Party platforms reflect ideological battles, says political scientist Engel

Engel is a widely published expert on American party politics who coauthored the 2007 paper “Do Words Matter? Party Platforms and Ideological Change in Republican Politics.”

Conventional wisdom says that today’s candidate-driven campaigns make party platforms slightly more relevant than last week’s grocery store circular. In 1996, for example, then-presidential candidate Bob Dole famously admitted to not reading the Republican platform.

But as Engel tells Suzy Khimm, a contributor to the Wonkblog at The Washington Post, a platform is an opportunity for “the party base to assert its principles, figure out what its principles are, to show its own strength in the party.”

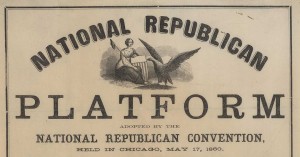

The 1860 Republican Party platform called the expansion of slavery a “crime against humanity.” Detail of a photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana.

In their paper, Engel and coauthor Julia Azari further argue that tracking changes in a party’s platform over time can explain a woefully under-studied aspect of party politics: how factional battles affect party ideology.

The paper notes that between 1976 and 1980, the Republican Party platform became more conservative. Support for the Equal Rights Amendment ended, and the platform moved to the right on abortion, among other changes.

That shift, Engel and Azari conclude, meant that “that certain ideological groups…prevailed over others within the party.”

In addition, the new platform sent a signal to certain interest groups that they could expect policy commitments from the party, say Engel and Azari. The two scholars also found that platform language and ideology were later used to “fuse the socially conservative agenda with other aspects of the conservative Republican agenda.”

In retrospect, Engel tells The Washington Post, the 1980 Republican platform was a key “document of the ideological change of the party.”