Frank Glazer, pianist of international renown and longtime Bates artist in residence, dies at age 99

Frank Glazer, a pianist internationally known for his artistry and dedication, beloved for his generosity and celebrated for his artistic longevity, died on Jan. 13 at age 99.

He was a longtime Bates artist in residence and lecturer in music.

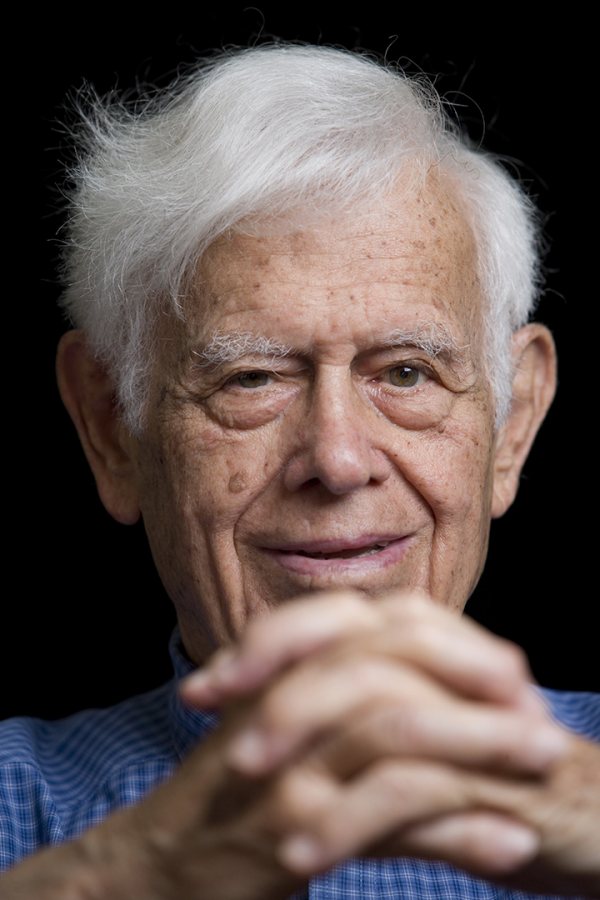

Frank Glazer sits for a portrait on Feb. 8, 2014, at Bates, prior to a piano performance in the Olin Arts Center Concert Hall celebrating his 99th birthday. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Born in Wisconsin on Feb. 19, 1915, Glazer gave his concert debut on a vaudeville stage in Milwaukee in 1927, embarking on a musical career that remained vital and creative until the final weeks of his life.

Glazer’s final public performance was Nov. 7 at Bates, featuring music of Beethoven, Haydn and Schubert. He had hoped to celebrate his 100th birthday in February with special concerts at the college and at the Boston Athenaeum.

Funeral plans have not been announced.

“From the first time I met him, one of the most amazing things that I found about him was his generosity,” former Glazer student Duncan Cumming ’93 said in a 2006 interview.

“There was never a clock with Mr. Glazer.”

Cumming, now a concert pianist and assistant professor of music at the University at Albany, wrote the biography The Fountain of Youth: The Artistry of Frank Glazer. “There was never a clock with Mr. Glazer.”

Virtually any conversation with Glazer glittered with musical lore. He had played vaudeville in his teens; had his own television show during the early 1950s, that medium’s golden age; and, with his wife, Ruth, co-founded a concert series in Maine during the state’s 1970s cultural renaissance.

Frank Glazer, photographed at home in Topsham, Maine, in 2006. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In the 1930s he studied with both Artur Schnabel, a leading interpreter of the Viennese masters, and with Arnold Schoenberg, whose atonal compositions were the antithesis of Viennese lyricism. A champion of contemporary composers, Glazer nonetheless devoted one of his late recordings to the showy salon pieces that were in fashion during his youth.

It was all part of the same life to him, says music department colleague James Parakilas, the college’s Moody Family Professor of Performing Arts. Glazer embodied the continuity of musical life — something particularly valuable for students, to whom, say, American composer Aaron Copland “seems as old as Bach,” Parakilas says. “Frank knew Aaron Copland. That allowed him to put things in perspective.”

“We are dealt a certain hand. But we have a lot to say about how we play the game.”

Glazer received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from Bates in 2011 honoring “the faithfulness he has shown to the demands and to the beauty of his art” and recognizing “a musician who has reconciled the single-minded pursuit of excellence with the generosity and empathy of a teacher eager to share the fulfillment you have found.”

“I believe it serves no useful purpose to compare oneself with another person. Each of us is unique,” Glazer told the Class of 2011. “We are dealt a certain hand at birth over which we have no control. But we have a lot to say about how we play the game.”

Glazer made his New York City debut in 1936 at Town Hall, and his orchestral debut as soloist three years later with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Koussevitzky. His career hit its stride in the 1940s after a two-year effort to reinvent his piano technique. This study produced a relaxed, economical style central to both Glazer’s artistry and his astonishing musical longevity in a field where hand problems are endemic.

“I don’t know what retirement means,” Frank Glazer often said. “I’ve worked all my life to get to this point, where I like the sounds I hear.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Glazer began teaching at the Eastman School of Music in 1965, and in 1977 came to Bates, where he became an artist in residence in 1980.

Over the course of long career, he played countless solo, chamber ensemble and orchestral concerts; composed music; made more than 60 recordings, including two released by Bates in 2010; hosted his own television program in the 1950s; and, in Maine, co-founded the New England Piano Quartette and the Saco River Music Festival.

Parakilas said in 2006 that “music has a power in Frank’s life that he wants to let other people in on. And it’s the same whether they’re in the audience, or having a lesson, or in a class that he’s addressing. It’s always there.”

Last November, Glazer himself told Tom Porter of Maine Public Radio that “like an actor studying Hamlet or Macbeth, the older you get and more you do it, the more you see in it, and you wonder why you didn’t see that last time, or five years ago.”

“I don’t know what retirement means,” Glazer often said. “I’ve worked all my life to get to this point, where I like the sounds I hear.”