Folks Back Home

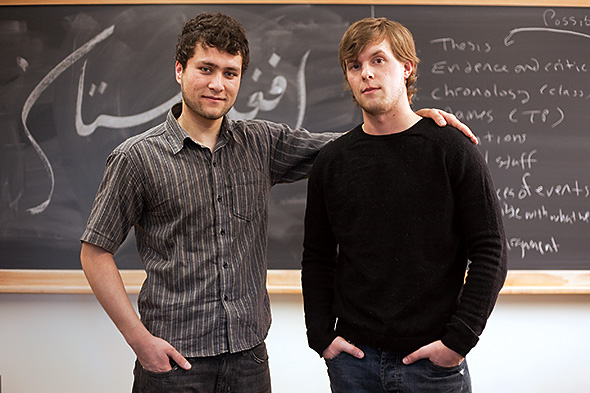

A Kabul resident and a Marine veteran agree that education is key for Afghanistan — and for Americans who want to help

By Doug Hubley

Back home in Afghanistan last summer, Mustafa Basij-Rasikh ’12 found that “democracy” means different things to different people.

Not always good things.

After decades of having democracy defined for them by such champions of the concept as the Soviets and the Taliban, many Afghans harbor “this preconceived notion, orally passed from generation to generation, that democracy is not good,” says Basij-Rasikh, who worked for an organization providing civic education programs.

“People hold on to that. And that just comes back to lack of education.”

But similarly, Basij-Rasikh and his good friend, Jared Golden ’11, a Marine veteran who served in Afghanistan, also see how the American perception of Afghanistan is defined more by what we don’t know than what we do.

“What’s missing from the equation is an effort to really understand Afghans and listen to them,” says Golden. “We love the quick fix and the quick answer. And it’s not that simple.”

“The only factor that can overcome adversity in a country is education.”

The College’s first Afghan student since at least 1984, Basij-Rasikh comes from a country where more than 70 percent of the population is illiterate. Yet this Kabul resident is a scion of what he terms “an unusual liberal family” that’s not only willing, as many Afghans are, but able to give its children good educations.

Three sisters are also studying in the United States. “My upbringing always reinforced this notion that the only factor that can overcome adversity in a country is education,” says Mustafa, a 21-year-old politics major. “I have a dream that my generation will be the generation who will solve the ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan.”

His dream is all the more moving because Basij-Rasikh and other Afghan students in the U.S. are supported by the Peter M. Goodrich Memorial Foundation, founded by Sally and Don Goodrich, whose son Peter ’89 died in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. And for all concerned, Mustafa’s presence at Bates seems to personify Peter’s legacy.

Golden, meanwhile, grew up in Leeds, a town near Bates, but applied here only after his Marine Corps service, which took him to Afghanistan in 2004 and Iraq in 2005–06. An infantryman, he spent much of his Afghanistan tour in Kunar province, a hotbed of insurgent activity.

“Four years in the Marines was enough to make me realize the importance of education, and I just love it,” says the 27-year-old Golden. Coming from homes 6,500 miles apart, the Afghan student and the American student of Afghanistan have arrived at much the same place in their thinking about education’s role in rebuilding that country. But for a deeply conservative nation, after three decades of war, education is by no means a given.

“People are more familiar with the gun than the pen,” says Basij-Rasikh. “Some people are making a life of this war because they are good at that. And if you are good at that you’re not going to give it away unless somebody gives you an alternative.”

The alternative of universal education could provide ethnically diverse, tribally oriented Afghanistan with common principles to rally around, says Don Goodrich. Especially in rural areas, the Taliban have exploited people’s piety by imposing a politicized interpretation of Islam. With universal education, says Basij-Rasikh, “people who manipulate Islam would no longer be effective, because everybody could read, everybody could write, everybody could think critically and they would question them.”

“Ultimately education is everything in Afghanistan,” agrees Golden. “That’s likely to change the situation in Afghanistan in the long run much more than war can.” He adds, “Their younger generation now is a big sponge — they just want to suck up education, they love it.”

Here at Bates, Basij-Rasikh and Golden have also found some teachable moments as they’ve encountered stereotyped beliefs about both Afghans and the Americans involved in their country. Golden rejects such stereotyping. To him, “all people should be understood and approached as individuals.”

“Get as many different perspectives as possible. Don’t just jump on a bandwagon or make assumptions.”

He adds, “I’m really always trying to paint the picture from both angles. I can see Afghans who do appreciate our being there, who feel better that the Taliban no longer runs their area or who love the fact that their child is going to school. And I can also see that that same family has lost five or six family members to U.S. air support.”

He adds that at Bates, “some people, I’m happy to say, don’t really associate me with my military experience anymore.”

Drawn together by their common ties to Afghanistan, Golden and Basij-Rasikh have much else in common. Among other things, Golden jokes, “we like food and are both good at spending money.” More seriously, “we are both big thinkers and share similarly ambitious goals and dreams. And I believe we share similar values and ethics.”

Summer 2009 found them both contributing to education in Afghanistan, Basij-Rasikh with the NGO Counterpart International, and Golden in Kabul with the School of Leadership, Afghanistan, or SOLA (Pashto for “peace”), which receives support from the Goodrich Foundation. Both hope to return this summer: Golden to work for a shipping company and Basij-Rasikh to pilot a program offering occupational support to people disabled by landmines.

“I can’t tell people what’s necessarily right or wrong in Afghanistan,” Golden says. “You have to do your research and get as many different perspectives as possible. Don’t just jump on a bandwagon or make assumptions.

“I’m just trying to go there and find ways to make a small difference.”