In Museum of Art exhibition, Xie explores history, media, memory

The Bates College Museum of Art continues its leadership in bringing contemporary Chinese and Chinese American art to Maine and beyond with the exhibition Xiaoze Xie: Amplified Moments (1993-2008), opening Monday, Jan. 23.

A native of China and professor of art at Stanford University, Xie is a nationally known artist whose work explores cultural memory, time, and social and political manipulations of history.

“This exhibition is unique in that it is the first to look at 15 years of Xiaoze’s work, in all media, and important works from all of the major painting series,” says Bates museum director Dan Mills, who curated the exhibition while director of the Samek Gallery at Bucknell University.

Xie, who will be a learning associate at Bates this winter, discusses his work at 6 p.m. Thursday, Jan. 26, in Room 104 of the Olin Arts Center, 75 Russell St. The museum, also located in Olin, is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday.

All museum activities are open to the public at no cost. For more information, please contact 207-786-6158 or museum@bates.edu.

Showing at the museum through the same period is James Ensor: ‘Scènes de la vie du Christ’ and Other Works, including a portfolio of 32 lithographs by the influential Belgian artist.

Amplified Moments

“Xiaoze Xie wants to have it all in his art: He wants meaning as well as beauty, politics as well as humor, and realism as well as abstraction,” wrote Bob Keefer, a reviewer for the Register-Guard in Eugene, Ore., where Amplified Moments appears through December at the University of Oregon.

A U.S. resident since 1992, Xie was born in 1966, the year that began China’s devastating Cultural Revolution, and attended university in Beijing during the Tiananmen Square protests. If his work is informed by Chinese history, though, this exquisitely skilled artist is more concerned with factors that transcend ideology and nationality.

“What ties all [my] works together is the interest in time, in memory and in history,” Xie told an interviewer at the University of Oregon in November. “There’s always this sense of contemplating time, the passage of time and how changes in history and politics are documented.”

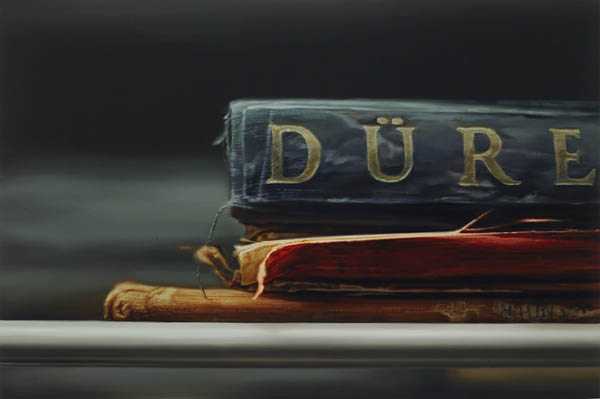

The documentary medium of photography, in particular, is central to Xie’s work — in both his adaptations, in paint or ink, of images from the news media, and his sumptuous renderings in paint of his own photographs of books and newspapers.

In fact, Xie is known particularly for paintings that show stacks of those publications stored in libraries and archives. Those paintings, art scholar Britta Erickson writes in the Amplified Moments catalog, capture a strange duality in human nature: We take the trouble to preserve these representations of the past, yet having preserved them, then largely neglect them.

For the viewer, Keefer wrote, “photographic devices such as narrow depth of field and motion blur, familiar to us from about a billion contemporary journalistic and advertising photographs, are translated into creamy brush strokes. The combination is extraordinary.”

Amplified Moments is also distinguished by Xie’s work in other media, such as ink drawings, videos and installations.

The 1999 installation “Order (The Red Guards)” refers explicitly to the Cultural Revolution. A painted scroll, reaching into the viewer’s floor space, depicts a library whose books have been mutilated and thrown around. A grid of metal squares, painted black and red — a combination frequently seen in Xie’s work — stands between the viewer and the scene of vandalism.

Like a hall of mirrors, Xie’s work invites a complex contemplation of the nature of history and memory, and how media representations both reflect and distort a past that we have in common yet experience alone.

Indeed, Xie himself resists simple responses to his work, as he said in a 2010 talk at Bucknell. “I don’t want to give up painting for installation or video; I don’t want to give up the figurative for the abstract; I don’t want to give up the political for the cultural; I don’t want to give up my Chinese-ness for the universal; I would never give up sincerity or beauty for irony.

“I want all of these in my work. For me, a good work of art should be able to generate complex layers of meaning.”

Mills, who is also an artist, first met Xie at Bucknell, where Xie taught before going to Stanford. The two had adjacent studios for eight years. “Dan is most knowledgeable about my working process,” Xie told the University of Oregon interviewer. “He knows about my hesitation, my worries, my struggle. So I’m so glad he put the show together for me.”

The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated 92-page catalog with essays by Erickson, Mills and art scholar Karen Smith, and is supported by a Freeman Foundation Grant.