Heavenly Harvest in Nepal

• Click the thumbnails below to view the slide show

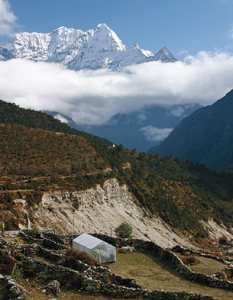

Nepalese villagers use high-altitude greenhouses to supplement centuries-old farming practices

Photographs and text by Judson Peck ’11

My plan was simple. The execution was tricky.

I would take a small plane into the Khumbu region of Nepal, then trek alone without guide or porter into Sagarmatha National Park, the highest mountain ecosystem in the world. Then I would settle into a village to research the plastic greenhouses used by Sherpa villagers to grow and harvest vegetables during the long, harsh winter.

My first challenge: Where the heck were these greenhouses? It’s not like they dot a Google map.

I had spent the previous few months in Kathmandu with the School for International Training, part of my Bates Junior Semester Abroad program. There, I learned about Nepal’s history, politics, culture, and development issues. Then I began my independent study project. This was last November.

I knew the greenhouses were up there — somewhere — deep in Sagarmatha National Park, which encompasses part of Mount Everest (“Sagarmatha” is the Nepali name for Everest).

And I knew that the greenhouses had been donated to villages within the park as part of a program that compensates villages for the fact that the area’s tightly restricted natural resources are off-limits. But no one had done much research on how they were being used and their effect on these tight-knit communities.

So I trekked around to different places like Namche, Khumjung, Khunde, and Thame. Then, at 12,000 feet, I discovered the village of Thamo, sitting on a plateau against the rocky mountainside, home to about 35 households and 10 donated greenhouses that were flown by helicopter from Kathmandu.

The growing season had ended by my November visit, and Thamo in November is much like Maine in late fall — on the brink of winter. But even in the coldest weather and climates, from the Arctic tundra to the high mountains of Khumbu, only the growing season is limited. As anyone who’s thrown an old bedsheet over tomato plants before a cold September night knows, you can extend the harvest season by creating a warm and protected microclimate.

The growing season had ended by my November visit, and Thamo in November is much like Maine in late fall — on the brink of winter. But even in the coldest weather and climates, from the Arctic tundra to the high mountains of Khumbu, only the growing season is limited. As anyone who’s thrown an old bedsheet over tomato plants before a cold September night knows, you can extend the harvest season by creating a warm and protected microclimate.

The donated greenhouses that create this microclimate at 12,000 feet feature thick, clear plastic that has been UV-stabilized so it won’t disintegrate. To withstand the mountain winds, the plastic is firmly attached to metal poles.

At dawn I sometimes woke to the clanging of bells as yak caravans plodded beneath my window.

In Thamo, I stayed at a guesthouse of the sort typically used by trekkers. As the sole guest most of the time, I was treated like family. I chatted in Nepali with the children about their schoolwork and ate daal bhaat — a traditional dish of rice and a kind of lentil soup — with the mother in the kitchen (the father worked at a nearby hotel and was away much of the time).

At night, my bedroom went well below freezing; most evenings I’d snuggle into my sleeping bag, wearing my winter jacket, and do my reading, like Four-Season Harvest by Eliot Coleman, who farms in Harborside, Maine.

One night I lay awake listening to the chants of four monks reverberate through the cold house as they blessed the family for the coming year. At dawn I sometimes woke to the clanging of bells as yak caravans plodded beneath my window carrying loads of woolens and knock-off North Face jackets from Tibet.

Every morning I trudged outside and broke the ice in the water bucket, then washed my face in freezing agony before the sun steamed it off my head. I didn’t bathe during my stay, partly because the bathing area was being used to hang drying meat and partly so I would fit in with daily life in the mountains.

I’d hoped to use my broken Nepali to interview the villagers but soon learned that they mostly speak Sherpa. I soon found a translator: Nawan, a trekking guide who has summited Everest himself.

As Nawan and I went from home to home, I learned that Sherpa culture demands that tea be served to visitors. Lots of tea meant many bathroom breaks but the tea-drinking sessions also fostered a relaxed setting for informal discussions.

On my last day in the village, a festival inaugurated the new village shrine. Among the rituals is placing yak butter on the men’s knives, khukuri, as a blessing and waving bamboo shafts with silk scarves attached. Four monks beat drums as the villagers chanted and drank raksi, a traditional and really strong distilled drink.

Afterward, there was dancing, then we staggered home over the rough terrain, knives in hand.

To New Heights

Some conclusions from my stay in Thamo, where high-altitude greenhouses have literally taken gardening to new heights:

• In the villagers’ traditional outdoor gardens and in the greenhouses, they grow mostly green leafy vegetables: lettuce, spinach, Chinese cabbage. During the June-September monsoon season, they grow everything from chilies and tomatoes to beans and squash.

• The greenhouses do save villagers money by producing inexpensive vegetables. But most of the food is eaten by families, so not enough is left over to sell in nearby Namche for income, as was hoped by the agencies that donated the greenhouses. (Still, it’s a big benefit to have year-round veggies.)

• My sense is that the greenhouses have not changed existing social or gender roles, as the women still do most of the gardening. The men often porter goods or guide trekkers, as Thamo is near the gateway to Mount Everest.

• Garden pests are a problem during the monsoon season. To combat pests, growers should improve the soil, since pests feast on weak plants. The growers already sweeten the acidic soil with wood ash, eggshells, and bone meal, but should also spread more compost and introduce “green manure”: plants that protect the soil and add nitrogen.

Environmental studies major Judson Peck is from Topsham, Vt. For his senior thesis in 2010–11, he will try to determine the political and environmental factors that create food scarcity in Nepal.