The Right Questions

Wagner’s peace psychology journal adds to the discussion about torture and interrogation

On Day 2 of his presidency, Barack Obama signed an executive order effectively banning controversial prisoner interrogation techniques — such as waterboarding — and emphasized the proper and effective way for military and CIA interrogators to do their job: by following the U.S. Army Field Manual.

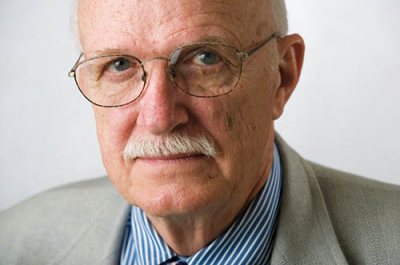

The news felt like a victory of sorts for Professor Emeritus of Psychology Dick Wagner, co-editor of Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. In November 2006, with support from Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Wagner helped convene a weekend meeting of four retired Army interrogators and seven research psychologists at Georgetown University. The two groups picked each other’s brains, candidly talking about interrogation, torture, and psychology.

“What we also found out was that these guys felt that the whole interrogation system was broken.”

The weekend’s findings were published as 10 articles in a special issue of Peace and Conflict called “Torture Is for Amateurs” in late 2007. The articles, Wagner says, shed light on proper interrogation techniques and, importantly, added to the public discussion about torture during the pivotal months leading up to the 2008 presidential election.

The Army interrogators, who’d seen their profession take a beating especially after the Abu Ghraib scandal, came to the table in 2006 for a few reasons. Mostly, they wanted to reject torture as an interrogation technique (as does the Army Field Manual, very specifically).

“What we also found out,” says Wagner, “was that these guys felt that the whole interrogation system was broken.”

Beginning in the late 1980s and mostly due to cost-cutting, the military began to de-emphasize “human intelligence collection” (interrogation and espionage) in favor of high-tech intelligence gathering through satellite imagery and communications interception. But after the 2003 Iraq invasion, the Army needed interrogators, fast, and began whisking 1,000 soldiers per year through a pared-down training program.

Young and immature interrogators are more likely to use “fear-up” tactics.

The trainee interrogators, typically 19-year-old high school graduates, were no longer chosen for intelligence and language ability and no longer received extensive mentoring. As a result, say Peace and Conflict co-editor Jean Maria Arrigo and former interrogator Ray Bennett (a pseudonym), these young and immature interrogators, with still-raging hormones and less-developed impulse control and psychosocial skills, are more likely to use “fear-up” tactics to scare information out of prisoners. Amateurs use such tactics, said the interrogators. Worse, they’re a step toward torture.

Instead, Army interrogators use non-abusive relational techniques that reflect the most basic theories of social psychology (persuasion, group dynamics). A prisoner “wants to talk,” said one interrogator. “It’s my job to become the person he wants to talk to.” Yet to apply these tactics skillfully, interrogators must have some degree of sophistication in “linguistic expertise, cultural sensitivity, flexible thinking, self-mastery, and the capacity to empathize with foreigners and enemies,” wrote co-editors Wagner and Arrigo.

Indeed, the older interrogators that Wagner met in 2006 were mature experts who knew how to charm the psychologists. “They are phenomenal at interpersonal relationships. They know exactly how to tune into you and make you comfortable,” Wagner says. “They were wonderful. We liked them all.”