Stairway to Heaven exhibit exploring Chinese cityscape, soon to close

Closing Dec. 13 is a major photographic exhibition at the Bates College Museum of Art offering alternative perspectives on the intriguing, dynamic Chinese cityscape. Stairway to Heaven: From Chinese Streets to Monuments and Skyscrapers showcases work by 17 Chinese artists who examine how economic reform, a new influx of personal wealth and rapid industrialization have changed the urban environment.

Open to the public at no cost, the museum is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday. It is closed on major holidays. For more information, please call 207-786-6158 or visit the museum Web site. The museum is located at 75 Russell St.

Including sculpture and video as well as still photographs, Stairway to Heaven uses street life, the proliferation of skyscrapers and the shifting meanings of historic monuments as avenues for exploring China’s stunning transformation during the past three decades.

That transformation, fascinating for students of China, has come hand in hand with a flowering of the visual arts that is just as compelling for observers of the art world, says Mark Bessire, director of the Bates museum and co-curator of the show.

“What’s so interesting is watching a culture that wasn’t allowed to be creative for so long suddenly explode with creativity, and watching artists try to figure out what their role is,” Bessire says.

Showing simultaneously is Flourishing Folk: New England Decorated Works on Paper and Document Boxes from the Deborah N. Isaacson Trust. The Bates museum is one of 11 in Maine to display folk art from their collections this year in a cooperative effort marking the introduction of the Maine Folk Art Trail. The project includes a book published by Down East Enterprise and a symposium that Bates will host in September.

In the context of the 2008 Beijing Olympics and China “projecting itself to the world from the government’s standpoint, it was great to have contemporary art to offset the ‘official’ position,” Bessire says.

Stairway features artists in all stages of their careers — including such stars of the contemporary Chinese scene as Ai Weiwei, Hong Lei, Ma Liuming, Xing Danwen and Zhang Dali. What they all have in common is the imperative to interrogate a China that is remaking itself literally from the ground up.

Historic neighborhoods, with their long traditions of street life, are making way for forests of skyscrapers. Western materialism is supplanting communist doctrine and ancient social traditions. And the government, in a 180-degree turn from Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, is cautiously embracing contemporary art.

“The biggest change is that the government now actually sees the artists as being beneficial for the greater good in the long run,” Bessire says. “But the flip side could be that next week some artist does something around the Olympics and gets put into jail. That’s the part you can’t predict.”

As photographer Ai Weiwei considers the role of historic monuments in his culture and others, his response is a photo series offering a one-fingered salute to such icons as the White House and the Eiffel Tower along with Tiananmen Square.

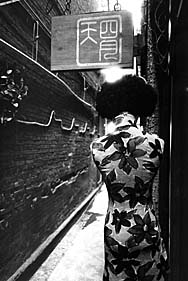

Shanghai-based photographers Liang Weiping and Gu Zheng (who curated the 2004 exhibition Documenting China for the Bates museum) use stark black and white prints to convey the grinding contrast between the new China and the remnants of the old.

Others take a more formal approach. Luo Yongjin’s Gas Station Series pays homage to flamboyant, one-of-a-kind stations that are now being replaced by cookie-cutter replicas of facilities found around the world.

One of three women showing work in the exhibit, Xing Danwen uses manipulated color images to suggest the sterility of life in high-rise, controlled-access urban residential developments. “The dark side of the new ‘heaven’ in the skies may in fact be alienation and despair where the utopian ideals of the collective are erased,” Bessire writes in his introduction to the exhibition book.

And in some of the show’s most surprising work, Yang Yongliang uses digital technology to combine images of skyscrapers and construction cranes into striking adaptations of the traditional ink landscape painting form.

Bessire traveled to China twice, in 2004 and 2005, to scout out work for the show — seeing some 300 artists all told, he estimates. These days, he says, the progress of the Chinese art scene is like a dream come true for the art historian or curator. “In one generation, it went from nobody knowing there was contemporary art in China to its now being the hottest art market in the world.”

“It’s like this mini-art history lesson,” where five millennia of artmaking gave way to art as state propaganda, followed by the Cultural Revolution and its near-obliteration of art. And then, with the economic reforms that started in the late 1970s, the bottle was shaken and the cork pulled out.

“And the artists got with it really quickly,” Bessire says.

Bessire co-curated the show with Raechell Smith, a regular collaborator who directs the H&R Block Artspace at the Kansas City Art Institute. A book published by University Press of New England will accompany the exhibition.