Five things everyone should know about the fearless, pioneering journalist William Worthy ’42

William Worthy ’42 who died May 4 in Brewster, Mass., at age 92, was, in the words of The Washington Post, a “defiant journalist” whose reports from communist countries during the Cold War drew the ire of the U.S. government and inspired a folk song.

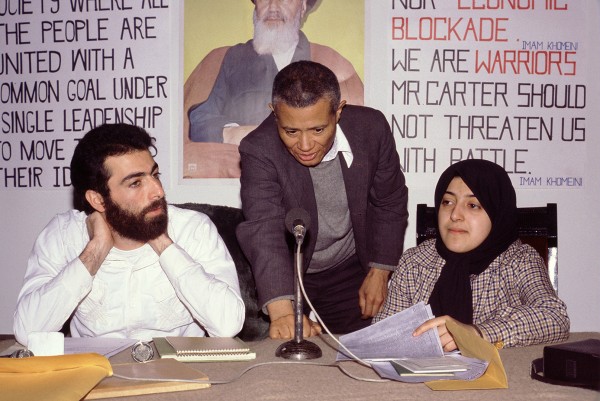

Worthy is shown here in 1980 setting up a press conference at a Tehran hotel with spokespeople for the students who held 52 U.S. diplomats hostage for 444 days. (Randy Goodman)

1. Worthy steadfastly believed in the free flow of information.

For 41 days in 1956, Worthy reported from China despite a U.S.-imposed travel ban to the Communist nation. While there, Worthy interviewed Chinese leader Chou En-lai. In retaliation for his unauthorized travel, U.S. officials seized his passport upon his return. But that didn’t deter him. Four years later, and without a passport, he made his way into communist Cuba to report on the early days of the Castro regime. When he came back, he was charged and convicted of entering the United States without a passport. A federal appeals court later overturned his conviction, saying the travel restrictions were unconstitutional. Later, he tussled with the FBI and CIA over documents he obtained while reporting on the Iran hostage crisis.

2. He inspired a folk song.

Singer Phil Ochs entered Worthy into the annals of legend on his debut album, All the News That’s Fit to Sing, with “Ballad of William Worthy.” The lyrics go, in part, “William Worthy isn’t worthy to enter our door, went down to Cuba, he’s not American anymore. But somehow it is strange to hear the State Department say, ‘You are living in the free world, in the free world you must stay.’” Listen to the “Ballad of William Worthy.”

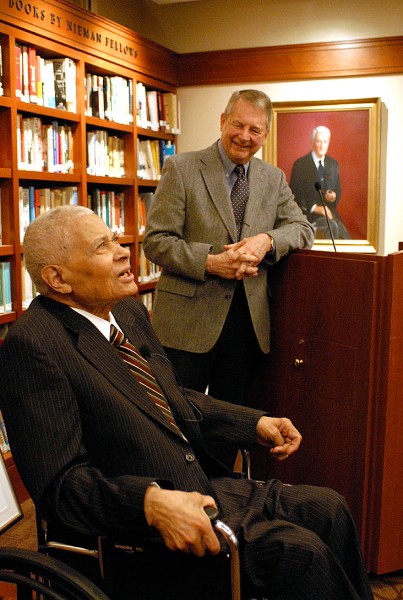

In 2008, William Worthy received the Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism from Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism. At right of Bob Giles, Nieman Foundation curator. (Photo courtesy of the Nieman Foundation)

3. He was red-baited in the U.S. Senate.

In March 1957, the Senate Judiciary Committee held hearings on whether State Department actions had “seriously restricted the travel of American newsmen in foreign countries.” Though McCarthyism and the Red Scare had waned, it was still common for politicians to red-bait, as this exchange between Worthy and Sen. Joseph O’Mahoney, D-Wyo., suggests:

O’Mahoney: May I ask you again, Mr. Worthy, if, in your own consciousness, you are aware of any reason which the State Department might cite for its delay and apparent opposition in issuing your requested passport?

Worthy: No, sir, not at all.

O’Mahoney: You are an American citizen?

Worthy: Right.

O’Mahoney: A loyal American citizen?

Worthy: Right.

O’Mahoney: Has any charge of subversive activity ever been made against you?

Worthy: Not at all.

O’Mahoney: Has any charge of any kind been made against you?

Worthy: No, sir. If you want to make it more specific, if you want to ask me the $64 question, I will be glad to answer it.

O’Mahoney: Well, I don’t want to go into the movies today.

4. He never wavered.

As a Bates student in 1941, he said this after Pearl Harbor: “We must now work to prevent war hysteria and intolerance and to retain civil liberties intact.” At age 84, he was asked if a lifetime of challenging authority had made him weary: “Not weary, but it was not pleasant always to have to defend what you believe in. By temperament, I am not really inclined to get weary.”

5. His anti-imperialist beliefs were forged in the Bates library.

By pure chance, Worthy came across a copy of Scott Nearing’s Dollar Diplomacy, which described how in 1914, U.S. soldiers took $500,000 from Haiti’s national bank and shipped it to New York City for “safe keeping.” This gave the U.S. control over the national bank at a critical time in Haiti’s history. Worthy would later say that learning about that event that day in the library “really, turned me in an anti-imperialist direction, from which I have not veered ever since. It was one of the great shocks of my life, to read that.”

We recommend reading Worthy’s obituaries in the The New York Times and The Washington Post. You can also read a 1995 Bates Magazine feature on Worthy here.