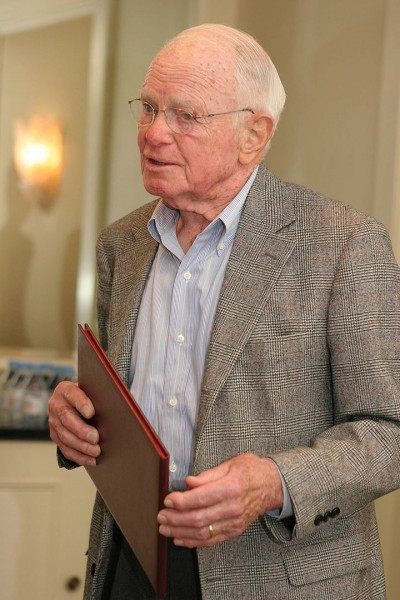

Trustee Chair Emeritus E. Robert Kinney ’39, corporate and civic leader with ‘good, gutsy Maine business sense,’ dies at 96

E. Robert Kinney ’39, LL.D. ’85, who entered the food industry by canning crabmeat in his Maine home en route to becoming CEO of General Mills, died May 2 in Arizona. He was 96.

Kinney, a Bates trustee for 27 years, including 17 as chair, was considered a creative entrepreneur and model corporate leader who, when appointed CEO of General Mills in 1973, was praised for his “good, gutsy Maine business sense” by his predecessor.

As a corporate leader, he said that he took the advice of a business mentor back in Bar Harbor, Maine, by throwing himself into service to the nonprofit world, especially to Bates.

As Kinney received a Bates honorary Doctor of Laws degree in 1985, then-President Hedley Reynolds lauded him for being “always thoughtful for the needs of others, always ready to serve, always ready with a helping hand.”

Born in Burnham, Maine, and raised in Pittsfield, Kinney was a Phi Beta Kappa graduate who earned money for college by working and living in the home of Lewiston mill industrialist Scott Libbey Sr.

Kinney received $500 in scholarships from Bates. At the time of his death, he was the college’s most generous living donor.

He also received about $500 in scholarship support from Bates, prompting Kinney to tell Dean of the College Harry Rowe, at graduation, that “I don’t know how I’m going to do it, but I’ll try to pay you back the scholarship money.”

At the time of his death, he was the college’s most generous living donor.

In 1942 while doing a Works Projects Administration study along the Maine coast, Kinney approached Matthew Highlands, a legendary University of Maine food scientist, with a crab question. Crabs could be had for a penny each — lobstermen were just tossing them from their traps — so could anything be done with them?

“You can cook them, process them and put them in hermetically sealed cans,” Highlands said. With World War II interrupting the supply of crab meat from Japan, the demand was rising.

Kinney learned the business at home, a few cans at a time. By the 1950s his North Atlantic Packing Co. was a $2 million-a-year business selling canned crab and other products and employing 400 in Bar Harbor.

Kinney then joined Gorton’s. For a society more and more eager for convenience, Kinney again used emerging food technology to lead Gorton’s to expand its frozen, ready-to-cook fish products, including the iconic fish stick and, by the 1960s, the fish for McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish.

Under Kinney, Gorton’s earnings went from $122,000 on sales of $12.1 million in 1958 to $1.44 million on sales of $71.9 million in 1968.

In 1973, he took the helm of General Mills, which had acquired Gorton’s in 1968. He served as CEO of IDS Mutual Fund Group in the 1980s.

A “compelling example that commitment to the common weal is the indelible mark of liberal learning.”

At Commencement 1985, when he received an honorary Doctor of Letters degree from Bates, then-Dean of the College Carl Benton Straub praised Kinney for “his compelling example that commitment to the common weal is the indelible mark of liberal learning.”

In 2008, Kinney received the college’s Benjamin Elijah Mays Medal, awarded for distinguished service to Bates and the larger community worldwide, and in 2005 he was a charter inductee into the Benjamin Bates Society, an honor accorded the college’s leading philanthropists.

Kinney provided major support for Pettengill Hall (1999), was instrumental in securing foundation grant funding for the Olin Arts Center (1986) and established an endowed professorship in history and a scholarship fund.

In Minnesota, Kinney served as a director of the Minnesota Symphony, the Guthrie Theater and the YMCA, among many others.

The commitment that I’ve had, emotionally and monetarily, was focused on Bates.”

Elsewhere in Maine, his support and service went many nonprofits, including the Bangor Theological Seminary, Maine Central Institute, Friends of Acadia National Park and The Jackson Laboratory. His Maine corporate board service included Hannaford Bros. Co., IDEXX Laboratories and Unum.

When Kinney offered his oral history to Bates’ Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library in 2005, he explained how a business mentor in Bar Harbor, a banker, encouraged him to make one or two meaningful commitments to organizations outside of business.

“The commitment that I’ve had, emotionally and monetarily, was focused on Bates,” Kinney said.

Kinney is also credited with significant reform of the Bates Board of Trustees in the 1980s when he introduced a resolution that mandated trustee retirement at age 70.

As he said in his oral history, “As smart as some people are when they’re 75 or 80 or whatever they may be…on the average you’ve got to have younger people. They stimulate the thinking…you want to renew, you need new blood.”

With support from the late U.S. Sen. Edmund Muskie ’36, among other trustees, the resolution was approved.

“Youth will keep the organization healthy,” said Kinney, who backed up that idea by mentoring at least two generations of young business leaders in Maine.

Kinney is survived by his wife, Margaret (Margee) Kinney; daughters Jeanie Small and Isabella Keating; stepdaughter Lucy Thatcher Penfield; stepson Ford Thatcher; seven grandchildren, including Samantha Kinney Leone ’93; two step- grandchildren; 10 great-grandchildren; and his sister, Elizabeth Kinney Jones ’44. He was predeceased by his son, E. Robert Kinney Jr. ’70, who is survived by his widow, Sally Greenlaw Kinney ’69.

His memorial service is at 4 p.m. on Friday May 17 at Plymouth Congregational Church in Minneapolis.