MLK Day keynote: Black Lives Matter movement is a sign of hope

Peniel Joseph, Tufts University historian and author, delivers Bates’ 2015 MLK Day keynote address. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

What does the Black Lives Matter movement really want?

Yes, it’s one of those questions that can be driven more by hostility than curiosity. Still, in his keynote address during Martin Luther King Jr. Day observances at Bates on Jan. 19, historian Peniel Joseph had an answer ready.

“What they want is a new New Deal. They want a greater Great Society,” said Joseph, a professor at Tufts, author and authority on the Black Power movement. “They want an expansive vision of social, economic and political justice that connects democratic ideals to democratic reality.”

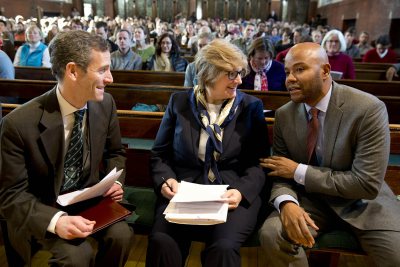

From left, Bates Dean of the Faculty Matt Auer, President Clayton Spencer and Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote speaker Peniel Joseph have a word as the event begins. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The divorce of ideals from reality was central to the talk, titled Reimagining Martin Luther King Jr. in the Age of Obama and the Age of Ferguson, that an energetic Joseph offered in the Peter J. Gomes Chapel.

Joseph described a mythologized King, the “prince of peace” that for many has supplanted the reality of King’s last years, when his increasingly radical views made even some fellow black leaders uncomfortable. Joseph also outlined the current resurgence of institutionalized racism in a more insidious form that avoids the language of prejudice while serving its goals.

Against this context, Joseph suggested that the Black Lives Matter movement is a sign of hope — for defenders of both social justice and, in fact, democracy itself — because it supports idealism with effective activism.

In her welcome to a capacity crowd at the Chapel, Bates President Clayton Spencer was pleased to point out that the college’s MLK Day committee had picked the day’s theme — From Selma to Ferguson: 50 Years of Nonviolent Dissent — in September, prior to the grand jury decisions about the police shootings in Ferguson and New York City that elevated outrage to a new level.

The Gomes Chapel audience during the 2015 MLK Day keynote address by Tufts University historian and author Peniel Joseph. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Anticipating Joseph, Spencer said that Bates’ choice of theme “shows that we on this campus were prepared to challenge ourselves to acknowledge and act on the ongoing stark gap, nearly five decades after the death of Martin Luther King, between the depth of our ideals as a society and our lived reality.”

Bates people have been prepared for that challenge for decades, she said, pointing the important legal victories for civil rights won during the mid-20th century by John P. Davis ’25 and James Nabrit ’52.

Son of a union member who first took him out on a picket line when he was 8 years old, Joseph said, “I come to activism from a real-world point of view.” He provided both historical and moral context for the day’s programming at Bates.

Joseph devoted much of his talk to a whirlwind review of signal events in the civil rights movement from 1954 to 1965, as King became the leading voice of the movement. These years, which Joseph called the “heroic period” of the movement, began with the U.S. Supreme Court finding that school segregation is unconstitutional in Brown vs. Board of Education; and ended with a year marked with the marches on Selma, the passage of the Voting Rights Act and the Watts riots.

If these events were news to many younger listeners in the Gomes Chapel, what came next may have been ear-opening to some older folks as well. Joseph pointed out that during the last three years of his life, King became increasingly radicalized, coming out in opposition to the war in Vietnam and in favor of a guaranteed income for impoverished Americans.

Marcus Bruce, Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies, and Associate Dean of Students James Reese listen to the MLK Day keynote address. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“We need to be willing to speak truth to power, no matter the cost,” King said, and the cost to him was losing access to the political establishment. “There [were] no more massive standing ovations by the mainstream for Dr. King in 1966, ’67 and ’68,” Joseph said.

In Chicago, even black leaders — fearing the loss of such patronage as was available to them from Mayor Richard J. Daley’s benighted political machine — told King he had gone too far.

Today, Joseph said, it’s not uncommon to point to Barack Obama’s presidency as a symbol of how far civil rights have advanced in the U.S. And yet, “the reality that we live in is a much, much, much more complex reality,” Joseph said.

If recent events in Ferguson, Staten Island and Cleveland — where a 12-year-old African America boy carrying a toy gun was killed by police — are high-profile examples of institutionalized racism, Joseph pointed out that conditions for African Americans have gone backward in more deep-seated ways as well, from school segregation to incarceration rates to unemployment and poverty.

Many black children, Joseph pointed out, have their first experience with the criminal justice system when they are arrested in school — as young as age 5 or 6.

“We had a better conversation about race and racism in 1965 than we do now,” Joseph said. “At least in 1965, we admitted that there were structures of racism and racial segregation.” Now our society practices a sort of “color-blind racism,” he said, where laws and policies achieve racist ends while never explicitly mentioning race.

John Smedley, Tim Clough and Dale Chapman — aka the Three Point Trio — opened the King Day keynote event with jazz. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“Even as we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr.,” Joseph said, “we divorce King the icon from King the political activist who’s willing to speak truth to power and who said that ‘injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’

“We celebrate the dreamer, but we divorce the dreamer from the actual dream.”

The emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Joseph said, shows that the time may not be past, after all, for realizing the dream.

“The most important, and really hopeful and optimistic, aspect that we’re left with, when you think about ‘from Selma to Ferguson,’ is the fact that so many young people, like in the 1960s, are actually not just demonstrating and protesting — they are organizing.

“They are organizing on behalf of social, political, economic and racial justice. And they are organizing to try to fill that gap between democracy as an ideal in America, and democracy as an actual living, breathing fact.”