Open to the World: In stories and statistics, Sen. Mitchell sums up worth of higher education

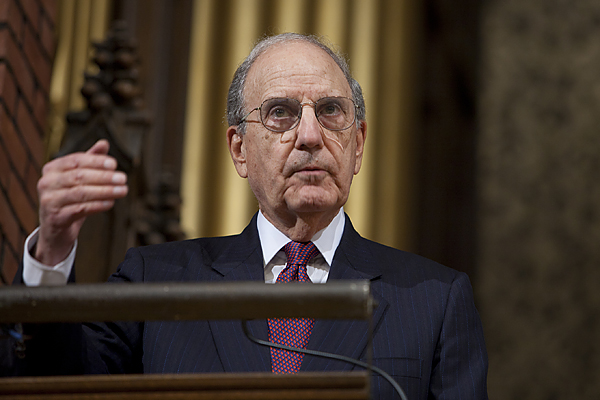

Former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell offers the keynote address during the “Open to the World” events on Oct. 27. Photograph by Rene Minnis.

Sharing the Chapel chancel with 15 Bates students supported in their studies by a statewide program that he founded, former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell used incidents from his own life to drive home higher education’s value to both personal growth and economic success.

Praising Bates as a college “in the forefront of higher education,” Mitchell addressed the Bates community Oct. 27 following the dedication ceremony for newly renovated Hedge and Roger Williams halls.

Bates President Nancy Cable introduced Mitchell with an impressive summation of the senator’s long career in public service.

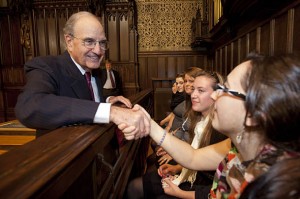

George Mitchell, whose Mitchell Institute provides scholarships to Maine students, greets Bates Mitchell Scholars on Oct. 27. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

“The United States is the first true meritocracy in human history,” Mitchell told about 200 people in the Chapel. But that meritocracy is broken if its benefits aren’t available to all Americans. “We have to make certain that we can draw on the talents of every member of our society,” and improving access to higher education is one way to do that. (In discussing the rising inaffordability of higher education, Mitchell’s speech anticipated the college-costs symposium scheduled for Saturday, Oct. 29.)

Mitchell pulled out statistics to support the common wisdom that more education means greater financial health. In Maine, he said, recent studies have indicated that people holding a bachelor’s degree earn 50 percent more than those who don’t. Similarly, those who stopped with a high school diploma are more than twice as likely to be unemployed than B.A. holders.

“We have a huge challenge in front of us,” he said, “but it’s also a huge opportunity, and it can provide a huge benefit to our state and our society,” meaning the higher tax revenues and lower government spending that come with higher rates of college graduation.

“It is a good investment to help young people go to college.”

Former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell answers questions following his “Open to the World” keynote address as Associate Professor of Politics John Baughman looks on. Photograph by Rene Minnis.

In a parallel to a story told during the dedication by Paul Marks ’83, Mitchell used his own example to illustrate the transformational role education can have. During a question-and-answer session that followed his address, he described growing up in Waterville, Maine, a son of a woman who was a Lebanese immigrant and a father of Irish extraction. A poor athlete among siblings highly accomplished in sports, Mitchell had poor self-esteem and was an indifferent student.

But a teacher at Waterville High School took Mitchell aside, gave him a book (John Steinbeck’s The Moon is Down) and told him to read it and give her an oral report on it. He read the book that night, she gave him another, and what followed was a literary year that turned Mitchell, a future federal judge, senator, peace-broker and author, into a reader. “My life would have been very different” without that teacher, he said.

Years later, as senator, Mitchell attended a University of Maine conference examining the aspirations of Maine’s young people. The message from the conference was that many young people in Maine, especially rural and low-income, had low aspirations.

Former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell speaks with a guest during a reception following Mitchell’s “Open to the World” keynote address.

After the conference, hoping to serve as a role model, Mitchell set himself the goal of visiting every Maine high school twice, once to speak at graduation and once to meet with students and teachers. “I saw in the eyes of many of those students a mirror image of myself at their age,” he said.

What grew out of that effort was the Mitchell Institute, founded in 1994. Based in Portland, the institute grants a Mitchell Scholarship to a graduating senior from every public high school in Maine who will attend a two-or four-year postsecondary degree program. Among the more than 1,800 Mitchell Scholars to date, 93 have attended Bates, Mitchell said.

The institute has an especially close connection to Bates, as Bates’ own William Hiss ’66, longtime admissions dean and now a development officer, was, Mitchell said, “the most influential person in advising how this program would be set up and implemented. “He was, and is, one of the most intelligent people I’ve ever met, in the field of education and beyond.”

(He was so impressed by Hiss that at one point, he asked Hiss to lead the institute. Hiss declined, but recommended someone else for the job — his wife, Colleen Quint ’86. A former Mitchell staffer in the Senate, she has been executive director since 1999.)

Mitchell has still another Bates connection in the late Edmund S. Muskie ’36, whom he described as “my mentor, my hero and ultimately my friend.” A former aide to Muskie during his long tenure in the U.S. Senate, Mitchell was later tapped to fill the Senate seat Muskie vacated when he became U.S. Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter.

Mitchell concluded his formal speech by describing the satisfaction he felt, from the perspective of an immigrant’s son, as a federal judge presiding over naturalization ceremonies. After the ceremonies, he used to ask the new Americans about their stories and why they wanted to be citizens. One young man, not yet a great English speaker, answered, “I came here because in America everybody has a chance.”

Mitchell said, “A young man who had been an American for 10 minutes, who could barely speak English, was able to sum up the meaning of being an American in a single sentence.”