Chapel to Lewiston: Hello!

After Harvard Yard was closed to the public during the 2011 Occupy Harvard movement, a graduate student complained that “we don’t want our university to be a gated community.”

Yet the traditional college quadrangle resembles exactly that. Enclosed on four sides, a quad’s buildings face inward and there are gates galore. “And when you create a ceremonial portal like a gate, you’re telling visitors that they are entering another world,” says Philip Isaacson ’47, architectural critic and author.

Bates, however, adopted a different model, placing its first two buildings, Hathorn Hall and Parker Hall, side by side atop a sloping plot of land in 1857. Bold and simple, the arrangement was considered “very distinguished,” Isaacson says. Still, early Bates leaders “hadn’t made up their mind how they would handle future buildings.”

Which brings us to the intriguing decision, a century ago, about where the college would place its new chapel.

When Bates created its Chapel, now named for Peter Gomes ’65, the college trustees voted that the space in front of the Chapel would remain open and free from any other structure in perpetuity, “unless it be a monument, shaft, arch or similar construction.”

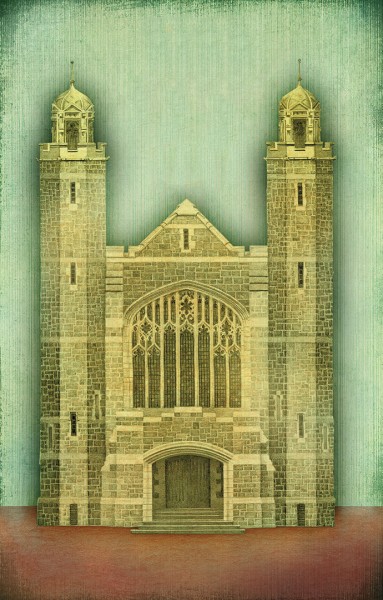

Dedicated in 1914, the Chapel is now named in memory of Peter J. Gomes ’65, the influential and beloved preacher, minister, professor and author.

The naming was celebrated at a service in the Chapel on Oct. 25, a day before the installation of Clayton Spencer as president. Among the speakers was Carl Benton Straub, professor emeritus of religion and the Clark A. Griffith Professor Emeritus of Environmental Studies, who began his reflection with the sentence that Keats asked be chiseled on his tombstone: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

With the naming of the Chapel, Straub said, Gomes’ name is now written in stone. Specifically, the stone is seam-faced granite, quarried a century ago near Hingham, Mass., and carrying a distinctive and natural tone and texture. “The walls which frame us, the turrets which anchor our conclave…give place for our remembering and for Peter’s name,” Straub said.

With its founding in 1855, the founders of Bates registered their protest against “castes, classes and social tyrannies,” in the words of George Colby Chase, the college’s second president. Befitting this iconoclasm, our own Historic Quad evolved less like the quads at places like Harvard, Bowdoin or Dartmouth. The layout is more open, like a city park, Isaacson suggests.

The chapel’s location is less an ecumenical gesture and more a “nod to the openness of the college to the community.”

As Oren Cheney’s chief lieutenant and then as president, Chase was, for many years, under chronic pressure to raise money for the latest college needs. By around 1910, money from Andrew Carnegie for a new science hall was in hand, so Chase was trying to raise money for a new chapel and new gym.

In January 1911, the pressure on Chase ramped up after the college received a $1,000 challenge gift that required Bates to raise another $3,000 — in three days — or forfeit the original $1,000.

So Chase, as he’d done many times before, took the train to New York City to meet with prospective donors. By his third day, he’d raised just $2,000. Two hours before his train was to leave, he received a message at his hotel inviting him to call on a donor — within 15 minutes.

He made the visit, secured $5,000 to meet and exceed the challenge, and then received another $60,000 a year later from the same donor, later revealed to be Ellen S. James, widow of industrialist and philanthropist Daniel Willis James.

“So, what’s the guy going to do?”

By the time money was in hand for the chapel, the east side of the Quad was filled with Coram Library (1902) and the forthcoming Carnegie Science (1913). So a location on College Street was selected. A likely challenge, Isaacson says, was how to orient the new building in that spot.

“So along comes Chase with a chapel,” muses Isaacson. “If he tries to have it face inward toward the park, its length is going to obscure Parker Hall. If you have it face Parker, then its back end is going to face the town, which isn’t going to look good, either. So, what’s the guy going to do?”

The solution was to place the Chapel parallel to College Street, with its porch facing Campus Avenue and the city of Lewiston beyond.

That this orientation has worked so well can be explained by Straub, who did research about the Chapel in the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library over the summer, both for his remarks at the service and for an historical essay published in a brochure about the Chapel.

Straub found that in June 1912, months before the laying of the cornerstone that November, the Board of Trustees voted to keep the space in front of their future Chapel open and free from any other structure, “unless it be a monument, shaft, arch or similar construction,” in perpetuity.

The decision acknowledged the simple fact that where buildings aren’t is as significant as where they are; in practice, it ensured that anyone coming up College Street from the city of Lewiston would have an unobstructed view of the Chapel.

Long ago, the college decided that no building would occupy space in front of the Gomes Chapel.

For Bates, a welcoming approach to the college was important. Barely a half-century old by then, Bates was still well-aware that it owed its existence to Lewiston’s industrialists — including namesake Benjamin Bates — the leading citizens who had donated the land for Oren Cheney’s new college back in 1855. Blocking the approach from town with buildings would be like “saying to the city, ‘Keep out,’” Isaacson says.

That the Chapel is the college building that welcomes town to gown is less a religious and ecumenical gesture, Straub says, and more a “nod to the openness of the college to the community, an acknowledgment of interdependence and of appropriate appreciation.”

At the Chapel dedication in 1914, architect J. Randolph Coolidge noted the importance of allowing the Chapel to say something graceful to the Lewiston community. “With [the Chapel’s] setting of over-arching trees, its wide porches, its easy approaches, it extends an invitation and a welcome to the college and to the city.”

That invitation still stands today. The Gomes Chapel is as “distinctive and impressive it was when it was built,” Isaacson says, and still does a splendid job of tying the college to its larger community and its original roots.

A century ago, he adds, “Bates College did the right thing.”

More about the Chapel

The recently published brochure Peter J. Gomes Chapel: Common Ground for Uncommon Pursuits, written by Carl Benton Straub, professor emeritus of religion and Clark A. Griffith Professor Emeritus of Environmental Studies, offers historical and contemporary perspectives on the Chapel and its role in the cultural and religious life of the college.

For a copy, please contact the Bates College Multifaith Chaplaincy at 163 Wood St., Lewiston ME 04240, or email lthomps2@bates.edu.