working with. It seems like Penn fosters a similar community.”

Linton has had a busy time at Bates. She played volleyball all four years and this past season was team co-captain with Brittany Clement. She has also been a residence coordinator and a Bates Buddy, mentoring elementary school pupils.

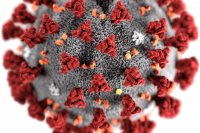

For her thesis, Linton wanted to work with bacterial DNA and to include a community service piece. She decided to explore an issue of increasing concern to the medical establishment: the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria.

Garden-variety S. aureus is a common bacteria that under certain circumstances can cause serious but easily treated infections. But MRSA, invulnerable to the antibiotics usually used to fight these infections, is much more of a health threat.

Dogs and other animals can carry an organism related to MRSA called MRSI — methicillin-resistant S. intermedius. Linton undertook to determine whether MRSI from dogs could genetically transfer its antibiotic resistance to normal, nonresistant S. aureus.

Taking a volunteer position at a local animal shelter, she used exercise periods with her canine charges to collect bacteria from their noses with a swab. Back in the lab, she grew the bacteria and exposed them to an antibiotic to test the organisms’ resistance.

Surprisingly, all her cultured bacteria showed substantial resistance to a range of antibiotics — including vancomycin, a “last-resort” drug for treating MRSA. Forty percent of the dogs carried vancomycin-resistant bacteria.

“That was a little worrisome,” Linton says.

The next step of her research involved nonresistant S. intermedius. Linton used two different techniques to expose the bugs to the MRSA genes responsible for drug-resistance. Again, her findings were eye-catching.

In one method, S. intermedius were exposed to genetic material from dead MRSA; in the other, to live MRSA. In both processes, the previously vulnerable bacteria took up the relevant genes and developed antibiotic resistance.

“It’ll be interesting to see what the implications of this are,” Linton says. “The results I got were surprising and a little scary, but they were really good, so we’re actually thinking of publishing” the research in a scientific journal.

Linton, whose experience includes spending last summer working the late-night emergency shift at MSPCA–Angell Animal Medical Center in Massachusetts, has wanted to be a large-animal vet since age 5. “I’ve always loved animals and I’ve always had a really good relationship with them,” she says.

And she relishes the investigative aspect of the work that arises because animals can’t explain how they feel or what they’ve been doing that may have hurt them. “It’s like being a detective and a doctor combined,” she says.

![]()