Pursuing the hirsute, Rebecca Herzig explores suffering, feminism and science through hair removal

We like to think that what goes on in our mind is separate from — and better than — mundane things like “changing diapers or removing snow,” Rebecca Herzig told an audience in the Keck Classroom on Dec. 2. “I teach and write against those separations.”

Herzig’s new book, her third, exemplifies that resistance by exploring a topic that is as “corporeal and mundane” as possible: hair and hair removal.

Rebecca Herzig delivers a talk celebrating her appointment as the Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at Bates on Dec. 2. (Sarah Crosby/Bates College)

Plucked: A History of Hair Removal in America will be published by NYU Press in January, and last Tuesday Herzig talked about the book in a lecture marking her appointment as the Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies.

The Johnson Professorship, supported by an endowment from the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation, recognizes a Bates faculty member who has made transformative contributions to interdisciplinary studies.

Herzig’s talk was titled Knowledge Incarnate: Feminism, Science and the Problem of Suffering.

In Herzig’s work, the concept of “suffering” is less a medical or religious term and more a way to explore the human condition in a political sense. Who gets to decide what suffering means? Whose suffering “counts,” and whose suffering becomes just part of the background hum, “like the lights in this room”?

Take the detainees at Guantanamo, said Herzig, who is a historian of science whose research focuses on the relationships between technology, race and gender in the United States.

Everyone knows they were subjected to sleep deprivation and waterboarding, among other acts. Their beards were forcibly shaved, too, an act consistent with definitions of torture, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross. (A form of religious humiliation, forcible beard shaving was also used on Jews by the Nazis.)

But in the U.S., both critics and defenders of what went on at Guantanamo ignored the beard shaving. Herzig pointed to Jill Lepore’s notable 2013 account in The New Yorker, in which the words “beard” and “shaved” aren’t even mentioned, never mind whether the practice was to be condoned or condemned.

Was the advent of genital waxing the ultimate emblem of women’s political freedom?

Herzig asked her audience to compare that utter silence to the noise from commentators in the early 2000s as American women began shaving or waxing their pubic hair. The public “tussle” about genital waxing revealed “contestation over an emerging social norm,” she said.

As commentators tussled with this new norm, some asked if the advent of genital waxing meant that women were, once again, being trapped by sexism or confined by consumerism.

Or, they asked, was the act the ultimate emblem of women’s political freedom — 30 years after Ms. magazine declared that body hair was the “last frontier” of feminist struggle?

As with past hair-removal trends — X-rays, toxic thallium acetate depilatories, or “Velvet Mittens” made from sandpaper, all used in the early 1900s — users felt a sense of power and freedom. But were these feelings derived from using these new techniques or by being able to “reconstitute social norms”?

When it comes to hair removal, there’s a funny phenomenon at play in the United States, Herzig pointed out.

While research shows that people are aware of social norms, Americans always say that their own motivations are based on “self-enhancement or pleasure. They never say it’s to adhere to social norms,” she said. “But, they report that other people remove their hair to conform to social expectations.”

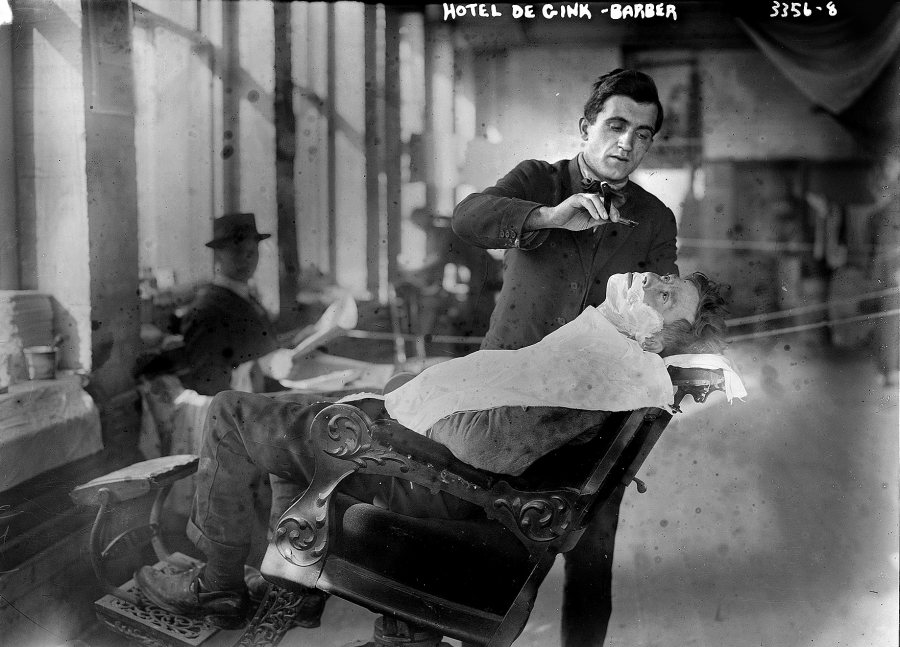

A New York City barber in 1915 shaves a customer at Hotel de Gink, a hotel for the homeless. In her book “Plucked,” Herzig observes that as private bathrooms became the norm for Americans of means in the early 20th century, the activity of men shaving, “done by men on men in public, male spaces” became private and thus “individualized and concealed.” (George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-18192)

Hair removal as a research topic, admitted Herzig in a candid moment, was almost too mundane. As she developed and published her early research, some reviewers deemed it not worthy of academic study.

But Herzig persevered, and her pursuit of the hirsute turned into “a fantastic topic. Hair is the liminal object” — meaning something on a boundary — “par excellence.”

Hair’s importance as a liminal object appears, said Herzig, in how we care for our hair and how we suffer for it, practices that “tend to magnify other processes of political inclusion and exclusion, whether in terms of race, sexuality, nationhood, gender or ability: where you decide the line should be between self and other.”

The decision between inclusion and exclusion, Herzig pointed out, was seen in how some commentators in the 2000s argued that genital waxing was an emblem of freedom, the kind of personal freedom that America should bring to women in Islamic societies.

“With whose blood were my eyes crafted?”

Herzig began her talk by explaining why she resists separating ways of knowing from “ways of living” in the physical world, rejecting the image of the products of our mind as “moving through ethereal space in some transcendental way.”

She quoted a mentor, the scholar Donna Haraway, who offered a famous challenge to anyone daring to claim a certain perspective without knowing the ground beneath them. Writing in 1991, Haraway said that vision is “always a question of the power to see.” And she asked, “With whose blood were my eyes crafted?”

For Herzig, the question becomes “what invisible webs of life and death have enabled my ways of knowing, our ways of knowing?” The question, she said, “buzzes through my mind nearly every day at Bates. Who has made it possible for me to be here? What makes my position possible, whose blood?

“It is a galvanizing question,” she said, “not a source of guilt or shame. It is a call for more study….Learning to reflect on the bloody conditions of my own being and knowing, the violence and injustice, continually returns my attention to life, with all of those unexpected connections and possibilities.”

Herzig’s book Plucked follows 2005’s Suffering for Science: Reason and Sacrifice in Modern America and, in 2009, co-edited, with Evelynn M. Hammonds, The Nature of Difference: Sciences of Race in the United States from Jefferson to Genomics.

Chair of the Program in Women and Gender Studies at Bates, Herzig has won numerous awards for her work, including the college’s Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching.

Herzig received a doctorate in the history and social study of science and technology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a bachelor’s degree in American cultural and environmental studies from the University of California, Santa Cruz.