In NAACP project, students get fresh lesson in value of old papers

Students in the Short Term course "Making African American History: Preserving the Archives of the Portland NAACP" examine documents during a work session at the University of Southern Maine. From left: Joncarl Hersey '12, Tasheana Dukuly '12, professor Mollie Godfrey, Munroe Graham '13, Brad Reynolds '14. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

A placard inviting people to join the NAACP chapter in Portland, Maine.

A letter from NAACP leadership decrying the city government’s silence after a racially motivated assault in Portland.

A photograph of Coretta Scott King with U.S. Sens. Olympia Snowe and Hillary Clinton taken at the Portland chapter’s 40th anniversary celebration, in 2004.

These are among the papers of the NAACP’s branch in Portland, Maine — documents that, thanks to a two-year collaboration among the association, the University of Southern Maine and Bates, are being made accessible to researchers and the public for the first time.

The exhibition Making African American History: The Maine NAACP Collection, 1987-2012 shows through June 8 at the Glickman Library, sixth floor, University of Southern Maine, Portland campus.

Stored for years at the home and office of NAACP President Rachel Talbot Ross, the materials have been processed and arranged for archival storage by students in Bates Short Term courses in 2011 and 2012. While there is still work to be done with the materials, they now constitute the Maine NAACP Collection at the University of Southern Maine — whose Glickman Library, at the Portland campus, is showing highlights from the collection through June 8 in an exhibition curated by the Bates students.

Membership cards and informational materials from the Maine NAACP Collection, shown while Bates students were processing the documents for archival storage. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

The NAACP project was the brainchild of Mollie Godfrey, visiting assistant professor of English at Bates and an authority in African American literature and politics of the Jim Crow period. It was a collaborative effort involving not only Susie Bock, head of special collections at USM and director of the university’s Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine, but staff at Bates’ own Edmund S. Muskie Archives, who trained the students in working with archival materials.

They ended up going through 20 boxes of papers, photographs, videotapes and so forth documenting about two decades of NAACP activities in Maine’s largest city, starting in 1987.

Like the countless bits of ceramic that make up a mosaic, such materials are among the constituent parts of what we understand as history. And what story can someone draw from the Portland NAACP collection about the African American presence in Maine?

The biggest lesson, as Ross points out, may be simply that such a presence even exists. “A lot of the secondary sources Mollie had us read, before going to the archives at USM, were saying that African Americans don’t exist in Maine,” the whitest state in the union, says Munroe Graham ’13, a history and politics double major who was one of the nine students in Godfrey’s Short Term course this year.

“But you look at these materials and you see that there was huge attendance at these events held by the NAACP, or that there were protests and articles in the newspaper every day. It’s completely different from how people perceive African American history in Maine.” And now researchers will be better equipped to change that perception.

From the academic standpoint, the project gave the students an opportunity to satisfy the history faculty’s eternal cry of “primary sources!” Sam Wood ’12, a history major from Waterville, Maine, found himself relishing the opportunity to get his hands on the NAACP materials.

Jamilia Davis '15 and professor Mollie Godfrey look at a file of NAACP documents. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

“It’s a very different kind of research than, you know, what you’re most exposed to in college,” says Wood. “You feel like you’re actually discovering things, as opposed to being told what was discovered. It makes it just that much more fun and exciting.

“When you’re actually digging through the archives, you’re eager to find the next thing,” he says. “You’re trying to make sense of it and place it in context, and it’s a much more active process” — all the more so because of the detective work that’s part of piecing together a bigger picture from scraps of information.

“It poses a lot of challenges, because a lot of the time the context isn’t given, or these documents could be misfiled or you don’t know what these notes are referring to. So it’s difficult, but it requires more investigation and, I think, is much more rewarding and fun.”

“I think the students can see, more than they might have before, really how ambiguous and unshaped history is, and the kind of work that historians have to do to make sense of it,” says Godfrey.

“By the end of the course they were actually able to see a history just by arranging the material that they had not been able to see at the beginning.”

If raising awareness of Maine’s African American community is one goal of this archival project, another is to raise awareness, among that community, of the value of archival preservation.

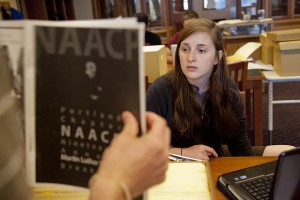

Munroe Graham '13, a member of the 2012 Short Term class "Making African American History: Preserving the Archives of the Portland NAACP," looks at an Martin Luther King Jr. Day event program during a work session at the University of Southern Maine. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

Ross is acutely cognizant of that worth: She’s a daughter of Gerald Talbot, Maine’s first African American legislator and the first president of the current Portland chapter of the NAACP. His papers constituted the first donation to the African American Collection of Maine at USM’s Sampson Center, to which the Maine NAACP Collection also belongs. (A pioneer of civil rights in Maine, Jean Byers Sampson was married to longtime Bates math professor Richard Sampson.)

And Ross knows that, as so often happens with members of grassroots organizations, many NAACP people in Maine have — as she did until recently — valuable documents sitting in their houses gathering dust.

“We want them to understand that their contribution is so meaningful,” she says. “If they donate these materials, we can acknowledge that, and it’s for the betterment of the organization and then the public.

“To have your history be visible, particularly African American history, civil rights history in Maine, that has a real value,” she adds. “This feels like a rarity, and it feels like an amazing statement.”