Spencer’s inaugural address: where Bates stands, how the college can move forward, while staying true to itself

Spencer to Bates: ENGAGE!

By Doug Hubley

Mace bearer Sawyer Sylvester, professor of sociology, leads the academic procession to Merrill Gymnasium on Oct. 26, 2012. Photograph by Mike Bradley

In the year since Clayton Spencer was named Bates’ eighth president, she has offered a strikingly active and consistent interpretation of where Bates stands and how the college can move forward while staying true to its own best self.

Her views have come at three signature addresses: the December 2011 event that introduced her to campus; during Reunion 2012 on the eve of her official start as president; and, most recently, at her Oct. 26 inaugural installation.

At each turn, Spencer has vividly described a specific scenario: As shifting economics and, especially, exploding information technology transform higher education as we know it, Bates can respond by being brighter and bolder about what it has always done so well — namely, standing firmly on principle while engaging robustly with the world.

In the next decades, “success will go to the institutions that engage most robustly and effectively with the forces that are reshaping our world.”

Fittingly, the inaugural address, titled Questions Worth Asking, was the richest statement of Spencer’s thesis to date, and she used Benjamin E. Mays ’20, the great educator, theologian and civil rights leader, as both a metaphor for the founding Bates ethos and a guide for applying that ethos to the coming times. (Take a new look at Mays on page 24.) Bucking societal norms, Bates was inclusive and progressive in ways that directly benefited students of color like Mays, a leader who in turn amplified and passed those values forward to lift up all of U.S. society.

His story, Spencer stated, makes clear that we have always “encountered individuals in their full humanity. We took as our task educating them with intellectual rigor, ethical responsibility and care for their fellow human beings.”

She added, “These qualities are in the DNA of Bates College, and they define us to this day. They also point the way forward.”

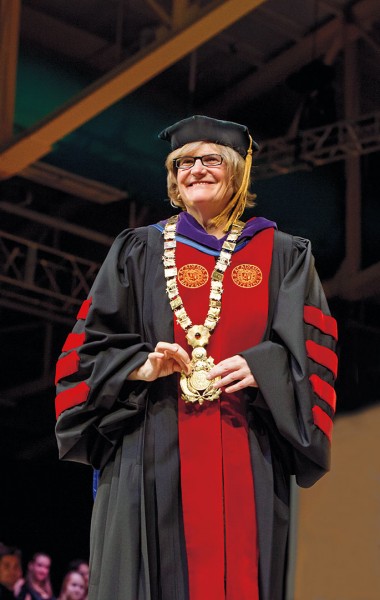

Clayton Spencer shows off the presidential collar following her installation as the college’s eighth president. Photograph by Mike Bradley

Spencer explored the theme of technology-driven change with the words of another new president. In his September inaugural address, MIT’s Rafael Reif situated higher education on the threshold of a “technological transformation [that] has the potential to reshape the education landscape — and to challenge our very existence.”

Unhindered access to unimaginable amounts of information has changed both the work of education — “some of the most powerful changes are occurring at the heart of scholarship and knowledge creation,” as Spencer pointed out — and the context in which it’s done.

So in their intellectual reach, liberal arts colleges like Bates “have become a great deal larger,” she explained. “Yet enlarging the screen on which we must project our institutional identity and compete for faculty and students makes this tiny campus…look ever smaller.”

In fact, liberal arts colleges educate fewer than 4 percent of the college students in America. And the relevance of the “tough-minded tradition of the small New England college,” as Thomas Hedley Reynolds put it at his own inauguration, in 1967, is increasingly questioned. But schools like Bates should regard such questioning as an invitation not just to demonstrate their relevance, but to strengthen it, Spencer said.

This scrutiny “challenges us to make a virtue of our scale, delivering our particular model of education at a high standard of excellence,” she said, describing a paradoxical liberal arts model that embraces both “the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, with no practical aim,” and the “teaching of values…that shape a human being who can in turn shape the world.”

Which brought her listeners back to a Bates graduate who had done just that: Mays, who remains the proof and embodiment of values that endure after 158 years, she said.

The Mays story, she said, is a story about mindset. For Bates, that mindset is about “standing firmly on principle and encountering the world with energy and confidence.” In the next decades, she said, “success will go to the institutions that engage most robustly and effectively with the forces that are reshaping our world.”

For Bates, this could mean changes in faculty recruitment, departmental structure, even how academic disciplines are defined — but most important, it means an even greater dedication to the goal of teaching and learning that engages with the world.

“We stand ready — together — to challenge ourselves and to engage the world.”

The mindset exemplified by the Mays story is one “grounded in ideas and values, but porous to the world,” she said. “For the liberal arts college it means, among other things, recognizing that the line between theory and practice is breaking down. It means…that we see the growing concern of students and parents with employment prospects… as a deep aspect of our obligation as a liberal arts college to prepare our students for a life of purposeful work.”

In her discussion of the character of Bates graduates, she took a cue from the late Rev. Peter Gomes ’65, for whom the College Chapel had been ceremonially named the day before Spencer’s installation. Liberal arts colleges, Gomes once preached, put “the making of a better person ahead of the making of a brighter person, or a better mousetrap.”

A poignant moment during the installation: Clayton Spencer hoists her academic cap, the same one that her father, Samuel Reid Spencer Jr., now 93, wore as president of Mary Baldwin College and Davidson College. Photograph by Mike Bradley

In Spencer’s words, the liberal arts college, with its intimate scale, has an advantage when it comes to this task of creating better people. Bates shapes human beings who are not only “equipped to navigate a complex world, but also motivated with empathy toward their fellow human beings,” a goal that comes alive every day through the legions of students exercising both minds and hearts through community-based learning projects in Lewiston.

And, through Mays, Spencer concluded her address by interpreting the notion of community as it has been constructed at Bates, one defined by openness and inclusiveness “well before we had the language for such things,” she said, adding that ours is an intentional community that anticipated, by nearly a century, the GI Bill that introduced a new egalitarianism to other campuses nationwide.

“The genius of American higher education is that it unites excellence and opportunity,” she said. Bates can claim this union “as a core element of our identity, and we need to continue to build on this deep aspect of who we are.”

Meaning, in practical terms, that Bates must make an “unwavering commitment” not only to the financial aid that supports a diverse student body, but to the existence of a campus culture “that embraces diversity across many dimensions, giving richness and power to the educational experience of all of our students.”

No one can predict the future, but Spencer closed her speech by invoking someone famed for predicting what its gadgets should look like: Steve Jobs. The late Apple co-founder once told a group of graduating students that “your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life.”

“Likewise, at Bates, we don’t have time to waste,” Spencer said. “But we are not in danger of living someone else’s life. We know who we are and what we stand for, and we stand ready — together — to challenge ourselves and to engage the world.”

Spencer’s inaugural address bates.edu/inauguration