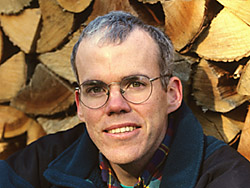

Author McKibben and key figure in 'renewable energy island' to speak

On March 12 and 13, two decisive actors in the effort to curtail global climate change offer back-to-back talks at Bates College.

Bill McKibben, the environmental journalist who wrote the first book aimed at a general readership about climate change, gives a talk titled “Global Warming: Fighting Against It, Living With It” at 7:30 p.m. Thursday, March 12, in Chase Hall, 56 Campus Ave.

Sören Hermansen, named one of Time Magazine’s 2008 Heroes of the Environment for his leadership in a Danish island’s conversion to fully sustainable, carbon-neutral energy, speaks at 2:45 p.m. Friday, March 13, in Keck Classroom (G52), Pettengill Hall, Alumni Walk.

Both events are open to the public at no charge. Sponsored by the Harward Center for Community Partnerships at Bates, the McKibben event is part of the series “The Civic Forum: Maine in a Transnational Age.” For more information, please call 207-786-6202.

The Hermansen event is sponsored by the Program in Environmental Studies at Bates. For more information, please call 207-786-6490.

McKibben is an American environmentalist and journalist who writes about global warming, alternative energy and the risks associated with human genetic engineering. His first book, The End of Nature (Random House, 1989), is regarded as the first book for a general audience about climate change, and has been printed in more than 20 languages. Several editions have come out in the United States, including an updated version published in 2006.

In late summer 2006, McKibben helped lead a walk across Vermont to demand action on global warming, a demonstration that some newspaper accounts called the largest to date in America about climate change. He founded Step It Up 2007, an organization advocating that Congress enact curbs on carbon emissions that would cut global warming pollution 80 percent by 2050. With 1,400 global warming protests in all 50 states in April 2007, Step It Up 2007 has been described as the largest day of protest about climate change in U.S. history.

McKibben’s second book, The Age of Missing Information (Random House, 1992), is an account of an experiment: He collected everything transmitted on the 100 channels of cable TV on the Fairfax, Va., system (at the time among the nation’s largest) for a single day. He spent a year watching the 2,400 hours of videotape, and then compared it to a day spent on the mountaintop near his home. This book has been widely used in colleges and high schools, and was released in a new edition in 2006.

Subsequent McKibben books have explored the Book of Job and the environment; human population; and what he sees as the existential dangers of genetic engineering. Deep Economy: the Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future (Times Books, 2007) addresses shortcomings of the growth economy and envisions a transition to more local-scale enterprise.

A scholar in residence at Middlebury College, McKibben lives with his wife and daughter in Ripton, Vt.

Since 1997, Sören Hermansen has led the 4,300 inhabitants of the Danish island of Samsø, where he was born, away from dependence on imported fossil fuels and toward sustainable, carbon-neutral energy use. Once reliant on oil for heat and coal for its electricity, island residents today heat their buildings with solar and geothermal technology and island-grown straw, and produce enough electricity from the wind that Samsø is a net exporter of electricity.

In 1997, Denmark’s government announced a renewable-energy contest challenging communities to show that they could live without fossil fuels. As leader of the Samsø Energy and Environment Organization, Hermansen persuaded his fellow islanders — through gentle coaxing, persistence and occasionally, free beer — to make the difficult changes in mindset, technology and lifestyle that would free the island from its fossil-fuel addiction.

Hermansen had a hand in the adoption of myriad sustainable technologies around the island, from wind turbine construction, to solar heat and electricity, to the use of biomass grown on the island, such as straw and wood chips, for residential heating.

The islanders “formed energy cooperatives and organized seminars on wind power,” writer Elizabeth Kolbert reported in “Island in the Wind,” an article about Samsø in the July 7, 2008, issue of The New Yorker. They supported the construction of wind turbines on the island and offshore.

“They removed their furnaces and replaced them with heat pumps. By 2001, fossil-fuel use on Samsø had been cut in half. By 2003, instead of importing electricity, the island was exporting it, and by 2005 it was producing from renewable sources more energy than it was using.”

While some island residents continue to run their vehicles on fossil fuels, the island’s wind-generated electricity offsets the carbon produced by vehicles. Samsø shows that renewable energy can directly benefit its users through more than just moral satisfaction, too, as shareholders in some of the wind turbines receive dividends from the sale of power.

“We always hear that we should think globally and act locally,” Hermansen told Kolbert. “I understand what that means — I think we as a nation should be part of the global consciousness. But each individual cannot be part of that. So ‘Think locally, act locally’ is the key message for us.”

Today, as director of the Samsø Energy Academy, Hermensen has told the story of Samsø at conferences around Europe and in Asia, as well as the United States.