Campus Construction Update: May 19, 2015

With a piece of structural steel in the foreground awaiting its ride in the sky, the skeleton of the 65 Campus Ave. student residence is shown on May 13, 2015. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Getting here from there (updated May 28!): Bates-bound motorists, watch for full closures of Campus Avenue the weeks of June 1 and June 8.

- June 2 and 3, Campus will be closed between Bardwell and Franklin streets;

- June 4 and 5, from Franklin to Central Avenue;

- and June 8 and 9 from Franklin right into the Central Avenue intersection. But note that a lane from Franklin across Campus into the Chase Hall service road will be open throughout.

You’ll be directed to a Vale Street detour while these two blocks of Campus undergo surgery to make sewerage connections. See a diagram of the closures.

Uprights in place on the first day of placing steel at 65 Campus Ave., April 22, 2015. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

We’ll steel away: It’s just shy of a month since the steel started rising for Bates College’s new student residence at 65 Campus Ave. But already the shape and, more intriguingly, the size of the building are fully discernible.

The steel skeleton is the full four stories high. The roof structure started appearing on May 11 and was nearly done by the 19th. Most of the shiny corrugated metal decking that will support the concrete floors is in place.

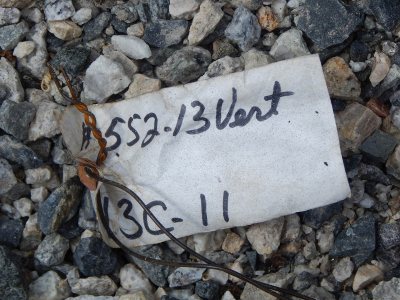

A rigger for Stellar Steel looks for the next piece of the 65 Campus Ave. metal to give to the crane on April 22, 2015. Note the markings on the components that specify where and in what order they will be placed. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

So at this point it doesn’t take too much imagination to picture the transformation that’s coming to Bates’ south side as No. 65 and its fraternal twin at No. 55 near completion, more than a year from now. And that mental picture will be even easier to conjure up come June, when steel starts rising for 55 Campus.

Construction manager Consigli Construction and its subcontractors have made good progress since work in the field began, nearly a year ago — but it hasn’t always seemed like it, between a heavy winter, the green fences that block views of the construction and the fact that until mid-April, much of the work happened below grade.

The label on a piece of steel indicates where in the 65 Campus Ave. structure it will be placed, and when. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

But now the job is flying along, literally and metaphorically. “I’ve been very pleased,” says Chris Streifel, who manages the construction project for Bates. The steelwork at No. 65 “has been a well-orchestrated process, from the structural design to the fabricators’ design to the final approvals.”

Everyone has “worked diligently and thoroughly. And the result is that it’s been a fairly trouble-free installation. It doesn’t always work as smoothly in the field as this has.”

Erectors at work on April 22, 2015, the first day of hanging steel at the 65 Campus Ave. student residence. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

It’s always pleasant to watch other people work (especially when watching them is your work). But watching Stellar Steel Erectors of West Suffield, Conn., hang metal is flat-out compelling, between the aerial ballet of the steel dangling from the crane and the seeming ease with which the skeleton has gone together.

The state of the steel at 65 Campus Ave. on May 7, 2015, seen from Central Avenue and the official Campus Construction Update ladder. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Stellar’s crew at Bates is a mere eight or nine workers. Up on the building, the people who are actually grabbing the steel out of the air and fastening it into place are called erectors.

On the ground is the rigger, who coordinates the work. He and an assistant called a flagger arrange the steel in a sensible order on the ground as it arrives from fabricator Norgate Metal. The rigger directs the erectors and the crane operator and keeps the steel pieces, marked accordingly by Norgate, floating up in the proper order.

The Link-Belt crane can lift 40,000 pounds to a height of 300 feet. The crane operator, with some radio guidance and hand signals from colleagues, places all of the steel solely by eye — no GPS or GoPro helping out.

The student residence at 65 Campus Ave. has entered its third week of steel placement in this image taken May 7, 2015. Notice the second-floor welding at right. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Making every lift count, the rigger will often attach to the crane’s cables as many as three steel components — and no more than three, according to OSHA regulation — making what insiders call a “Christmas tree.”

Campus Construction Update admires the metal’s tasteful palette of pale gray and dull maroon (sorry, Bobcats: not quite garnet), but in fact there’s a reason the colors vary.

With gray conduits for electrical, telecom and data service in the foreground, workers build a form for concrete footings at 55 Campus Ave. on May 7, 2015. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Some steel components will later be coated with paint. Others will take fire-resistant coatings, such as a thick textured spray-on goop or so-called intumescent paint, which, in the unlikely event of a fire, help keep the steel below the temperature — upwards of 800 degrees Fahrenheit — at which it starts to droop.

Different coatings require different primers, and the different primers come in different colors, says Consigli project engineer Kirk Mullen.

Concrete mixers ready to place foundation footings for the 55 Campus Ave. student residence on May 7, 2015. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Tim Schneider, Consigli project manager, explains that every joint in the steel skeleton has been designed by an engineer. Some joints are welded, typically when necessary for structural rigidity or in areas where a nut and bolt can’t physically fit. External inspectors make sure the welds are done right.

Most joints, though, are fastened with good old nuts and bolts — albeit much beefier than the ones that your Dad kept in old Sanka jars on the shelves above the workbench. These nut-and-bolt connections each need to be tightened to a specified tension.

With a “Christmas tree” — multiple pieces of steel in one lift — dangling from the crane, the framework of 65 Campus Ave. is shown from the west on May 13, 2015. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Back in the day, the prevailing “turn of the nut” method involved some math, so-called match-marks and a couple of loving caresses with a big wrench to attain the proper tightness. But today’s fasteners, like technology in so many other areas, tell you whether you’re doing it right.

So-called tension control bolts, or TCBs, come with a sacrificial part that breaks off when the desired tension is reached. (Pencils serve a similar role here in the Campus Construction Update penthouse when the big wrench of deadline pressure is applied.)

A tension-control bolt, with nut. As the fastening is tightened, the ribbed piece at right snaps off the bolt when the proper tension is reached. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

TCBs make visual inspections fast and straightforward, Schneider says. Streifel adds that “the TCBs themselves are tested on site to make sure they snap off at the right tension. And the guns they tighten them up with are calibrated to make sure they’re applying the right torque. So there’s a lot of checking and double-checking.”

Speaking of which, in a final step, the erectors periodically true up their latest work and only then finalize the fastenings. “Steel isn’t perfect — it’s got some bends and waves in it,” Streifel explains. “Each crew has their own technique, but usually you’ll put portions of a structure together loosely just to make sure it all fits.

“For example, when you need to put a crosspiece in between two other pieces, you might have to push them apart a little bit to get it in. And if you’ve bolted everything up rigidly, you’ve lost your flexibility to do that.”

With this phase of the Campus Life project now ahead of schedule, Streifel expects Stellar to move crew and crane across Franklin Street in two or three weeks.

“All other things being equal,” he says, “the steel should go slightly faster at 55 Campus Ave. The building is a little bit smaller, and without a basement it’s less complicated than 65.

“And you always get the benefit when you’ve done something before that you’re going to go faster the second time.”

Can we talk? Campus Construction Update welcomes your questions and comments about current, past and future construction at Bates. Write to dhubley@bates.edu, putting “Campus Construction” or “What did those pencils ever do to you?” in the subject line. Or use the 21st-century commenting system below.