A Place We Can Talk

In Alex Dauge-Roth’s Short Term course, students learn with, not from, orphan survivors of the 1994 genocide

By Simone Path ’11, with Associate Professor of French Alex Dauge-Roth

One must know and see, one must see and know. Indissolubly. — Claude Lanzmann, director of Shoah

In Rwanda, drenching rains can quickly turn the red dirt roads into barely navigable mazes of rocky protrusions and gorges pooling with mud. It was after one such downpour last spring that I began to confront what I am made of, physically and psychologically.

In country, each Bates student was paired with a member of Tubeho, the organization of orphan survivors of the genocide. Together, they negotiated how to move forward with interviews and oral histories. Pictured here are Innocent Micomyiza and Morgan Lynch ’10.

I saw before me an exhibit of human bones, arranged by leg, arm or skull, starkly displayed against a dark blue background. Only 15 years ago, those bones gave form to living bodies, like my own, full of hopes and dreams. Then came April of 1994, when one of the final genocides of the 20th century rapidly unfolded, leaving some 800,000 people, mostly Tutsis, slaughtered in just 100 days.

My encounter with human bones occurred last May at the Gisozi Memorial in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. At this memorial and others like it, visitors are reminded how the world turned away — yet again — during a genocide. Fixated on the dead bones, I was determined not to look away, even as I heard the sobs of a few Rwandan survivors who would become my friends and the sniffling of a fellow Bates student nearby.

I was among 13 Bates students, all women, who had arrived in Kigali to begin the off-campus portion of our Short Term course “Learning with Orphans of the Genocide in Rwanda,” taught by Associate Professor of French Alexandre Dauge-Roth.

The orphans we would learn from are members of Tubeho — the word means “let’s live” in Kinyarwanda — an association that since 2000 has brought together more than 300 orphans of the genocide to live in a Kigali neighborhood. They live in “reconstituted” families, groups of four to six genocide survivors who have lost their siblings and parents. In each family, one orphan is elected as the head of the household and acts like a parental figure for the others.

During our three-week stay in Rwanda,each Bates student was paired with a French-speaking member of Tubeho who was, in most cases, a student with aspirations similar to ours. We would conduct interviews with our Rwandan peers; they would choose how the interview would be conducted: video, audio, or in writing. We Bates students would submit our questions ahead of time for consideration by the orphan survivors.

The challenge of conducting oral histories was, Pathe writes, “to create a safe space for dialogue, where initially no such space existed.”

We were fortunate that Professor Dauge-Roth, in researching the personal, literary, and film narratives created since the genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda, had established strong connections with Tubeho, so we were not total strangers to them. Still, the expectations were great considering the short time we would be in country, just three weeks. We would not simply be learning about our hosts from a clinical distance. No, we would be expected to learn with them by becoming emotionally close to them. We would be expected to create a safe space for dialogue where initially no such space existed.

We gradually developed a sense of when to ask questions, when to shut up and listen, and when to put the genocide completely aside.

To accomplish this goal, the Bates students and orphans would have to carefully and reciprocally redraw the boundaries that separated our communities. But this was easier said than practiced.

At one exhibit at Gisozi that showed snapshots of victims when they were alive, I watched as my Rwandan “brother” Eugene examined the backs of each photo. I was looking at the fronts of the photos — images of newlyweds, a father holding his first son, a young driver standing beside a shiny red car — trying to digest the fact that all these innocent people were dead.

That fact was not news to Eugene, however. He was searching for connections. He was looking for names, dates, and places written on the back of the photos. These faces could have been his friends, family, teachers, or neighbors. Though I was physically close to him, I felt so removed from his experience. I did not know whether to stay while he turned over every photo, or to give him space, leave, and go on to another exhibit.

Our struggle to establish a dialogue about the genocide was easier once we recognized, respected, and became comfortable with the gap that existed between our vastly different experiences. We gradually developed a sense of when to ask questions, when to shut up and listen, and when to put the genocide completely aside. We took our cues from the Rwandans, soon realizing that every moment would be different for every survivor. Some went on at length about seeing known killers walk free in Kigali yet were reluctant to talk about their own pasts.

Two survivors, Pascal Mucyo and Ildephonse Majyambere, were able to give oral testimonies at genocide sites where friends and relatives had been slaughtered. In a school located in Nyange, near Kibuye, Ildephonse delivered a powerful testimony in the very classroom where students were killed. Others, meanwhile, reserved such personal details for one-on-one interviews with their American sisters, far away from onlookers.

We traveled often during our stay, and on these long rides our small, crowded red bus became an unexpectedly dynamic classroom. Conversation — not music from iPods — filled the time, and the passing countryside prompted memories, like the recollections of a survivor who described his month of walking and hiding on the very roadway we were on.

Near the end of our second week, we traveled overnight with one Tubeho member to the Murabi Genocide Memorial, a former school in the southern region of Butare where 50,000 people were massacred. As was the case at all of the memorials we visited, we were the only visitors. Only the frequent bleating of goats and cawing of crows punctuated the silence.

To help prepare us, Professor Dauge-Roth showed us photos and video footage he took in 2006 of what we would witness. But I doubt anything could have prepared me for standing in a building filled with bodies. Preserved with white lime, they lay close together on large metal platforms in 10 separate rooms. Amid the chaotic but recognizable bodily contortions — mouths open as if in mid-scream, hands raised to shelter their heads, mothers clutching babies, and women with legs sprawled and underwear around their knees — pain and resistance were visible.

Some of us sobbed. Some were so stunned that tears were too much to ask for. Two older women, both survivors working as gatekeepers of this memorial site, escorted us around but they did not speak French, nor did they respond to the few phrases we tried to pronounce in Kinyarwanda. Instead, at the end of the visit, they embraced each of us, holding us for a long time, as if making sure we would be all right before sending us on our way. That day signified an inversion of the roles we had expected to play: We were suffering, and the survivors were comforting us.

In our final meeting as a group, Batesies and survivors, we discussed what to do with the testimonies our encounter had generated. The orphans were rightly concerned about how their testimonies would be used. Because we were there to learn with them, the answer to that question would flow from their needs and desires.

So we broke into two groups. The Tubeho members decided to ask us to create a Web site to make visible their needs and the challenges they face. A website would mean unprecedented social visibility for a group that, by their very definition as orphans, do not often have such a voice.

On the Bates side, we discussed the questions we wished to address in our final papers. We decided to write about what we learned about ourselves, how our understanding of the genocide had changed, and how we would share what we learned.

The last question haunted us. Even before returning, we all fretted about how to answer the dreaded question from our friends: “How was Rwanda?” Sharing all the details of an intense experience, we learned, can sometimes just devalue it.

Still, we needed to talk. Some people were receptive, like my dad, who had consumed all the information about Rwanda and the genocide that he could get his hands on, and my friends, who were genuinely interested. Others implied that they were not interested in hearing anything too upsetting.

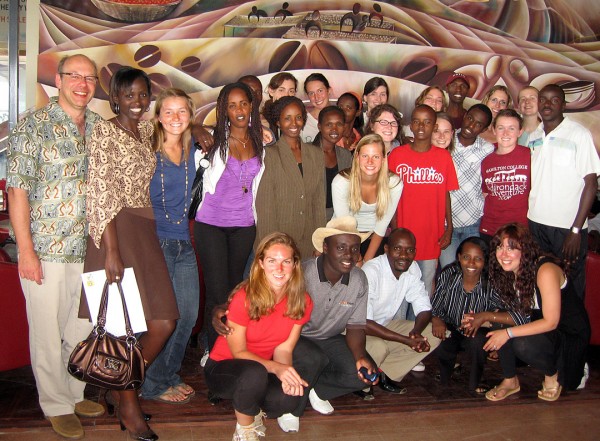

Alex Dauge-Roth (left) and his Bates students gather with their Tubeho partners at the Kigali airport at the conclusion of their visit.

True, we cannot force our experiences on anyone. But by not hearing the full story about humanity’s worst moments — whether it’s Rwanda in 1994 or Nazi Germany 70 years ago — these people will miss the significance of what most surprised us, the ones who listened: the hopefulness of the survivors.

These hopeful members of Tubeho, with whom we shared those long bus rides, morning jogs, and impromptu dance parties, welcomed us into their homes and trusted us with their stories. In return, I hope we showed them equal trust: that they, their country, and the bond that unites all of humanity, which many of them spoke so eloquently about, will not be forgotten.

In the end, that’s what we created in Kigali last May — a pure, shared space of hope. Our responsibility now is to nourish this space, remaining vigilant and creative in the present while remembering the horrific places from which these survivors have bravely traveled.

Simone Pathe ’11 of Madison, N.J., is a Dana Scholar and politics major. Alexandre Dauge-Roth, associate professor of French, won a 2009 Maine Campus Compact award for successfully infusing public service and civic engagement into his teaching. He is president of Friends of Tubeho.