What we owe genocide survivors

Alex Dauge-Roth, associate professor of French and francophone studies, gives the Kroepsch Lecture on March 18, 2015. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

What shapes a meaningful conversation with people whose sense of self has been fractured by witnessing the horrors of genocide? In such conversations, who controls what is meaningful and worthy of discussion, remembrance and action?

Alexandre Dauge-Roth, recipient of Bates’ 2015 Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching, devoted his Kroepsch lecture on March 18 to a thorough analysis of those questions — specifically as they pertain to his decade of engaging Bates students with survivors and their stories of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

And whether or not he ever used the words “power” and “ownership” during his late-afternoon lecture, those concepts were the floor his talk stood on.

How do power relationships play out in the dialogue between a trauma survivor and that person’s interlocutor? Who owns the survivor’s story, the space in which it’s heard and its retellings? Most important, what is the interlocutor’s ethical and civic obligation to the survivor?

Associate professor in French and francophone studies, Dauge-Roth is internationally known for his research into personal narratives from the genocide, work represented by his 2010 book, Writing and Filming the Genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda: Dismembering and Remembering Traumatic History (Lexington Books).

Dozens of students, colleagues and friends offered a warm welcome to this scholar and teacher who, in his 10th year at Bates, “received many, many nominations for the Kroepsch,” as Dean of the Faculty Matt Auer said in introducing Dauge-Roth.

Recipients of the award are nominated by current students and recent graduates, and the honoree is selected by a panel of recent recipients. Auer quoted a nominator who had taken part in Dauge-Roth’s Short Term course in Rwanda. That person praised Dauge-Roth for teaching not only academic aspects of the genocide, but the “importance of being understanding, nonjudgmental and sensitive with the [Rwandans] we worked with.” (Another nominator drew laughter by calling Dauge-Roth “the thesis adviser I needed, not the thesis adviser I deserved.”)

Dauge-Roth’s talk was titled The Transformative Power of Literary and Testimonial Encounters. Revealing a mentality scrupulous in both its morality and its attention to the ramifications of an idea, the hour-long talk traced an arc from Dauge-Roth’s own studies, in his native Switzerland and at the University of Michigan, to the thinking behind signature courses that he introduced at Bates.

Both courses, “Documenting the Genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda” and “Learning with the Orphans of the Genocide in Rwanda,” were driven by interaction between Dauge-Roth’s students and genocide survivors. The latter, a Short Term unit, has twice brought students to Rwanda.

Together, Sarah Bravmann ’12 and Alexis Mutimukunda face a genocide exhibit of human skulls at the Ntarama Memorial in Rwanda during the Short Term course “Learning with Orphans of the Genocide in Rwanda” in 2009 led by Alex Dauge-Roth, associate professor of French and francophone studies.

As he designed these courses, he recounted, a central issue quickly emerged. “What are the informative — but more importantly the potentially transformative — places, voices and roles, that we as an academic community are willing to offer to members of another community whose history we are studying?”

“My hope was that a polyvocal and decentered mode of teaching would open up challenging spaces of dialogue, inviting students to re-evaluate the borders of academia; to reflect on their civic role when exposed to histories of pain; and to question the understanding, circulation and production of knowledge about others.”

Inspired by research conducted for his graduate degrees, notably his work at Michigan with the personal testimony of people living with AIDS in France, Dauge-Roth focused on the literature of survivors of the genocide — biographies, diaries, oral history and film.

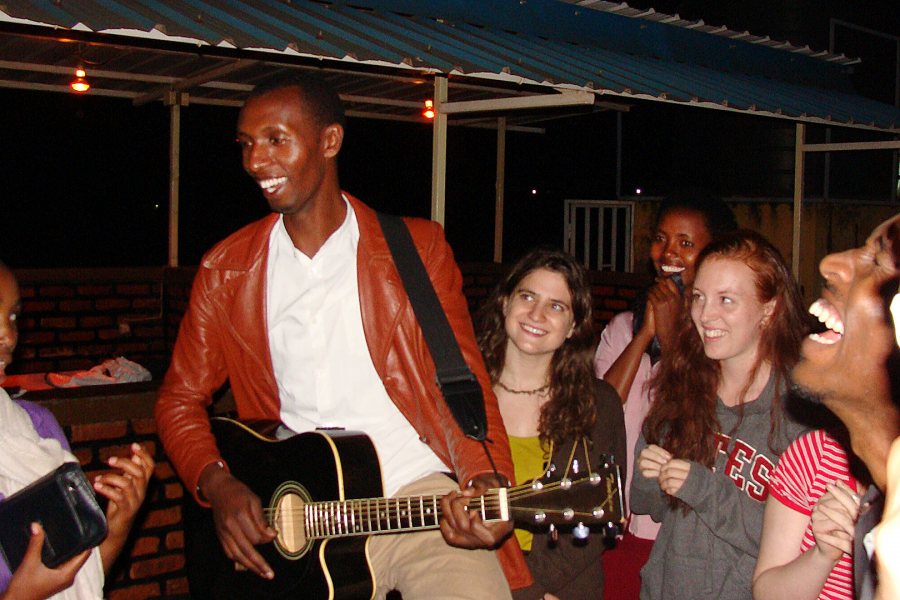

“Interactions with survivors of genocide is not only about the past and grievance but also about sharing laughter within the present despite of it all,” says Dauge-Roth. Here, Bates students and survivors of the genocide in Rwanda gather for music and fellowship during Short Term in 2013. The survivors live at Tubeho, a collective of houses in Kigali where orphans of the genocide live in reconstituted families.

It was his dissertation director at Michigan, Professor of Comparative Literature Ross Chambers, who articulated the idea that reading survivors’ literature can’t be a passive act: Listeners, Dauge-Roth learned, need to “develop a critical self-awareness regarding their own agency and inadequacy as they respond to survivors’ stories.”

As he created his Rwanda-based courses for Bates, Dauge-Roth drew on three consequential lessons from his graduate work. First, trauma causes what he calls a “fracture within the self,” a break between one’s pre- and post-trauma selves that must be negotiated.

Second, that negotiation is not just personal and internal, but social and cultural. Traumas such as AIDS or the Rwandan genocide become, or reflect, social preoccupations. So society dictates the terms of the discourse around them — often to the detriment of the traumatized, as in the bleak early years of the AIDS crisis, when sufferers were branded as “social parasites.”

“Third, I learned that testimonial literature forces on us a political discussion about the social representation of suffering and our civic role in its unfolding and aftermath,” Dauge-Roth said. Crucially, in the words of literature professor Antoine Compagnon, “what is at stake for us as readers is our willingness to be disturbed by, and ultimately transformed by, our encounter with another’s experience.”

In the audience at Alex Dauge-Roth’s Kroepsch Lecture were, from left, departmental colleague Kirk Read; Katherine Dauge-Roth, Alex’s wife; and their son, Aymeric Dauge-Roth. (Phyllis Graber-Jensen/Bates College)

As Dauge-Roth said in describing the Short Term course in Rwanda, his hope was to create “a space of encounter that would allow survivors to bear witness, on their own terms, and challenge us, their interlocutors, to explore what it means to be a listening community; and what responses we must forge as their painful histories are passed on to us.”

So what does it take to be a listening community? Dauge-Roth offered three tenets (“I’m French — everything goes by threes,” he joked). First, it requires that we move past pity and compassion, “since these are just part of the strategy for maintaining the status quo.” Second, it means incorporating into our own histories the history of pain that we encounter.

Third, it means that listeners “see themselves as indirect witnesses, whose responsibility is to develop a critical self-awareness regarding their own agency and inadequacy as they respond to survivors’ stories. Learning with the survivors” — not merely from; a key distinction for Dauge-Roth — becomes an “ethical gesture” that makes possible reciprocal relationships between survivors’ histories and our own.

“These courses have taught me and my students,” he concluded, “that listening to testimonies bearing witness to the genocide questions both our willingness to confront disconcerting human behaviors and our sense of cultural hospitality — when hospitality is understood as a transformative interruption of one’s self.”

“Facing the disturbing experience of genocide demands that we identify what role we play, and ought to play differently, in the social recognition and circulation of the histories of pain that community partners share.”

View a video of Alex Dauge-Roth’s Kroepsch Lecture: