Hospital reveals inside story as physics students explore medical imaging

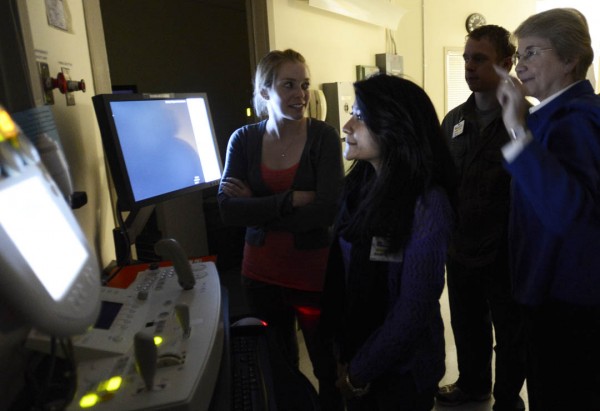

Donna Knightly, manager of radiology at St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center, demonstrates an X-ray machine for physics students Samantha Forrest ’13, Raisa Sharmin ’13 and Keyan Riddell ’16. Photograph by Mike Bradley/Bates College.

Even an untrained eye could see that there was a problem with the human spine depicted in shades of gray on a computer screen: One of the vertebrae was smaller, darker and denser than the others. It was a compression fracture, a painful collapse of the disk.

In a room deep within St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center, just blocks from campus, four Bates students paid close attention to the screen image created by a magnetic resonance imaging scanner, and to the two technologists discussing it.

As the students looked on, technologists Barbara Mandy and Brian Laudieri were taking diagnostic images of the injury suffered by an elderly woman. She was being scanned in the adjacent room. Slight and frail, she lay motionless in the “tunnel” of an MRI machine. Only her feet, clad in white socks and with blankets tucked around them, were visible.

The Bates students were at St. Mary’s on assignment for a physics course. Taught by Michael Durst, a visiting assistant professor, the course Optics of Life took a dynamic, hands-on approach to introducing the students to biomedical imaging technology, from microscopes to MRI.

Visiting Assistant Professor of Physics Michael Durst talks to his Optics of Life class. Photograph by Michael Bradley/Bates College.

Durst’s 23 students made the short trek up Campus Avenue in November to see the hospital’s imaging facilities during hour-long, small-group tours that he arranged with radiology manager Donna Knightly. The arrangement was typical of the long and fruitful partnership that the college and hospital enjoy. “We dance together as only old friends and neighbors can,” says Knightly.

In addition to the MRI, the students saw demonstrations of ultrasound, with one student even serving as a subject for an ultrasound scan of her kidney, and conventional and computed tomography X-rays.

The visits gave life to the concepts discussed in class, says Samantha Forrest, a senior neuroscience major from Bozeman, Mont. “Things stick with you more when you can see them actually performed,” she explains. “I liked being able to talk with the technologists. That’s a viewpoint that you can’t really get from a book.”

“Seeing how the machines were used was really interesting,” adds Phi Nguyen, a senior neuroscience major from Methuen, Mass. “Watching how patients were scanned, and the resulting pictures, showed us how the machines worked on a practical level.”

The St. Mary’s visits were part of a course curriculum designed, in part, to attract students to physics, a common goal for 100-level courses in that discipline at Bates. Durst unveiled the science behind technologies that nearly everyone is aware of and that have clear career implications. It was also explicitly interdisciplinary.

Ultrasound technologist Jared Theberge demonstrates the scanner for Raisa Sharmin ’13 and Keyan Riddell ’16 during a tour of imaging facilities at St. Mary’s Hospital on Nov. 27. Photograph by Michael Bradley/Bates College.

“The idea was that any student at Bates could take this course, regardless of background, and be able to get up to speed and keep up,” says Durst.

Durst’s inspiration for Optics of Life was his own research into 3-D biomedical imaging that uses optical sectioning, a kind of laser microscopy that can literally see through the surface of tissue without making an incision. About two-thirds of the course was devoted to optics.

Durst reached out across campus and into the community for guests who could make lively and engaging presentations to the class. In addition to the hospital, contributors included:

- Will Ash of Bates’ Imaging and Computing Center, who demonstrated different microscopes;

- Glen Ernstrom, a visiting professor of biology, who discussed his research with worms genetically modified so that their neurons glow when stimulated by certain wavelengths of light;

- and Lewiston firefighters who demonstrated infrared imaging gear that enables them, in effect, to see through thick smoke.

The presentations “made for a really engaging class,” says Forrest.

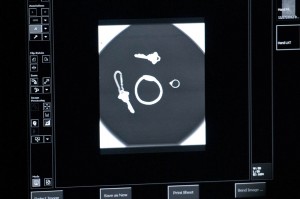

St. Mary’s radiology manager Donna Knightly shot this X-ray of a few items worn or carried by the Bates students. Photograph by Michael Bradley/Bates College.

But serious science lay at the heart of the course. MRI scanning, for example, uses magnetism and radio-frequency waves to trick the atoms in living cells into emitting signals that can produce an image.

“You could teach all of physics through this course,” says Durst. “You start to realize why pre-med students have to take physics, and why it’s on the Medical College Admission Test.”

“Students are still figuring out what they want to do career-wise. They can see that there’s a point in learning all this. It’s not just purely academic.”

The class was evenly divided by gender, represented all four class years. Bearing out Durst’s hopes, it attracted majors from both within the physical sciences and outside — two in economics and one each in French and in classical and medieval studies.

“My goal in wanting to teach at Bates in the first place,” he says, “was that students here take courses outside of their major, outside of their comfort zone.”