Plastas book explores prejudice, progress in women’s activism between world wars

Her experiences working with a pioneering antiwar organization led author and Bates College professor Melinda Plastas into the research that has resulted in a recent book.

Melinda Plastas, visiting associate professor of women and gender studies. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

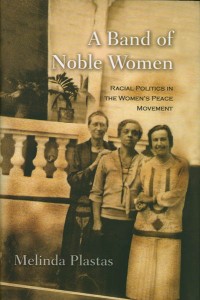

Offering new insights into the complex currents of racial politics between the world wars, A Band of Noble Women: Racial Politics in the Women’s Peace Movement (Syracuse University Press, 2011) is an engaging, surprising exploration of the convergence of two progressive forces: the women’s peace movement and the black women’s social reform and racial justice movement.

Plastas, visiting associate professor of women and gender studies at Bates, uses portraits of movement leaders and case histories of their work — such as a multi-year effort to pass federal anti-lynching legislation and a 1926 investigation of the U.S. occupation of Haiti — to illustrate the tangled difficulties of working for social change.

In the tumultuous years after World War I, white and black female advocates for peace and racial justice realized that ending war must also entail an end to institutionalized racism. “They were committed to a social justice approach that says, you can’t just look at one issue,” explains Plastas, who has taught at Bates since 2005. “You need to look at systems of power.”

Or, in the words of African American social reformer Addie Hutton, one of the leaders Plastas profiles, “There can be no world peace without right local relations.”

At the heart of Noble Women is the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), which between the world wars became a widely influential peace organization. Half a century after the events described in her book, Plastas herself worked for WILPF, first as an intern, later as an employee, rising to the rank of national program director.

That experience launched her toward the research represented in the book, Plastas’ first. “I hope the book will show that the way race works is really complex,” she says. “I tried to convey a sense of the different planes on which race was at work — the ways it shapes intellectual thought, domestic and international politics, who has access to which institutions.”

Even as white and black women began collaborating within WILPF, prejudice among some white leaders left black activists sidelined. In fact, black women in this early and formative phase of the long civil rights movement often found themselves doubly marginalized, as the black men leading a newly assertive civil rights movement also discounted their contributions and capabilities.

“They came from an era in which black women’s reform work was central to black resistance politics,” says Plastas. But after the war, “black masculinity became a symbol of resistance and white feminist internationalism became a symbol of resistance” — leaving black women “astutely aware of how the ground shifted between these two populations, populations that they wanted to be allies with.

“I was really compelled by that.”

The hopes and frustrations of black women like Hunton and Alice Dunbar-Nelson become clear as Plastas profiles them and four other leaders — in total, three white and three black. The profiles create telling contrasts among the motivations, resources and methods of such influential figures as Hunton and white racial justice advocate Emily Greene Balch, the second woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize (the first being WILPF founder Jane Addams).

The hopes and frustrations of black women like Hunton and Alice Dunbar-Nelson become clear as Plastas profiles them and four other leaders — in total, three white and three black. The profiles create telling contrasts among the motivations, resources and methods of such influential figures as Hunton and white racial justice advocate Emily Greene Balch, the second woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize (the first being WILPF founder Jane Addams).

For Plastas, researching the book was a way of comprehending the roots of a compelling life interest. As an undergraduate at Ohio Wesleyan University, she majored in political science and social welfare and minored in women’s studies. “As a budding young feminist, I was really interested in how race and racism functioned in women’s movements,” she says.

WILPF, still robust in the 1980s, gave Plastas hands-on involvement in social justice advocacy. “Not just in its mission statement, but through its actions on the ground, it was WILPF that really allowed me to understand how all these issues are connected.”

Her projects, reflecting progressive flashpoints of the time, included campaigns to end the arms race, South African apartheid and militarism in Central America. All the while, she says, “I was reading and discussing with WILPF members the writings of people like anti-racism and prison activist Angela Davis.”

Plastas adds, “The other thing that sparked my imagination and confidence was the fact that the WILPF leaders, primarily much older women, really listened to me, a young twenty-something.” One of those leaders, by then in her 90s, was Mildred Scott Olmstead, whose efforts to initiate interracial peace committees are described in Plastas’ book.

“She listened to me and cared about what I, and other young staff and volunteers, thought about contemporary politics and strategy.”