On a Sunday afternoon in December, the Clifton Daggett Gray Athletic Building had become a bustling event venue, as Bates leaders sat onstage before hundreds of students, faculty and staff who had put aside studies, holiday errands and football games to meet their next president. Clayton Spencer was backstage, listening for her name — her cue to come forward.

Interim President Nancy Cable welcomed the throng, followed by Presidential Search Committee co-chair Michael Chu ’80.

And when trustee chair Mike Bonney ’80 wound up his introduction with the simple words, “Welcome, Clayton Spencer,” she stepped from behind the curtain, smiling, grasping the pages of her speech and ready to greet a crowd eager to know more. A little choked up, she began a new relationship with her new college.

She surveyed the gathering and spoke her first word as president-elect of Bates College. “Wow!”

From her formative upbringing as the daughter of a college president to her innovative policy work at Harvard, Clayton Spencer’s rise as a U.S. higher education leader culminates in her wow debut as president-elect of Bates — and her avowed commitment to leading Bates toward a stronger marriage of excellence and opportunity.

Made for the job

Ava Clayton Spencer was born in December 1954 to Samuel and Ava Spencer in Concord, N.C.

“I grew up as the daughter of a college president. I used to sneak across campus to watch commencements as a kid,” she recalls. “Dinner conversation was about the issues facing the college.”

Previously president of Mary Baldwin College, Sam Spencer began his 15-year tenure as president of Davidson College in 1968. By then, those dinnertime topics included the Vietnam War, civil rights, coeducation (Davidson was still all male) and fraternities.

That wasn’t all: in the city of Charlotte and surrounding Mecklenburg County, the landmark busing case Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education was heading to the Supreme Court.

“Because we were in a small town in North Carolina, guests of the college would stay with us or have a meal. I was a teenager by then, and I’d gone from listening to the adults from a window seat in the living room, to wanting a seat at the table and attending the various talks and lectures at the college. I soaked up everything.”

Fatherly advice

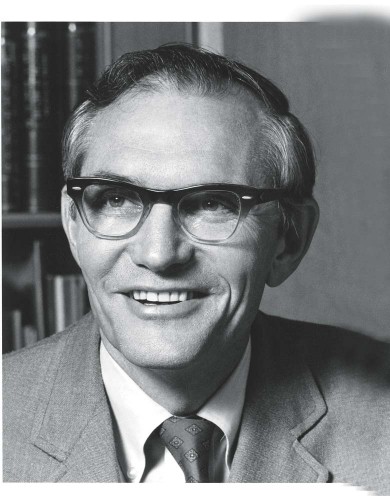

“What I learned from my father,” Clayton Spencer says, “and what I’ve learned and relearned throughout life, is that whatever you’re doing, you have to be authentically you.” Samuel Reid Spencer Jr. served as president of Davidson College, his alma mater, from 1968 to 1983.

The road to the presidency

Spencer studied history and German at Williams College, making her the second Bates president to have a bachelor’s from there, after T. Hedley Reynolds, Williams ’42. She then read theology at Oxford University and earned a master’s in the study of religion at Harvard.

She is the first to have a law degree, from Yale.

Of her decision to not seek a doctorate in religion, she says that she “wanted a life that combined ideas and action, and therefore landed at Yale for law school. I was able to do the kind of conceptual thinking I love, while staying engaged in the facts on the ground. That dialectic, between ideas and facts on the ground, has informed my life ever since.”

Power from dialectical poles

“The field of religion fundamentally deals intellectually and morally with contradictions. How do you stay optimistic when you know that you’re going to die, when you know that bad things are going to happen to good people?

“Religion takes on these contradictions, placing you between the poles of the contradiction and making you think dynamically about finding a way forward. Dialectical thinking is how I move through practical problems. It’s the furniture of my mind.”

A lesson from Ted Kennedy

Speaking of “poles of contradiction,” Spencer tells a story about working on Capitol Hill for the late U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy, as chief education counsel to the U.S. Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, which Kennedy chaired.

“I first met the senator when we were trying to pass direct lending for student loans, moving from a guarantee-agency system to funding directly from the federal government to colleges. I wrote a memo about how we were going to move 100 percent to direct lending in one fell swoop.

“I was called in to meet with the senator. He sat in his well-worn leather armchair. And he said, ‘Clayton, I’ve read your memo. It’s a really smart memo. Why don’t you take a walk with me down the hall?’

“He took me to the office of Jim Jeffords, then a Republican senator from Vermont before he went independent. Jeffords was the swing vote on the committee. He said, ‘Jim, my new education staffer here thinks this direct-lending thing is going to go through, no problem, at the markup next week. Can you tell her how many votes you have on the Republican side?’

“Jeffords said, ‘Well, Ted, I’ve got one or two on my side, but you ought to be more worried about your side. You don’t have a majority of the Democrats yet.’

“The senator walked me back, and he said, ‘We’ll give it several weeks, we’ll work it and then we’ll get this done.’ That was how I was introduced to getting things done on Capitol Hill: It takes more than smart memos to win the day.”

The ideal persuader

“The Senate is a culture of persuasion, as is a college campus,” Spencer says.

“Sen. Kennedy cared passionately about ideals, but he knew that ideals were sterile unless you could somehow put them into action. He was one of the most productive legislators in U.S. history because he knew when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em.”

Given Kennedy’s stature and power, Spencer, in effect, was chief education counsel for not just the committee but “the entire Senate and the country,” says Nick Littlefield, former Kennedy chief of staff.

“Clayton was a leader. She could master the substance of any issue; she could build the bipartisan alliances to get the initiative passed; and she could communicate the objective and details of the initiative in a charismatically persuasive way.

“She was one of the most respected staff directors I’ve ever known.”

Getting things done

Spencer joined Harvard in February 1997 as a consultant for federal policy issues. The following year, she was appointed associate vice president for higher education policy reporting to the President, and in 2005 she rose to the new position of vice president for policy.

Working directly with four different Harvard presidents, Spencer became known for her collaborative approach, effectiveness in getting things done and passionate commitment to access and affordability.

Of her involvement in various university-wide initiatives, from a task force on the advancement and support of women in academic life to the role of the arts and international strategy, Spencer is especially proud of her part in three projects at Harvard:

• The merger of Harvard and Radcliffe College and the subsequent transformation of Radcliffe into an institute for advanced study;

• The redesign and dramatic expansion of Harvard’s financial aid program;

• The creation of the Crimson Summer Academy for academically talented high school students from financially disadvantaged backgrounds.

“I learned a great deal by observing a variety of leadership styles,” she says. “The most basic lesson is this: Effective leadership is based on persuasion, not on hierarchy or on one’s position on an organizational chart. Leadership is most effective when you bring cooperative work to bear on solving hard problems.

(Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I believe this is one of the most fun things to do in life. You take on a hard problem, get the best thinkers around the table, invite the great ideas and then move toward actual, concrete outcomes. In my experience, achieving a unity of ideas and action will motivate the entire community and propel an institution forward.”

Turning crimson

Her highly effective yet low-key style caught the attention of The Harvard Crimson, which in 2008 published a profile headlined “Right-Hand Woman.”

“…[C]olleagues say she studiously avoids imperiousness,” wrote Clifford Marks, now a reporter for the National Journal. “Fellow trustees of Williams College, on whose board she has served for five years, say that Spencer is an exceedingly modest ‘coalition-builder,’ experienced in organizing support in the ego-dominated halls of both Washington and Cambridge. ‘It’s not Clayton’s style to hold herself out as “I know more than you do,”’ said Williams trustee Michael Keating. ‘She’s very careful to say, “Based on what I know, I have this point of view.”’”

The Gomes connection

Spencer says she was “very privileged” to work at Harvard with the late Rev. Peter Gomes ’65 in his role as the Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church.

“Peter had such rich and contradictory gifts, and you saw them all in a dynamic blend that was enormously powerful.

“I was introduced to Bates in part through Peter’s love for the college. Peter wrote in one of his later books, The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus, that Jesus ‘wants us to live in the full implications of our human gifts.’ That’s a pretty interesting way to encapsulate the essence of the liberal arts, and the Bates experience as well.

“Clearly that’s a lesson he took very seriously and deeply.”

Coming to the party

“In the course catalog, you describe yourselves as a community of people who love ‘ideas, artistic expression, good talk and great books.’ Who wouldn’t want to be at that party?

(Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“When I read the presidential prospectus, I was blown away by Bates. It was love at first sight. Any college that leads its mission statement with an affirmation of the ‘emancipating potential of the liberal arts’ is a place I want to be.

“Then there’s the fact that from your earliest beginnings, Bates welcomed women and African Americans into the full standing of the scholarly community, at a time when that simply wasn’t done. I love a place that does what is right, rather than what is expected.

“Another quality that comes through loud and clear is the lack of pretension, that sense of being down to earth, having an authentic way of moving through the world. And that suits me to a T.”

Adding to the allure is the college’s place in the state of Maine and the city of Lewiston. “I find this state fascinating and I respect its reserve — the fact that it’s hard to crack.”

What’s fun?

“Movies — all kinds. Solving hard problems with smart people. Basketball. Arugula salads. Being a mom [daughter Ava Carter is a Harvard junior; son Will Carter is working on Wall Street with a degree from NYU]. Good friends. Catching up with James Reese, a 10th-grade classmate!”

Not what we have, but what we do

“One of the legacies of the 2008 financial crisis is that we can no longer, in our society, equate wealth with excellence in higher education. But Bates knew that long ago: Bates was founded on the idea that it’s less about what we have and much more about what we do. That is tremendously appealing to me.

“The important thing for us now is to make sure that Bates is delivering on the liberal arts model as much as we say we are, and to make sure that the value added in this experience is worth the price.”

Win, at some cost

“I am simple-minded. My view is that in athletics, as in everything else, it’s not worth doing unless you do it with the same commitment to rigor and excellence that you apply in other fields.”

Take cake, forget humble pie

“I know Bates is famous for being humble, but I hope now that the college can step up and claim its excellence and rigor. Bates is doing important work in shaping a direction for the liberal arts in this new century. You see it in the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, in the general education curriculum, and in the ongoing commitment both to individual and collaborative work for theses and capstone projects.

“To my mind, Bates is poised to be a leader in transforming the liberal arts for today’s world.”

(Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Knowledge and wisdom

“Given the welter of information and stimuli that confront people today, it is important to give students a framework of values and knowledge that can lead to wisdom that will guide them in life.”

Obligation to democracy

“Education is the key to the American dream. Ideally, it provides individual opportunity to talented students, whatever their backgrounds, and creates the educated citizenry that is essential to a healthy democracy and civil society. Unless higher education marries excellence and opportunity, it is not doing its job. It’s an old-fashioned idea, but it’s never been more important than it is today.”

Passion and tools

“I think we need the courage of our convictions about the liberal arts experience. It’s not the right option for everyone, but at its best, it teaches young people to harmonize their passions with rigorous intellectual training and to take a sense of creativity and possibility out into the world to serve purposes larger than themselves.”